The most notable aspects of <sage .ai> case are:

- Dealing in domain names in the secondary market is a legitimate trading activity.

- By its very nature, domain name investing is speculative. A domainer usually has the intention of reselling domain names at a price in excess of the purchase price.

- Being a domainer is a risky business and is not always profitable, but trying to make a profit by reselling domain names is not bad faith per se.

Continue reading here

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 3.37), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from experts. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Sage .ai: No Obligation for Investor to Conduct Search For Dictionary Term

(sage .ai *with commentary)

‣ Million Dollar Domain Name: Respondent Did Not and Could Not Have Known of Complainant’s WhatsApp Group (stable .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel Would Have Awarded Damages and Costs Against University of Montreal (extenso .org *with commentary)

‣ The Domain Name Composed of Descriptive Term (thecareergirl .org *with commentary)

‣ Typosquatting Attempt by the Registrant (bollorelogistic .us *with commentary)

—–

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

The ICA will attend the Domain Days Dubai meeting Nov 1-2, 2023. This is one-of-a-kind event in the MENA region’s domain industry. The conference brings together a diverse crowd of Domain Investors, Registrars, Registries, Monetization & Traffic, Web 3.0 Domains, Hosting & Cloud Providers, SaaS providers, and Industry Enthusiasts.

Kamila Sekiewicz, Zak Muscovitch, and Ankur Raheja will be representing the ICA. We’d love to meet with any members of our UDRP Digest community attending, so please get in touch if you have plans to be there.

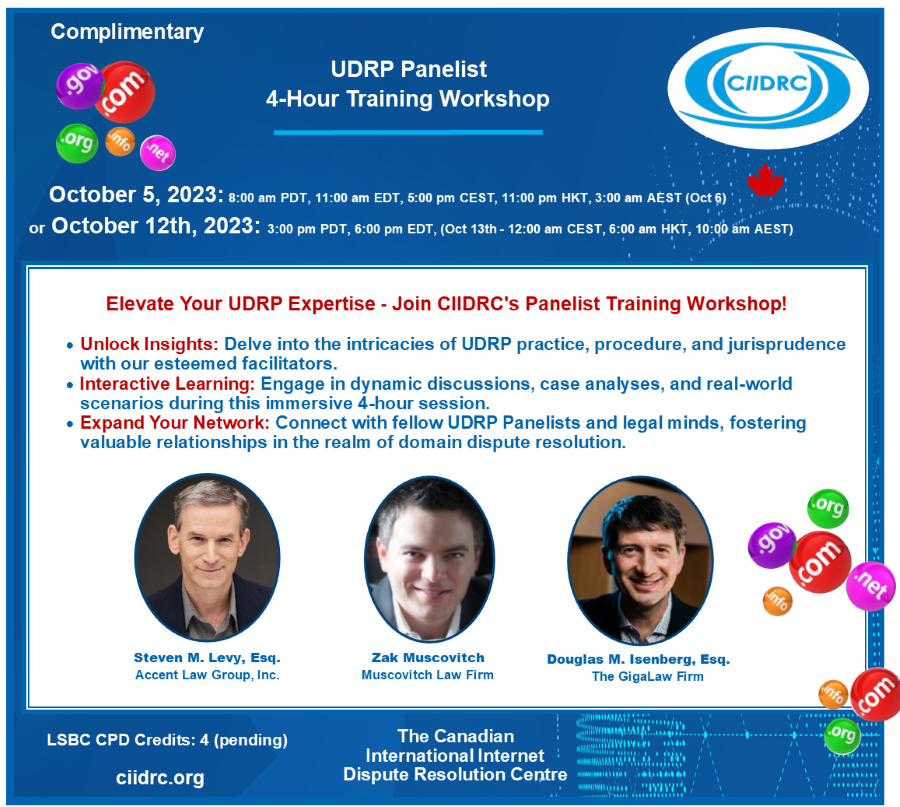

UDRP Workshop registration:

For October 5, 2023 – register here

For October 12, 2023 – register here

Sage .ai: No Obligation for Investor to Conduct Search For Dictionary Term

Sage Global Services Limited v. Narendra Ghimire, Deep Vision Architects, WIPO Case No. DAI2023-0010

<sage .ai>

Panelist: Mr. John Swinson, Mr. W. Scott Blackmer, and Mr. Tony Willoughby

Brief Facts: The UK Complainant, founded in the early 1980s, is a well-known provider of technology solutions for businesses. The Complainant owns various trademark registrations for SAGE, which includes UK registration (August 23, 1991), and US registration (April 20, 1999). The US Respondent has been a domain name investor since 2013, who buys and holds domain names for resale. The Respondent purchased the disputed Domain Name from a previous registrant Sage Health on January 8, 2018 and resolves to a page that lists the domain name for sale. The disputed Domain Name has also been listed on the GoDaddy platform for sale as well as requesting minimum offers, such as USD $179,888.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent must have been aware of the existence of the Complainant’s SAGE trademark; that the Respondent opportunistically registered the SAGE trademark in the “.ai” ccTLD space knowing that the Complainant was a technology company where artificial intelligence (“AI”) is of core importance to the Complainant; and that the excessive price at which the disputed Domain Name is listed for sale is evidence of knowledge of the Complainant. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent has passively held the disputed Domain Name and has made no use of the disputed Domain Name for over 5 years and that this passive holding constitutes bad faith under Telstra Corporation Limited v. Nuclear Marshmallows, WIPO Case No. D2000-0030.

The Respondent has been a respondent in two prior decisions under the Policy, it prevailed in <amadeus .co> case, while it was unsuccessful in <virtuoso .io> case. The latter is the subject of a pending U.S. Federal Court action filed by the Respondent. The Respondent contends that SAGE is a well-known dictionary term and is used by 1,648 businesses in their registered trademarks and by 34,574 businesses as their company names; and that there is no evidence that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name primarily for the purpose of selling the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant. The Respondent produces a declaration under penalty of perjury that he had never heard of the Complainant prior to the filing of the Complaint.

Held: The Complainant submits that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name primarily for the purpose of opportunistically selling the disputed Domain Name to the Complainant. The evidence does not support this claim. Dealing with domain names in the secondary market is a legitimate trading activity. By its very nature, it is speculative. A domainer usually has the intention of reselling domain names at a price in excess of the purchase price. Some domain names sell, and some sit on the shelf unsold. Being a domainer is a risky business and is not always profitable, but trying to make a profit by reselling domain names is not bad faith per se.

The Respondent provided a signed declaration stating that he never heard of the Complainant prior to the filing of this Complaint and bought the domain name because it is a single-word generic term and believed that the domain name would appreciate in value. The Panel considers that this is not a case where an obligation to conduct searches should be imposed on the Respondent because “sage” is a dictionary term. Even if the Respondent had been aware of the Complainant’s trademark rights, this knowledge would not have necessarily prevented the Respondent from acquiring the disputed Domain Name in good faith for its common meaning, so long as the disputed Domain Name is not used by the Respondent in a manner that infringes upon the Complainant’s trademark rights.

The Complainant further asserts that the “excessive price” at which the disputed Domain Name was offered for sale is an obvious sign of bad faith on the side of the Respondent. The Panel disagrees. Moreover, the Telstra case is long-standing but relatively narrow in operation. Lastly, the Amadeus case (where the Respondent was successful) and the Virtuoso case (where the Respondent was unsuccessful) do not, themselves, demonstrate a pattern of cybersquatting by the Respondent – who has been in the domain name investment business for ten years. Of course, losing in a prior UDRP or court case would not mean one is always in bad faith and prevailing in a prior UDRP or court case does not immunize a respondent from a bad faith finding in a later case, as the facts of each case must be considered on their own.

Accordingly, the Panel concludes that the Respondent did not register the disputed Domain Name knowing of or because of the Complainant or its trademark rights.

Concurring opinion 1 (Mr. W. Scott Blackmer):

I concur with the Panel Decision to deny the Complaint. I remain skeptical of the Respondent’s denial of prior awareness of the Complainant, given the Respondent’s history of registering domain names identical to established or trending technology trademarks comprised of dictionary terms (as noted by this Panelist in the Virtuoso case and by the dissenting panelist in the Amadeus case). However, the Complainant bears the burden of furnishing persuasive evidence of trademark targeting and failed to demonstrate that the mark was well known in the United States and likely to be known to the Respondent at the time the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name. This was important to reliably infer bad faith, given the nature of the mark and the Respondent’s denial.

Concurring opinion 2 (Mr. Tony Willoughby):

I agree with my colleagues that the Complaint must fail. I also agree that in light of the finding under the third element, it may strictly be unnecessary to consider the second element. However, I take the view that the Respondent is entitled to a positive finding that possibly he has a right and certainly a legitimate interest in respect of the disputed Domain Name. There is no dispute between us that the name dealing is a legitimate activity. The Respondent purchased the disputed Domain Name from a legitimate source and there is no evidence that the Respondent has made any use of it save to advertise it for sale, a legitimate use in the context of a legitimate form of business.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Paula Barnola, Spain

Respondents’ Counsel: Greenberg & Lieberman, United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

I am reluctant to comment upon this case because the Panelists’ own findings and comments (both in the main decision and in both concurring opinions) speak remarkably well for themselves. This Panel deserves particular credit for laying out its reasoning and findings so well. Perhaps it is nevertheless of some utility to list out what I saw as the most notable aspects of this case:

- Dealing in domain names in the secondary market is a legitimate trading activity. However where the case circumstances point to a speculative registration for the specific purpose of targeting existing brand owners, this runs afoul of good faith.

- By its very nature, domain name investing is speculative. A domainer usually has the intention of reselling domain names at a price in excess of the purchase price. Some domain names sell, and some sit on the shelf unsold. Being a domainer is a risky business and is not always profitable, but trying to make a profit by reselling domain names is not bad faith per se.

- The Complainant did not provide evidence to show that its SAGE trademark is so well known that a person in the position of the Respondent must have heard of it.

- If searches would have produced results showing that a term is a dictionary term, it may not be a case where an obligation to conduct searches should be imposed on the Respondent.

- Even if the Respondent had been aware of the Complainant’s trademark rights, this knowledge would not have necessarily prevented the Respondent from acquiring the disputed domain name in good faith for its common meaning.

- Knowledge of the existence of a trademark is of no help to the trademark owner unless the domainer is making a use of it indicating that the trademark or its owner is being targeted.

- On the evidence, the Panel is not in a position to opine of the sale price.

- If the disputed domain name is registered without knowledge of the Complainant and in good faith, then setting a high price once becoming aware of the Complainant is not of itself contrary to the Policy.

- Merely asserting that the Complainant has a trademark and that the Respondent has not used the disputed domain name is typically not sufficient to satisfy the Telstra test. The Telstra case is long standing but relatively narrow in operation.

I now cannot resist however, highlighting a point made by Panelist Tony Willoughby in his concurring opinion, which I have been trying to make for some time, but less convincingly. As the Panelist notes in his concurring opinion, the WIPO Overview states that, “Panels have recognized that merely registering a domain name comprised of a dictionary word or phrase does not by itself automatically confer rights or legitimate interests on the respondent; panels have held that mere arguments that a domain name corresponds to a dictionary term/phrase will not necessarily suffice”. [emphasis added]. The Panelist further notes that, “if the use of the domain name is consistent with the dictionary meaning of the word, it is likely to give rise to a legitimate interest; if on the other hand it does not do so, but targets the complainant’s trade mark, it does not do so”, but the Panelist asks; “But what about an innocent legitimate use which does not relate to the dictionary meaning of the word, and does not target the complainant’s trade mark?” [emphasis added]

The Panelist sees “no reason in principle why a registrant such as the Respondent, trading in domain names, of itself an unobjectionable activity, should not acquire at the very least a legitimate interest in respect of a domain name comprising a dictionary word and offering it for sale at any price he/she chooses, provided that when registering or acquiring the domain name in dispute he/she has no intention of targeting the complainant’s trade mark.” Indeed.

As I noted in Digest Volume 2.49, when we look at the case law and the consensus that has developed around this issue of rights and legitimate interests in domain names, we see that contrary to the Overview, it has been long-held that where a domain name is a dictionary word, the first person to register it in good faith is entitled to the domain name and this is considered a “legitimate interest” (See for example: CRS Technology Corporation v. CondeNet (Concierge.com) NAF FA0002000093547) and Target Brands, Inc. v. Eastwind Group (FA0405000267475) (Target.com). Furthermore, it has long been held that speculating in and trading in domain names can in and of itself, constitute a legitimate interest under the Policy (See; Audiopoint, Inc. v. eCorp, D2001-0509 and also see, Havanna S.A. v. Brendhan Hight, Mdnh Inc., WIPO Case No. D2010-1652).

As I also noted in Volume 2.49, there is in fact no requirement that a Respondent use or demonstrably prepare to use a domain name corresponding to a dictionary word in order for the Respondent to have a right or legitimate interest in it. Of course, if a domain name corresponding to a dictionary word was registered and used in bad faith, that will likely also mean that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interest in it. But as in the present case and as noted by Panelist Willoughby, it is possible for the Respondent to have a legitimate interest in the dictionary-word disputed Domain Name without having ever used it, let alone to sell herbs – merely as a result of purchasing it in the first place for investment. Panelist Willoughby expressly states that he does not accept the argument that “because the Respondent is not using the disputed domain name for a use based on the dictionary meaning of “sage”, the Respondent cannot have a legitimate interest in respect of it”, and believes that this argument is misconceived. I could not agree more.

This relates to another point which I have tried to make for some time, with similarly limited success; Panelists should not omit making affirmative findings of legitimate interest where the facts so warrant. I am therefore grateful to see that Panelist Willoughby noted in his concurring opinion that he would have conferred legitimate interest in this case. As I explained in Digest Volume 2.37 (in my comment on the RedGrass .com case):

“We see Panels skipping a Respondent’s legitimate interest in many cases. This is often done for reasons of judicial economy, as strictly speaking a case can be dismissed on one prong of the three-part test and therefore the decision need not address any additional, extraneous grounds. Nevertheless, there is a compelling argument to be made that Panelists owe it to Respondents in some cases, to make affirmative findings of their rights and legitimate interests.

This is so for a couple of reasons. First, a Respondent who has had its bona fides challenged and been falsely accused of what essentially amounts to a type of fraud, will often want some vindication and confirmation that indeed the disputed property belongs to them. Though strictly speaking a Panel need not make such a finding and may simply dismiss a Complaint, justice may dictate at least in some cases, that a Panel provide some satisfaction to the Respondent. Second, if Panels were to consistently skip over affirmative findings of legitimate interest in favour of respondents, it has a deleterious effect on bona fide registrants, particularly investors. Their business of lawfully investing in domain names is given short shrift, but more importantly, the case law is thereby not permitted to as fully embrace their bona fide business as it might otherwise be if panelists acknowledged a Respondent’s rights and legitimate interests more often and where appropriate.

Lastly and of perhaps the greatest significance, is that the Policy itself pursuant to Paragraph 15(c), expressly enables a Respondent to “prove” its rights and legitimate interests and implicitly directs a Panel to make such a finding if so proven:

“How to Demonstrate Your Rights to and Legitimate Interests in the Domain Name in Responding to a Complaint. When you receive a complaint, you should refer to Paragraph 5 of the Rules of Procedure in determining how your response should be prepared. Any of the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation, if found by the Panel to be proved based on its evaluation of all evidence presented, shall demonstrate your rights or legitimate interests to the domain name for purposes of Paragraph 4(a)(ii):…” [emphasis added]

Accordingly, if a registrant can have a right and legitimate interest in, for example, a dictionary domain name, without any obligation to use it in connection with its descriptive meaning – as we know to be the case – then Panelists can and should say so.

I also want to highlight a principle from Panelist Willoughby’s concurring opinion which was adopted by the entire Panel to its credit, in its rejection of imposing an obligation to search in the circumstances:

“While some Panels take the view that domainers should conduct trade mark searches in respect of the names they register/acquire, such a view cannot sensibly apply to dictionary words in respect of which there are necessarily innocent, unobjectionable uses of the word/name irrespective of any trade mark registrations which may appear from the search.”

In other words, what’s the point of conducting a trademark search for a domain name corresponding to the common dictionary word, “Lions” or “Blue”? No doubt someone, somewhere has a trademark for that term, and likely many such trademarks exist. If a prospective registrant came across one or many of these marks, should the prospective registrant stop in its tracks and decline to register the domain name? This would of course be foolish since the domain name is fully capable of innocent, unobjectionable use irrespective of such trademark registrations – and importantly, even if the prospective registrant is fully aware of them before registration. They key to bad faith, as always, is targeting, not correspondence to a trademark.

Lastly, in these Digest comments I have repeatedly exhorted Panelists to enforce the appropriate onus of a Complainant having to prove its case and to rely on evidence instead of inclination. Panelist Blackmer to his credit, did exactly that in his concurring opinion where he indicated that although he “remained skeptical of the Respondent’s denial of prior awareness given the Respondent’s history of registering domain names identical to established or trending technology trademarks comprised of dictionary terms”, it is nevertheless “the Complainant [who] bears the burden of furnishing persuasive evidence of trademark targeting” and in this case, the Complainant “failed to demonstrate that the mark was well known in the United States and likely to be known to the Respondent at the time the Respondent acquired the disputed domain name.” As the Panelist insightfully stated, “this was important to reliably infer bad faith, given the nature of the mark and the Respondent’s denial” [emphasis added]. I just love how the Panelist took particular note of the importance of reliability when it comes to making inferences. Inferences can be weak and therefore unreliable or they can be strong and thereby reliable. Here, the Panelist could have drawn a weak inference based upon his sense of skepticism, but acknowledged that to do so would be unreliable and therefore erred on the side of evidence. This is exactly the right approach.

Million Dollar Domain Name: Respondent Did Not and Could Not Have Known of Complainant’s WhatsApp Group

STABLE APP LLC v. Unlimint Holding EU Ltd/ Mr Admin – Cardpay Ltd., WIPO Case No. D2023-2594

<stable .com>

Panelist: Mr. Warwick A. Rothnie

Brief Facts: The promoters for the Complainant Company initially created a WhatsApp group on January 20, 2022, under the name “Stable” to plan and coordinate the design and launch of a new financial service under the name “Stable”. On March 9, 2022, they received a brand strategy proposal from an advertising agency including the design for the proposed business’ trademark – STABLE and noted the disputed Domain Name “may be available”. Thereafter, they engaged the services of GoDaddy domain brokers, who pointed out that the disputed Domain Name, had recently sold for over USD one million and suggested a starting bid of USD $1.2 million. The Complainant applied to trademark STABLE in Colombia on March 28, 2022 (registered in April 2023) and also secured an International Registration (“IR”) for STABLE designating Brazil, Mexico and the United States. On March 30, 2022, the Complainant was incorporated in Delaware in the United States. On October 9, 2022, the Complainant secured the domain name <stable-app .com>, which it currently uses to promote its services. During 2023, the Complainant or its representative made a number of other attempts to secure the rights to the disputed Domain Name.

The Respondent is a licensed Electronic Money Institution in the European Union and the European Economic Area and contends that he acquired disputed Domain Name on February 9, 2022, for a price of USD $1,008,925 in connection with a new service offering it was planning. The disputed Domain Name resolves to a parking page for now but, on August 9, 2022, the Respondent incorporated a new subsidiary in Cyprus under the name Stable Defi Ltd. The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith because there has been no use of the disputed Domain Name since its registration by the Respondent in connection with the Respondent’s commercial activities even after a year and, instead, the disputed Domain Name directed to a webpage stating “stable .com may be available DOMAIN INQUIRIES: info@newreach .com”. The Complainant further contends that the use of the disputed Domain Name in connection with financial services would infringe the Complainant’s trademark.

Held: The difficulty confronting the Complainant is that, generally speaking, a finding that under the bad faith clause requires an inference to be drawn that the respondent in question has registered and is using the disputed Domain Name to take advantage of its significance as a trademark owned by (usually) the complainant. However, the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name a month or so before the Complainant was incorporated on March 30, 2022 and even before the Complainant’s associated company applied to register the trademarks on March 28, 2022. Perhaps recognising this difficulty, the Complainant has pointed out that the promoters started a WhatsApp chat group under the name “Stable” on January 20, 2022. The Panel, however, considers the end-to-end encryption feature of WhatsApp is well-known. The Complainant has not made any attempt to suggest that the Respondent was, or became, a member of the WhatsApp chat group before the Respondent paid over USD one million to acquire the disputed Domain Name.

There does not appear from the record in this case to have been any other public circumstance from which the Respondent could have become aware of the plans for the Complainant’s project. Nor has there been any suggestion that the Respondent, or someone associated with it, was privy to information about the plans to use “Stable” being developed by the Complainant’s backers. In these circumstances, therefore, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to establish that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. So far as the record in this proceeding reveals, the Respondent did not, and could not, have known about the Complainant or its trademark and, accordingly, cannot be found to have registered the disputed Domain Name to take advantage preemptively of the plans of the Complainant and its backers. Accordingly, the Complainant cannot establish the third requirement under the Policy and the Complaint must fail

RDNH: The disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent before the Complainant was incorporated and also before registration of the Complainant’s trademark was sought. In addition, the Complainant’s backers knew from the advertising agency’s presentation before they adopted “Stable” as a trademark that someone already had the disputed Domain Name registered. That knowledge did include the statement that the disputed Domain Name may be for sale. Following up on that knowledge, Mr. Delgado did seek to explore purchase. He authorised a token bid of USD $900 even after being told the holder had paid over USD one million recently. Moreover, the Complaint has sought to characterise the advice being provided by the so-called “domain broker” as avaricial conduct by the Respondent.

It has been established for many years now under the Policy that a second or junior user does not become entitled to a domain name merely because the holder is not using it publicly, at least where there is no evidence that the Respondent has targeted the second comer or otherwise sought to take advantage of the significance of the disputed Domain Name as some other person’s trademark, whether those trademark rights are established or incipient. Given the facts known to the Complainant before the Complaint was filed and especially bearing in mind that the Complainant is professionally represented in this proceeding, the Panel considers it is fair to characterise the bringing of the Complaint in this proceeding as reverse domain name hijacking.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Abello Abogados, Colombia

Respondents’ Counsel: Hogan Lovells (Paris) LLP, France.

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: A particularly well written and well-reasoned decision. It was interesting to see Hogan Lovells (Paris) represent a valuable dictionary-word domain name in a UDRP. Hogan Lovells has represented Complainants very successfully in over 700 cases but this is only the second UDRP defense by Hogal Lovells (Paris), the last one being GameRoom .com in 2021, where Jane Seager and David Taylor were the attorneys of record for the Respondent.

Panel Would Have Awarded Damages and Costs Against University of Montreal

Universite de Montreal v. Heinrich Wunder, CIIDRC Case No. 21210-UDRP

<extenso .org>

Panelist: Hon. Neil Brown, KC

Brief Facts: In 2001, the Complainant’s Faculty of Medicine, through its Department of Nutrition, set up the “Centre de reference sur la nutrition humaine Extenso” (hereinafter referred to as “Extenso”). As part of that activity, the disputed Domain Name was registered on November 19, 2001, but it later ceased to use the domain name and its registration lapsed in November 2022. The Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name and is using it for a website to offer nutrition advice and promote various fat-burning and weight-reduction products by redirecting internet users to external websites, but the Complainant maintains that it has not approved of any of those products.

The Respondent contends that the Complainant has sought to prove ownership of a registered Canadian trademark, which was not renewed and as a result, deleted from the Canadian trademark registry on December 12, 2019. Moreover, the trademark was not registered in the name of the Complainant or gave rise to any trademark rights as it is required to be for the purposes of this proceeding. The Complainant has not proved or sought to prove that it has an unregistered or common law trademark for EXTENSO and has made no claim and offered no evidence of secondary meaning in the word “extenso”.

The Respondent also points out that the Complainant submits that further substantiation of its case on the issue of legitimate interests and bad faith is to be found in a document entitled “Application to institute proceedings” which is said to be annexed to the Complaint. However, no such document is attached to the Complaint or otherwise evident. The Complainant has brought the proceeding without any supporting evidence and in circumstances showing that it has been brought as a case of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking and the Panel should so find. That is particularly so as the Complainant is represented by the Counsel.

Held: The Complainant provides attachments to the Complaint, which certainly reveals a Canadian trademark (not a service mark as claimed) which is certainly recorded in the Canadian trademark database and it is a trademark for EXTENSO. But there are difficulties with it. The first difficulty is that it is dead, being in that state because as the registry states, it has been “cancelled or invalidated and removed from the registry”. The second difficulty with the trademark on which the Complainant apparently relies is that it is not registered in the name of the Complainant, the University of Montreal but in the name of the “CENTRE DE REFERENCE SUR LA NUTRITION HUMAINE EXTENSO” which is not the Complainant in this proceeding. Moreover, the Complainant has not alleged that it has common law trademark rights in EXTENSO and it has certainly not set about proving any.

The Complainant’s further approach on proving its prima facie case under the second clause was to include in the Complaint 3 lines of type and nothing else, which is not an argument or evidence of anything, but a conclusory assertion which is of virtually no value. The Complainant ends the 3 lines of type on this issue (as it later also does on the issue of bad faith) by submitting that further substantiation of its case on this issue is to be found in a document entitled “Application to institute proceedings” which is said to be annexed to the Complaint. However, no such document is attached to the Complaint or otherwise evident to the Panel. Nor has the Respondent been able to find it, which raises at least a question as to whether it is being given a fair opportunity to defend itself if it cannot have access to the evidence that the Complainant apparently relies on.

Lastly, the Panel finds that it has not been shown that the disputed Domain Name was registered and used in bad faith either under the specific grounds set out in the Policy or on any other ground showing what could fairly be described as bad faith. It is simply not bad faith to buy a domain name and use it for your own purposes if that conduct does not impinge in some way on the complainant’s trademark. The Complainant has shown no evidence that this is what the Respondent has done. There is a disturbing and complete lack of evidence produced showing bad faith. Thus, the Complainant’s case fails on the lack of any evidence to show that the Respondent lacks legitimate interest or has registered and used the domain name in bad faith.

RDNH: The Panel’s impression is that the Complainant has been motivated by regret that it voluntarily surrendered the domain name and now does not like the way it is being used. In that regard it is motivated by reasons that have nothing to do with issues arising under the UDRP and cannot have anything to do with the Complainant’s trademarks because it has none. Nevertheless, it went ahead with a baseless case and has put the Respondent, the Panel and the Provider to time and trouble in processing it. In particular, it is scarcely believable that all concerned should be sent off to look for a document entitled “Application to institute proceedings” where the Complainant’s case is said to be found, but where there is apparently no such document.

This whole unsatisfactory situation is in a jurisdiction where the Panel has no power to award legal costs or damages against a failed Complainant. Had it had such power, the panel as presently constituted would have awarded both damages and costs against the Complainant. As the Respondent’s counsel points out, as part of a well-argued submission, this is made all the worse by the fact that the Complainant is legally represented. The Panel, therefore, finds that the Complaint was brought in bad faith in an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking and primarily to harass the Respondent and declares that the Complaint constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Andrea Provencher of Cain Lamarre LLP

Respondents’ Counsel: Peter Muller

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

Initially, this case appeared a lot different to me than how I viewed it after closer examination. Here, the Respondent had apparently copied the Complainant’s former website and deployed it at the Complainant’s former domain name to sell weight loss products – thereby taking advantage of the Complainant’s reputation in nutritional studies. The Complainant, the University of Montreal, was obviously upset and apparently rightly so.

However, with the assistance of the Respondent’s counsel, Panelist Brown was able to unravel the Complainant’s allegations and determined that all was not as it seemed. Indeed, the Complainant’s relied-upon trademark registration had long expired. No common law trademark rights were claimed and this makes sense as the Complainant’s own affidavit apparently stated that the Complainant had ceased operations in 2020 and therefore conscientiously allowed its domain name registration to expire in 2022. Moreover, the Complainant wasn’t even the former trademark owner.

Given the foregoing, the Complaint was properly dismissed. But what about the RDNH? Initially I was hesitant that RDNH was appropriate despite that failings of the Complaint given the activities that the Respondent was engaged made him arguably have “unclean hands”. Ultimately however, RDNH was arguably appropriate, not because the Respondent was “so right” but because the Complainant was “so wrong”. Misrepresentation of trademark rights, bringing the case in the name of the wrong party, and failure to make out any arguable case under the Policy, was deserving of censure as Panelist Brown so found. It was a harsh remedy in the sense of the embarrassment caused, but appropriately so. Indeed, for the Complainant it was lucky that this was a UDRP and not a court case. If this had been a court, the Panelist would have levied costs and damages due to the abusive nature of the Complaint. For litigators particularly in jurisdictions where the “English Rule” of costs following the event is employed, it will come as no surprise that if this had been a court, costs could very well have been levied in the circumstances.

The Domain Name Composed of Descriptive Term

EL Films LLC v. Nina Chang, NAF Claim Number: FA2308002058321

<thecareergirl .org>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a non-profit organization providing education and career counselling services. It owns rights in the CAREER GIRLS mark based on registration with the USPTO (June 18, 2013). The disputed Domain Name was registered in 2016 and resolves to a website that appears to be operated on a non-profit basis, out of the United Kingdom, which provides examples of women working in the STEM space and resources for women interested in different careers. In particular, the “About” page of the Respondent website states that “Our mission is to inspire young women with the huge range of roles open to them, and to equip them with specific (and fascinating!) insights into amazing career paths!”

The Complainant provides considerable evidence of its use of the CAREER GIRLS mark, including, since 2010, the operation of a website at <careergirls .org> where it offers advice and resources for women interested in careers in the United States. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent registered and uses the <thecareergirl .org> domain name in bad faith as it seeks to divert users from the Complainant to its own website where it offers competing services. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent registered <thecareergirl .org> with actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the CAREER GIRLS mark. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Panel finds there are factual and legal issues that are unresolved by the evidence presented and the Panel is of the opinion that this case is not one that is well suited for resolution under the Policy. The Domain Name consists of three generic words “the”, “career” and “girl” with an entirely descriptive meaning (referring to a woman with a career). While the Complainant holds a registered trade mark for the CAREER GIRLS marks in the US only. The Respondent, on its face, appears to operate an entirely legitimate non-profit website advising women about careers under the name “The Career Girl”, from the Respondent’s Website. The record does not indicate that the Respondent has sought to register any other domain names incorporating the CAREER GIRLS mark or similar marks or engage in any other conduct that suggests the use of the Domain Name is anything other than for a bona fide offering of services.

While the Panel accepts that the Complainant has a significant reputation in the CAREER GIRLS mark, it is apparent that its services are primarily offered in the United States. The Panel is not prepared to conclude that the CAREER GIRLS mark is so well-known and ubiquitous that the Panel must find, for that reason alone, that the Respondent’s registration of a domain name containing the words “the”, “career” and “girl” was motivated by the awareness of the Complainant, as opposed to registration of the Domain Name for its inherent meaning. Indeed, the nature of the Respondent’s Website, being a website offering career advice to women, in a different jurisdiction to that where the Complainant trades in, without any obvious evidence of affiliation or misleading conduct, would suggest that the Respondent’s motivation related to the inherent meaning of the terms comprising the Domain Name.

The Complainant has failed to demonstrate that the Respondent lacks rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name. Besides, the Policy is designed to deal with clear cases of cybersquatting, if the Complainant wishes to bring proceedings against the Respondent for trade mark infringement, passing off, or question the evidence of the Respondent’s conduct apparent in the Respondent’s Website; such a proceeding is more appropriately brought in a court of competent jurisdiction.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Tiffany Salayer of Procopio, Cory, Hargreaves and Savitch LLP, California, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Editor, Ankur Raheja: To the Panelist’s credit, the Respondent’s failure to respond did not result in the transfer of the disputed Domain Name. Here, the Panelist conducted limited factual research to ascertain that and concluded: “It appears that Respondent operates a legitimate non-profit enterprise in the United Kingdom offering career advice to young women and there is no evidence that Respondent is seeking to take advantage of any similarity between the Domain Name and CAREER GIRLS Mark beyond that which arises from a truthful use of the terms “the”, “career” and “girl” to describe the services that Respondent provides”.

In fact, a search for the word “Career Girl” in Google at least from India firstly refers to its dictionary meaning at Dictionary .com and then to a movie title by a similar name. It is followed by other dictionaries and a few websites that use the term ‘Career Girl’ in their Domain Name, for example, <careergirldaily .com>, <classycareergirl .com>, <mscareergirl .com>, <corporatecareergirl .com>, however, the Complainant is nowhere to be found on the first page of the search results.

Indeed, it is quite important for any Panelist to weigh the keywords contained in a Domain Name against any generic or descriptive meaning, even in the absence of the Response. The situation would have been different if the Domain Name was comprised of a distinctive combination like in the below matter of <bollorelogistic .us>, but here the matter has been rightly held the favor of the Respondent. This also reminds me of the reasoning laid down by a dissent Panelist Mr. G. Gervaise Davis III in the matter of EducationDynamics, LLC v. Global Access c/o domain admin, NAF Claim Number: FA09050012654891, wherein the descriptive domain name, <elearner .com> was ordered to be transferred away by the majority. The dissenting Panelist in <elearner .com> came heavily against the Complainant (and the system overall) while he stated:

“Suffice it to say, this Dissenting Panelist feels it is poor public policy as well as contrary to the fundamental purpose of the UDRP to protect generic or descriptive trademarks, which has the effect of taking such terms out of the public use, or at least making it difficult for the public to use the English language from which these words are taken.

An example of the absurdity of this practice, here, is found when one uses the Google® search engine to search for the term “elearner.” This results in 76,100 hits, only a few of which have anything to do with Complainant or its website, while the tens of thousands of other hits refer to and use the common and generic terms “elearner,” “elearning,” or terms like “elearning methodology,” which illustrates far more effectively than this Panelist can, that the whole concept of “elearning” is a technical English term and description of a new method of learning that belongs to the public at large and not to some domain name owner who seeks to arrogate ownership of a descriptive or generic English word to itself.

EducationDynamics LLC (Complainant here) does not own the word “elearner” or “elearners,” the public does and any decision like that of the Majority here, which so finds, is simply and regrettably wrong. I have, therefore, respectfully dissented here in some detail so that other Panels in the future do not make what this Panelist sincerely believes is an error of law.”

Typosquatting Attempt by the Registrant

BOLLORE SE v. KLX Aerospace, NAF Claim Number: FA2308002057860

<bollorelogistic .us>

Panelist: Mr. Steven M. Levy, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1822, is a world leader in the business lines of transportation and logistics, communication and media, electricity storage and solutions. It is one of the 500 largest companies in the world with over 56,000 employees. Its subsidiary, Bollore Logistics, is focused on worldwide transport and logistics and operates in 146 countries. The Complainant owns the BOLLORE LOGISTICS trademark in many countries through its registrations with the WIPO and the USPTO as well. It also owns the domain name <bollorelogistics .com> and uses it for a website since 2009. The disputed Domain Name was registered on August 7, 2023, and the Complainant points out that it is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s mark as it simply omits the letter “s” and adds the “.us” TLD.

The Complainant provides a screenshot of the disputed Domain Name’s resolving website, which features pay-per-click links titled “Business”, “Business Organization Chart”, “Planning Management”, “Administrative Management Software”, “Best Trading Platform”, and alleges that the Respondent is seeking commercial gain based on confusion with the Complainant’s mark. The Complainant further alleges given that its BOLLORE LOGISTICS trademark is both distinctive and has gained a substantial reputation such that “it is reasonable to infer that the Respondent has registered the domain name with full knowledge of the Complainant’s trademarks”. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: Using a typosquatted domain name to display a pay-per-click page with links to third-party products or services, shows neither a bona fide offering of goods or services under Policy ¶ 4(c)(ii), nor a legitimate noncommercial or fair use under Policy ¶ 4(c)(iv). Further, the Complainant has made available evidence as to the screenshots from the Complainant’s own website at <bollorelogistics .com>, a document which sets out various of the Complainant’s business statistics such as its number of employees and worldwide sales, and detailed descriptions of the Complainant’s business. While the Panel would prefer to see further evidence of the brand reputation that this marketing material has created, it finds that this evidence does narrowly support the Complainant’s assertion that its mark has gained some reputation. This, combined with the fact that the disputed Domain Name is a typosquatted variation of the Complainant’s own <bollorelogistics .com> web address, leads the Panel to find it more likely than not that the Respondent did have actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in its mark at the time that it registered the disputed Domain Name.

Furthermore, the use of a disputed Domain Name to redirect consumers to third-party goods or services can be evidence of bad faith disruption of a complainant’s business under Policy ¶ 4(b)(iii) and an attempt to attract users for commercial gain under Policy ¶ 4(b)(iv). The Complainant provides a screenshot of the disputed Domain Name resolving to a pay-per-click page with links to others providing business-related services. Based on this evidence, and the fact, that the disputed Domain Name is a confusingly similar typo squatting version of the BOLLORE LOGISTICS mark and Complainant’s <bollorelogistics .com> domain name. The Panel finds that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Nameshield, France

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Although this case appears to be a ‘run of the mill’ cybersquatting case, it is noteworthy that this did not dissuade the Panelist from thoroughly examining the case, weighing the Complainant’s evidence, or from meticulously outlining his reasoning. As a judge once said, the reasons for a decision are for the losing party, not the winning party. It is therefore important for Panelists to explain to the losing party why it lost the case in precise and complete terms, as was done by Panelist Steven Levy in this case.