Drawing an Inference of Bad Faith from An Asking Price

The Converse .co dispute is directly on the fault line created by the different perspectives of a domain investor and a brand owner as to what is, or is not, permissible under the UDRP. It would make a great moot UDRP session, in the model of the one on redball.com from 2021 that was jointly presented by INTA and the ICA (excerpt here), as both sides can make strong, well-supported arguments, as indeed they did here. (continue reading commentary).

SIGN UP FOR THE INAUGURAL “LEVINE LECTURE” HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.23), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Drawing an Inference of Bad Faith from An Asking Price (converse .co *with commentary)

‣ Is “Acrobat” a dictionary word or a famous mark? (acrobat .ai *with commentary)

‣ Claimed Confusing Similarity is a “Stretch” (opns .domains *with commentary)

‣ Back to the Beech (hiobeech .com *with commentary)

‣ A Sweet Transfer for the Chocolatier (lindtt .com *with commentary)

‣ Domain Name Consists of Commonly Used Dictionary Words (redlion .site)

Drawing an Inference of Bad Faith from An Asking Price

All Star C.V., Converse, Inc. v. Narendra Ghimire, WIPO Case No. DCO2024-0014

<converse .co>

Panelists: Mr. Lawrence K. Nodine (Presiding), Ms. Reyes Campello Estebaranz and Mr. Andrew D. S. Lothian

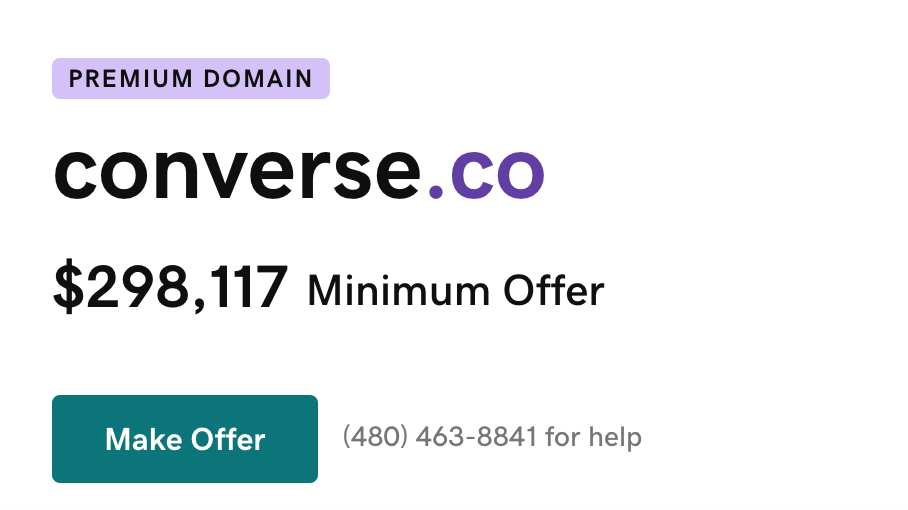

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the legal owner and controller of the CONVERSE trademark, which it has used since 1908 to produce and sell shoes and related merchandise. The Complainant owns many trademark registrations worldwide for the CONVERSE mark, including United States registrations dated February 3, 2004, and November 21, 2006, and a Colombian registration dated April 16, 1986. The Complainant acquired the domain name <converse .com> in 1995, where it promotes and commercializes internationally its products. The Respondent is a domain investor or “domainer”, who acquired the disputed Domain Name on October 5, 2019, in an auction for USD $309. The disputed Domain Name resolves to a GoDaddy-branded landing page at <afternic .com> that indicates the disputed Domain Name is for sale and a separate GoDaddy Domain Name Search webpage catalogs the disputed Domain Name as a “premium domain” and offers it for sale as a minimum offer price of GBP 235,275 (approx. USD 300,000).

The Complainant offers evidence that the CONVERSE trademark is globally famous and alleges that it is implausible that the Respondent was not aware of the Complainant when registering the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant further argues that the high asking price for the disputed Domain Name more likely than not reflects the significant value and goodwill attached to the CONVERSE mark, not any “dictionary meaning” of the word “converse”. The Respondent contends that the “Converse” is a generic word available for anyone to use so long as it is not a business in association with sneakers in the locations where the Complainant has senior trademark usage for which the Respondent acknowledges the Complainant is well known. The Respondent further contends that the Complainant has not provided the required proof that the Respondent had Complainant in mind when acquiring the disputed Domain Name and that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name “primarily for the purpose of selling the domain name registration to the owner of the trademark”, as no such evidence exists.

Held: The Respondent concedes that he was aware of the Complainant and its rights but contends that those rights are limited to sneakers and that, regardless, the Complainant has not proved that the Respondent targeted the Complainant. The Respondent contends that the word “converse” has an ordinary dictionary meaning that a hypothetical future purchaser may legitimately exploit and that there are many third parties around the world who own trademarks that include “converse”. The Panel rejects these arguments for several reasons. The Respondent concedes awareness of the Complainant and its rights. In addition, the Panel finds, based on the extensive evidence recited above, that the Complainant’s CONVERSE mark is famous globally, and especially in the United States where the Respondent resides. These two factors—Respondent’s admission and the Complainant’s fame—distinguish the several prior cases where the Respondent prevailed because the panels found that the Complainant did not overcome the Respondent’s denials “on penalty of perjury” that he had no knowledge of the respective Complainant’s rights before he registered the challenged domain names.

Further, the Respondent set the purchase price for the disputed Domain Name at GBP 235,275 (approximately USD 300,000). While the Panel understands dictionary word domain names can fetch a high price tag, this price likely filters out buyers who are interested in the non-trademark meaning of the term “converse”. The Panel also infers that the Respondent, an experienced domain name investor, was likely aware that the price would filter out purchasers interested in only the dictionary, geographic, or surname connotations of the term. The Panel, therefore, infers that the price was knowingly set to limit the set of potential purchasers with a particular focus on the owner of both the CONVERSE mark and the valuable Domain Name. The Respondent rightly defends that the Policy does not prohibit a domain name owner from charging a buyer any price it wishes, but that misses the point, which is that, when combined with the Respondent’s admitted awareness of the famous mark, the price is a window into the Respondent’s probable intent. Finally, the existence of other marks or company names including the word “converse” is not an argument that may justify Respondent’s conduct or may indicate bad or good faith under the Policy, unless other circumstances of the case indicate bad or good faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Stobbs IP Limited, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: Greenberg & Lieberman, United States

Case Comments by ICA Director and Domain Name Investor, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

The Converse .co dispute is directly on the fault line created by the different perspectives of a domain investor and a brand owner as to what is, or is not, permissible under the UDRP. It would make a great moot UDRP session, in the model of the one on redball.com from 2021 that was jointly presented by INTA and the ICA (excerpt here), as both sides can make strong, well-supported arguments, as indeed they did here.

Elliot Silver articulates a domain investor’s view of the case in his blog post, Converse.CO UDRP Decision Turns on Price Inference. As Elliot wrote:

My interpretation is the panel believed that the price was set high enough that the only realistic buyer would be the well-known Converse brand. In my opinion, this is flawed thinking.

As a domain investor, I would look at it another way. If I owned Converse .CO, I would imagine Converse would have little interest in the lesser value .CO domain name. If you already have the .com, you don’t need the .CO. I would also assume that any company that wants to brand itself as Converse .CO – an AI or other similar type of company – would understand potential risks of sharing a brand space with Converse. They would know their offering needs to be distinct from the sportswear and shoe company, and they would also know there could be a legal battle. This type of buyer would have ample funding and a legal war chest to protect the brand they are building. As such, a company interested in creating a different Converse brand would be able to pay the ask. Additionally, it is an asking price and perhaps the number to get it done is lower.

In general, domain name investors believe that UDRP panelists have no business evaluating whether the price of a domain name is realistic or not. Most UDRP panelists have no expertise in domain name valuations. Domain name valuation is challenging even for the most experienced domain name investors. It does not help that there is very little transparency as to the high end of the market, as nearly all high-dollar transactions are covered by non-disclosure arrangements so that the purchase prices are never publicly disclosed. For instance, a domain name broker recently shared that he had helped facilitate a $2 million sale, yet could not reveal the domain name.

Panelists can easily get tripped up when they presume to draw inferences from the asking price of a domain name, as did all three members of the panel in the ADO.com dispute from 2017. The ICA’s statement on the decision noted:

In the recent ado .com UDRP decision, the panel made the speculative and factually incorrect finding that a “high” asking price indicated bad faith targeting of a trademark. The UDRP is intended to address clear-cut cases of cybersquatting, not to second guess the asking prices set on inherently valuable domains in an open and competitive marketplace. This overreaching decision undermines ownership rights to domain names as an investment asset class and destabilizes the multi-billion-dollar aftermarket in domain names.

Indeed, after an expensive court battle forced on the domain registrant by the panel’s decision to transfer the domain name, the registrant was validated in a settlement that recognized that the registrant’s ownership of the ado.com domain name was lawful.

Yet, from a brand owner’s perspective, a very high asking price can be useful evidence as to the respondent’s intentions in registering the disputed domain name. If the asking price is only plausible if it is targeted at the brand value created by the brand owner, then the price can be seen an indicator as to whether the registrant registered the domain name due to its value as a dictionary word or generic phrase, or instead due to classic cybersquatting on the goodwill created by the brand owner.

The language of the UDRP, in section 4(b)(i) requires a panel to ascertain whether the respondent acquired the disputed domain name “primarily for the purpose of selling” it to the Complainant. Where the Complainant’s brand is based on a widely used dictionary word like “converse”, the most salient evidence in drawing an inference as to whether the registration was “primarily for the purpose of selling” the domain name to the Complainant may be the asking price. This is the position taken by the Panel, which states that “the price is a window into Respondent’s probable intent.” From this perspective, a panel would be remiss in failing to draw reasonable inferences from the asking price.

Yet, as discussed above, attempting to draw reasonable inferences from an asking price places the panel in a very fraught situation. In Converse .co there was no direct targeting. Although the landing page hosted by the Afternic marketplace was merely a contact form, a search on the Afternic website indicates that the asking price is nearly $300,000.

While the Complainant is the dominant user of the Converse mark, it is not the only user. When I search “converse” on Google, the first page of results also includes results for Converse University, the dictionary definition of “converse”, the City of Converse, Texas, and Converse county, Wyoming. Converse University is reported to have an endowment of over $160 million and recently received a $10 million bequest. If Converse University wished to expand into for-profit arenas, for example, the Converse .co domain name might appeal to them and they apparently have the financial means to make a substantial offer should they so wish.

Moreover, the dictionary meaning of “converse” is inherently appealing and similar domain names have attracted high valuations. One of the most expensive domain names ever sold is Voice.com at $30 million. “Voice” and “converse” have related meanings. Similarly, Speak is a mobile app that has raised over $20 million and operates on the Speak .com domain name. Converse .co could attract a substantial offer based on its dictionary meaning alone entirely unrelated to the Complainant’s sportwear and shoe offerings. For instance, Converse Health has an offering that uses AI to help clinics communicate with their patients and uses the Converse.Health domain name. This suggests the many non-infringing uses to which Converse .co could be put.

Panelists have the challenging task of assessing evidence and drawing subjective inferences of bad faith from that evidence. In this sense, the UDRP functions as a smell test, as I wrote in “Smells Like Cybersquatting? How the UDRP ‘Smell Test’ Can Go Awry”. In the article, I explain that since domain name investors in general only sell such a miniscule percentage of our portfolio each year, the only way the business model works is if domain names can realistically be priced at a high multiple of the acquisition cost, such as 5 times to 20 times the purchase price:

Only in this way can the very small percentage of domain names that sell each year generate sufficient revenue to make it a viable business. As a rule of thumb, an investor will usually be willing to commit $1000 to acquiring a domain name only if she believes that it can sell for between $5,000 to $20,000 or more.

The trouble that panels can get into by their lack of knowledge of the domain investor business model and by making misguided inferences from an asking price is demonstrated in the victron.com dispute from 2022, where the disputed domain name was transferred over a dissenting view. In the Victron .com dispute, the Respondent acquired the domain name for $7,000. The majority held:

The Respondent has not specified the exact amount that it was looking for as price of the disputed domain name. A 5-figure amount would be anywhere between USD 10,000 and USD 99,999. Even if the lowest figure is taken, it would still make a 43% profit, and will be well in excess of the Respondent’s documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the acquisition of the disputed domain name, which it states were equal to USD 7,000.

Yet a domain name investor acquiring a domain name for $7,000 and then offering it for sale for $10,000 is not evidence of targeting the complainant. An investor would promptly go broke buying domain names for $7,000 and selling them for $10,000 given that a sell-through rate of 2% is considered desirable. The reasoning in victron .com demonstrates the perils of incorrect inferences from an asking price.

Yet, despite the long odds and all the risks inherent in a panel’s attempt to draw inferences from a n asking price, the converse .co decision is, in my view, a rare instance where the panel’s “smell test” may have worked and its inference may have been justified. As I mentioned in the “Smell Test” article above, given the very small chance that any specific domain name will find a buyer, investors usually require the possibility of a 5x to 20x return when acquiring a domain name at auction to justify the purchase. Conversely, what this means is that in a competitive bidding situation, the bids will often reach 1/5th to 1/20th of the expected end-user sales price. Sometimes investors get lucky, especially on domain names acquired for $500 or less, and may be able to resell the domain name for a 50x or 100x multiple. Yet it would be extremely unusual for a domain name that had a recognized resale potential of $300,000, based solely on the inherent appeal of the domain name, to fetch only $306 such that it sold for 1/1000th of its potential resale value. Yet that is what the Respondent claimed happened with converse .co.

That such a scenario is quite unlikely suggests that the inherent value of the domain name is far less than $300,000. It also suggests that by setting an asking price of $300,000, the Respondent could reasonably be inferred to have targeted the value of the goodwill created by the Complainant. The Panel took a similar view:

The Panel notes that Respondent has disclosed it purchased the Disputed Domain Name for USD 306, and, the Panel simply finds it implausible that Respondent immediately directed the Disputed Domain Name to Afternic, placing it for sale for approximately USD 300,000, merely in consideration of the dictionary value of the term “converse”.

The Panel likely does not have sufficient familiarity with the domain name aftermarket to rely on reasoning such as I offer above, yet let’s say for the sake of argument that in this dispute the Panel made a reasonable inference of bad faith due to the asking price. Yet even if the Panel got it right in this instance, this does not mean that most panels can avoid being tripped up by the numerous pitfalls they face in attempting to make inferences of bad faith due to an asking price.

The word “converse” is registered in nearly 300 TLDs, most apparently unconnected to the Complainant, and many offered for sale by domain name investors. What if the sales price of a “converse” domain name in one of these extensions instead of being $300,000 was $50,000, or $10,000 or $5,000? It places a panel in an untenable position of having to determine at what point an asking price is more likely than not based on the complainant’s goodwill in its mark rather than on an optimistic assessment of the inherent value of the domain name. Each panelist will make this subjective inference differently. This showcases the limitations of this approach and that it is ultimately a dead end.

It is no surprise that the “primarily for the purpose of selling” language found in the UDRP is over 25 years-old, and dates from an ancient era where there were still only a handful of TLDs, where classic cybersquatting of the dot-com domain names of famous brands still occurred, and when domain name investing was in its infancy. It is ill-suited for the current reality of a mature aftermarket in domain names and where a second level domain name based on a common word or phrase that is also an exact match to a well-known trademark can be registered in hundreds of different TLDs by a large number of unrelated owners.

The underlying goal of the UDRP is to protect brand owners from harm. This raises the question of how the Complainant was harmed by the Respondent acquiring Converse .co and offering it for sale for around $300,000. The Complainant uses Converse .com and has no need of the .co extension. If the Complainant is correct that the domain name does not have a value of $300,000 to any third-party, then the domain name will sit unsold, harming no one. If the Complainant is incorrect, and an unrelated start-up successfully negotiates to acquire the domain name for a non-infringing purpose, such as Converse Health does with its Converse.Health domain name, then again, the Complainant is not harmed.

A flaw with the UDRP is that it relies on a highly subjective assessment of bad faith intent rather than an objective assessment of whether the Complainant is being harmed. Is it fair that Ovation.com is lost in a UDRP because the registrar placed a PPC link that referenced one of the Complainant’s products on a landing page? Does the Respondent deserve to lose a domain name it acquired for a substantial sum due to PPC ads that generated perhaps $10 in revenue to the registrar? There can be an enormous disproportion to the major harm inflicted on a Respondent to avoid a negligible alleged harm to a Complainant.

Is “Acrobat” a dictionary word or a famous mark?

Adobe Inc. v. Zhizhong Zeng, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002095533

<acrobat .ai>

Panelist: Mr. Fernando Triana, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant owns the trademark ACROBAT in the United States of America, registered on April 26, 1994 (first use: June 15, 1993). The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name redirects to a website advertising the disputed Domain Name for sale to the general public, which is not a bona fide offering of goods or services nor a legitimate non-commercial or fair use. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent knew of the Complainant’s trademark ACROBAT before acquiring the disputed Domain Name and used the trademark ACROBAT to create a likelihood of confusion aimed to divert consumers to the Respondent’s website.

The Complainant also sent a letter to the Respondent requesting that the Respondent make no further use of the disputed Domain Name and transfer it to the Complainant. The Respondent replied on April 19, 2024, asserting that their registration and use of the disputed Domain Name was based on the dictionary meaning of the term “Acrobat”. Herein as well, the Respondent contends that “Acrobat” is a widely used English word, it has existed long before the product Acrobat was launched (which has only existed for 30 years). The Respondent acknowledges that the Complainant owns a few of the trademarks ACROBAT in many countries, but they do not own the trademark acrobat exclusively.

Held: The Respondent states that the Respondent uses the word of the English language acrobat but not associated with the Complainant. However, the Respondent failed to prove that before receiving the written notice of the Complaint he was using or preparing a website to use the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. Simply stating that the disputed Domain Name is on sale is not evidence of Respondent’s rights or legitimate interest in it. Further, the Respondent is not making a legitimate non-commercial or fair use of the domain name, without intent for commercial gain to misleadingly divert consumers or to tarnish the trademark or service mark at issue, since the use of the Complainant’s trademark in the disputed Domain Name misleads visitors into thinking that the Complainant is somehow connected to the Respondent. This Panel believes that the Respondent failed to prove his rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

This Panel deems that the mere fact of knowingly incorporating a third party’s trademark in a domain name constitutes registration in bad faith. Further, it is reasonable to conclude that many Internet users would suppose that the websites to which the disputed Domain Name resolves have a connection with the Complainant. This disrupts Complainant’s business, especially since the Respondent did not prove that the use was for another purpose different from attracting, for commercial gain, Internet users to its website, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s trademark. The Respondent’s use falsely suggests sponsorship and/or endorsement by the Complainant of Respondent’s websites and use of the disputed Domain Name. Hence, the Respondent has registered the Domain Name for the purpose of disrupting Complainant’s business, and it is indicative of bad faith registration and use pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii).

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Griffin Barnett of Perkins Coie LLP, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by Panelist, Igor Motsnyi:

Igor is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal, motsnyi .com , “Linkedin”.

His practice is focused on international trademark matters and domain names, including ccTLDs disputes and the UDRP. Igor has over 22 years of experience in international TM and IP matters.

Igor is a UDRP panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy.

The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

When you hear “acrobat”, what comes to your mind? Is it “a person who entertains people by doing difficult and skilful physical things, such as walking along a high wire” as defined here or is it a product of “Adobe”? While it is hard to find an Internet user who is unfamiliar with “Adobe Acrobat Reader”, “acrobat” is also a dictionary word that allegedly comes from the Middle Greek word “’akrobátēs”, meaning “tightrope walker”, see “Merriam Webster” online dictionary.

The <acrobat .ai> decision, in my opinion, raises a number of issues important for further development of UDRP jurisprudence and I would highlight the following:

- Does registrant generally have rights to register a dictionary word domain with the purpose of offering it for sale to the general public?

- Was Respondent acting in bad faith in the circumstances of this case, in particular, did he register the disputed domain name to take an unfair advantage of Complainant?

The tricky part of the <acrobat .ai> decision is that, in my opinion, it is hard to give definite answers to these questions.

1. WIPO Overview 3.0 states that “In order to find rights or legitimate interests in a domain name based on its dictionary meaning, the domain name should be genuinely used, or at least demonstrably intended for such use, in connection with the relied-upon dictionary meaning and not to trade off third-party trademark rights” (sec.2.10.1). However, in sec. 3.1.1 the Overview states: “panels have found that the practice as such of registering a domain name for subsequent resale (including for a profit) would not by itself support a claim that the respondent registered the domain name in bad faith with the primary purpose of selling it to a trademark owner (or its competitor)”.

UDRP panels accepted rights and legitimate interests of domain investors to register domain names corresponding to dictionary words/other attractive terms in the absence of bad faith. In the <acrobat .ai> case Respondent did not seek to use the disputed domain name in its dictionary sense, rather he offered the domain name for sale to the general public. While this is not, under WIPO Overview 3.0, in itself may not be sufficient to establish rights or legitimate interests, it also per se does not negate rights/legitimate interests and does not establish Respondent’s bad faith.

When it comes to “acrobat” one thing is clear: arguably it is a well-known mark of “Adobe Inc”. At the same time, it clearly is a dictionary word. This word can be used by various individuals, organizations and businesses. Therefore, it can be attractive to other businesses and individuals and there may be numerous potential buyers of any <acrobat> domain name.

2. Did Respondent target Complainant in the <acrobat .ai> case? Again, it can be argued both ways. Complainant is, arguably, the most known user of the “Acrobat” mark. There have been recent news reports about the use of “AI” technology by Complainant, including introduction of “AI Assistant for Acrobat”. Therefore, allegedly “acrobat” plus the <.ai> extension may indicate targeting of Complainant.

On the other hand, <.ai> domains have become very popular recently and they are registered for various purposes, often not directly connected with the use of AI technology. Was the choice of <.ai> TLD an indication of targeting sufficient for the purpose of the Policy?

Be it as it may, any “AI” related arguments were not included in the decision.

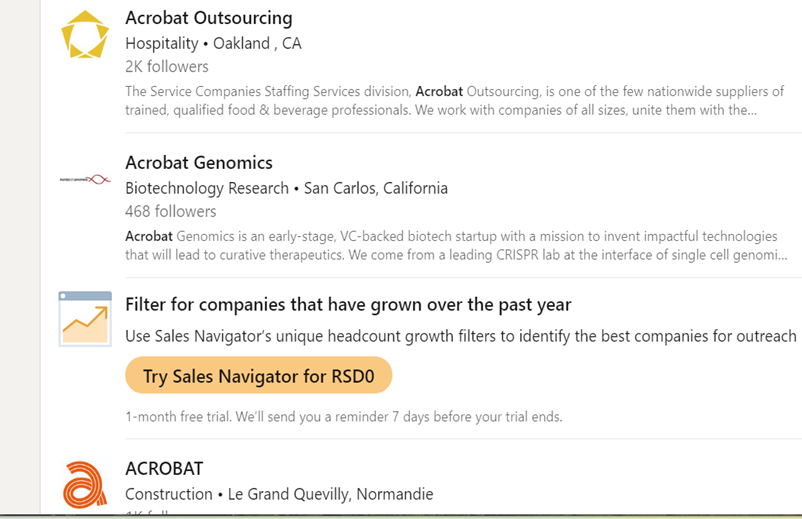

Complainant is by far not the only user of “acrobat” and not the only owner of “Acrobat” marks. A simple “LinkedIN” search reveals numerous businesses using “Acrobat” as part of their names, see below

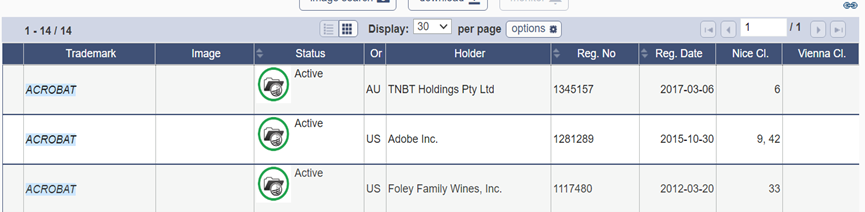

Search of trademark databases demonstrates that different businesses own “Acrobat” trademarks, Complainant is not the only one and Respondent’s arguments that while “Complainant owns a few of the trademarks ACROBAT in many countries, but they do not own the trademark acrobat exclusively” were not without merits. My own USPTO search revealed eighteen (18) pending and registered “Acrobat” marks, 6 owned by “Adobe Inc” and 12 owned by other holders. The WIPO Madrid database brings the following search results with 3 live international trademarks consisting of “Acrobat” only all owned by different holders.

While Adobe Inc. owns <acrobat .com>, it does not own many other <acrobat> domain names and some of such <acrobat> domains are currently offered for sale.

Targeting can be evident either from the website content (e.g. content relating to Complainant) or from domain name composition (trademark plus terms related to Complainant’ activity). There can also be circumstantial evidence of targeting. There was no direct evidence of targeting in this case based on the information available in the decision.

I found only two previous UDRP decisions involving the Complainant’s “Acrobat” mark: Adobe Systems Incorporated v. Domain OZ, WIPO Case No. D2000-0057 (<adobeacrobat .com> and <acrobatreader .com>) and Adobe Inc. v. Rzak Musah, Forum FA2311002069194 (<adobe-acrobat-download .com>). Notably, these two cases are very different from the <acrobat .ai> case.

It is unlikely that Respondent was unaware of Complainant’s use of the term “acrobat”. However, was Complainant a primary/only target since “acrobat” is a dictionary word and is used by other businesses and other businesses/individuals may find this domain name attractive?

To me, we are left with some tough questions that cannot be easily answered.

Will this decision open floodgates of UDRP complaints against domain names that consist of only dictionary words in the absence of direct evidence of targeting?

I am curious to know what our readers think of the <acrobat .ai> decision and its possible ramifications.

Claimed Confusing Similarity is a “Stretch”

The Optimism Foundation v. Feiling Huang, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002095155

<opns .domains>

Panelist: Ms. Francine Siew Ling Tan

Brief Facts: The Complainant, through its OPTIMISM and “OP services” mark, provides a secure platform for digital currency and blockchain transactions. The Complainant claims OPTIMISM brand is well-known for secure access to digital currency and owns US trademark registration dated August 15, 2023. The Complainant further claims common law rights to the OP mark and Logo, based upon use in commerce since 2019, and the Logo since 2020. The Complainant argues that the “OPNS” is an abbreviation of its OPTIMISM mark (“OP”) and an acronym of “name service” (“NS”), and that because there are earlier panel decisions which have found that abbreviations of marks are sufficient to find confusing similarity with those marks for paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy, therefore the disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s marks. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 9, 2023, and the Complainant alleges that the Respondent aims to exploit the Complainant’s reputation for personal gain by using the Complainant’s trademarks and Logo on its website.

The Respondent contends that on March 17, 2023, Web3 Investments Ltd., an affiliate of the Respondent, filed a trademark application for “OPTIMISM NAME SERVICE” and following this, the Respondent used the disputed Domain Name for business activities related to domain names and claims common law rights in “Optimism Name Service” and “OPNS.” He further adds that OPNS is not similar to OPTIMISM. OPNS stands for “Optimism Name Service” and is not an abbreviation of OPTIMISM. The Respondent further contends that the Respondent registered and used the Domain Name for its descriptive value and has established social media influence and public recognition in the Web3 domain registration field. Moreover, the Respondent’s website clearly states no affiliation with the Complainant, preventing confusion.

Preliminary Issue: The Rules do not make provision for supplemental filings except at the request of the panel. While panels have the authority under Paragraph 10 of the Rules to determine the admissibility, relevance, materiality and weight of the evidence, panels are also to conduct the proceeding “with due expedition” (see WIPO Overview, section 4.6).

The Panel notes that the Supplemental Filing was made 6 days after the filing of the Response. Complainant’s Supplemental Filing provides rebuttal to Respondent’s arguments. Supplementary filing by a complainant for the mere purpose of responding to points raised by the respondent which could otherwise have been raised in its complaint is not reason enough to allow the supplemental filing. There is no indication that the Supplemental Filing provides evidence which was not available to Complainant when the Complaint was filed, or which is pertinent and could not have possibly been included in its original filing. The Panel finds no “exceptional circumstance” or crucial information which necessitates allowing the Supplemental Filing. Accordingly, in the exercise of the Panel’s discretion under Paragraph 10 of the Rules, the Panel declines to consider the Supplemental Filing in the rendering of this Decision.

Held: The Complainant has established it has rights in the OPTIMISM trademark. Additionally, the Complainant asserted that it has common law rights to and “owns U.S. trademark applications” in the OP trademark. However, the Complainant failed to provide evidence showing extensive, continuous and well-publicized use of the OP mark which would persuade the Panel of the fame of the OP mark, or that the public primarily associates the OP mark with the Complainant. The mere indication that the OP mark has been used since 2019 alone does not prove that the mark has acquired a secondary meaning. The Panel therefore finds that the Complainant has failed to show it has common law rights in the OP mark. Hence, the issue to be considered in relation to paragraph 4(a)(i) of the Policy is whether the disputed Domain Name which consists of the letters “opns” is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s OPTIMISM trademark.

To state that the letters “opns” in the disputed Domain Name are confusingly similar to the trademark OPTIMISM and that the disputed Domain Name “incorporates Complainant’s trademarks” is a stretch, since the trade mark OPTIMISM is not at all recognizable within the domain name. Further, the Complainant has not brought evidence demonstrating that “OPNS” is a common abbreviation for the Complainant’s trademark OPTIMISM. The Panel, therefore, finds no justification in making a finding in favor of the Complainant on this point, especially in the absence of clear, incontrovertible evidence demonstrating that the letters in the Domain Name are indeed a common abbreviation for the Complainant’s OPTIMISM mark. Mere assertions without foundation and supporting evidence are insufficient.

The Complainant has established it has rights in the OPTIMISM trademark. However, the OPTIMISM trademark is not reproduced nor identifiable within the disputed Domain Name. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the disputed Domain Name is not identical or confusingly similar to the OPTIMISM mark.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Matthew Passmore of Cobalt LLP, California, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Jianzhi Jin of Man Kun Law Firm, Shanghai, China

Case Comments by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: First, bookmark this case for its nice and concise basis for refusing an unsolicited supplemental submission:

”The Panel notes that the Supplemental Filing was made 6 days after the filing of the Response. Complainant’s Supplemental Filing provides rebuttal to Respondent’s arguments. Supplementary filing by a complainant for the mere purpose of responding to points raised by the respondent which could otherwise have been raised in its complaint is not reason enough to allow the supplemental filing. There is no indication that the Supplemental Filing provides evidence which was not available to Complainant when the Complaint was filed, or which is pertinent and could not have possibly been included in its original filing. The Panel finds no “exceptional circumstance” or crucial information which necessitates allowing the Supplemental Filing. Accordingly, in the exercise of the Panel’s discretion under Paragraph 10 of the Rules, the Panel declines to consider the Supplemental Filing in the rendering of this Decision.”

Second, I appreciate how the Panel made the important distinction between mere use of a term (as a basis for claiming common law trademark rights) and the requirement to provide evidence of secondary meaning in order to establish trademark rights: “The mere indication that the OP mark has been used since 2019 alone does not prove that the mark has acquired secondary meaning”. This is an important distinction that is sometimes lost on Panels. It is often insufficient to prove common law trademark rights merely through simple use. Something more is required. How much more will often depend on the nature of the term being claimed as a common law trademark right. Here, the Panel stated that it would require “extensive, continuous and well-publicized use of the OP mark which would persuade the Panel of the fame of the OP mark, or that the public primarily associates the OP mark with Complainant”. I

I also particularly appreciate how the Panel appropriately held the line on the confusingly similar test. As I have written previously, sometimes Panels will virtually “give away” the first part of the test on the basis that it is a “mere standing requirement” and not give it the seriousness that it sometimes deserves. Here, the Panel stated:

“Complainant has failed to show that it has common law rights in “OP”. To state that the letters “opns” in the disputed domain name are confusingly similar to the trade mark OPTIMISM and that the disputed domain name “incorporates Complainant’s trademarks” is a stretch, since the trade mark OPTIMISM is not at all recognizable within the domain name.”

This is a good reminder: Don’t stretch. If it is a “stretch” that probably means that you are stretching to find confusingly similar and even if you are a particularly limber Panelist, you are not expected to engage in stretching, nor should you.

Back to the Beech

Textron Innovations Inc. v. Mike Brannigan / Dquery.io, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002095240

<hiobeech .com> and <bayareabeech .com>

Panelist: Mr. Sebastian M W Hughes

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1923, is an affiliate of Textron Inc. and the successor-in-title to the Aircraft Company, Beechcraft. The Complainant owns several registrations for the trademark BEECHCRAFT, including the U.S. trademark issued on November 5, 1963. The disputed Domain Names resolve to the same website, used by the Respondent to sell pre-purchase inspection, flight training and relocation services relating to the Complainant’s Beechcraft aircraft. The Complainant alleges that the website uses the Beechcraft name and features imagery of the Complainant’s Beechcraft aircraft, and the Respondent is trying to capitalize on the confusion that consumers will likely have when navigating to the Website and unfairly profit from such illegitimate and unauthorized use of the disputed Domain Names.

The Respondent is an FAA-Certified Flight Instructor and, since 2012, an authorized American Bonanza Society Instructor under its “Beech Pilot Proficiency Program”. The Respondent contends that he uses the disputed Domain Names to promote his business of providing pre-purchase inspections for purchasers of second-hand Beechcraft aircraft, flight training services and relocation services for Beechcraft aircraft. The Respondent further contends that he does not compete with or sell any of the Complainant’s aircraft on the website, which features a prominent disclaimer, and any visitor to the website in search of the Complainant’s products would not be confused. The Respondent requests that the Panel make a finding of RDNH.

Held: The disputed Domain Names were registered on June 19, 2010, and September 21, 2021, respectively. The Respondent does not use the website to offer for sale or sell the Complainant’s goods under the trademark. Further, the website contains a prominent disclaimer. The Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Names meets the established Oki Data test:

- He uses the site to provide services related only to the Complainant’s trademarked goods and no other aircraft;

- The Website accurately discloses that Respondent has no relationship with Complainant; and

- He is not trying to corner the market in domain names relating to the Trademark.

The Panel also finds that the disputed Domain Names have not been registered and used in bad faith. The evidence demonstrates that the Respondent has not used the disputed Domain Names to compete with the Complainant, to disrupt the business of the Complainant, or to illegitimately capitalize on any consumer confusion. To the contrary, there is no evidence of any consumer confusion, and the evidence suggests that, if anything, the Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Names is complementary to (and complimentary of) the Complainant and its Beechcraft brand.

RDNH: The Complainant is legally represented and accordingly ought to be held to a higher standard. The Respondent has used the disputed Domain Names in respect of the website for several years without complaint. The Complainant did not furnish any evidence of consumer confusion. Considering the facts of this case, including in particular the prominent disclaimer on the resolving website, the Complainant ought to have appreciated that it would be unable to establish both the second and third limbs under paragraph 4(a) of the Policy in this proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Jeremiah A. Pastrick, Indiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comments by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

This rather brief decision needn’t have been any longer nor more complex. It was ultimately a simple matter that was handily resolved by the Panelist. It is difficult to conceive of a more bona fide nominative fair use scenario than in this case. The Respondent was offering bona fide Beechcraft related services that were not competitive with the Complainant and of course, needed to minimally employ a reference to the “Beech” aircraft in his domain name in order to properly describe his offering. What’s more and as the Panel pointed out, he even had a nice disclaimer. What more could you want from this Respondent? He was not a cybersquatter and the Complainant apparently is just going after any domain name that references its products without regard for the confines of the UDRP – or of the law of nominative fair use for that matter. That is why the Complainant was deserving of RDNH. It should maybe carefully consider bringing a UDRP next time so as to avoid a second finding of RDNH. PS, You will recall that in Digest Vol. 4.21, this same or related Complainant had its case dismissed against another Respondent inter alia for failure to Respond to the Panel’s Order.

A Sweet Transfer for the Chocolatier

<lindtt .com>

Panelist: Mr. Steven Levy Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1845, is a well-known chocolate maker based in Switzerland and sells products under the trademark LINDT, among others. The Complainant has more than 14 thousand employees and made a revenue of CHF 5.2 billion in 2023. The Complainant also owns related Domain Names including <lindt .com>, <lindt .ch>, and <lindt .co .uk>. The Complainant is the owner of numerous trademark registrations including the German trademark (registered on September 27, 1906), United States trademark (registered on July 9, 1912) and international trademark (registered on March 2, 1959).

The disputed Domain Name was registered on March 14, 2024. The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name is confusingly similar to the Complainant’s trademark as it is an obvious misspelling thereof, only adding the letter “t” to the word LINDT and resolving to a parking page with commercial pay-per-click links. The Complainant further adds that typo squatting of the Complainant‘s well-known trademark for a domain name that resolves to a website with monetized links with active MX records indicates that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is used in bad faith. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Policy outlines three examples under Paragraph 4(c) of a policy regarding the use of domain names:

- Paragraph 4(c)(i): Past decisions indicate that using a domain name similar to a well-known trademark for monetized pay-per-click pages is not considered a bona fide offering.

- Paragraph 4(c)(ii): Relevant information includes the WHOIS record and any assertions by the complainant about the respondent’s identity.

- Paragraph 4(c)(iii): The respondent’s use of a domain name for a pay-per-click website does not qualify as fair use, such as news reporting, commentary, or educational purposes.

The panel concludes that the respondent has no rights or legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name according to paragraph 4(a)(ii) of the policy, as there was no response to rebut the Complainant’s assertions.

The Complainant must further show, by a preponderance of evidence, that the disputed Domain Name was registered and used in bad faith under paragraph 4(a)(iii) of the Policy. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent knew about and targeted the LINDT trademark when registering the Domain Name, indicating bad faith. The Complainant points out that the Domain Name is used for a pay-per-click site to divert users through confusion with the trademark and highlight the presence of Mail Exchange (MX) records, suggesting potential e-mail phishing or fraud. The disputed Domain Name is a typo-squatted version of the Complainant’s trademark and is used for commercial gain through user confusion. Based on the foregoing arguments and a preponderance of the submitted evidence, the Panel finds that the disputed Domain Name is being used to seek commercial gain based on a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s trademark under paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Silka AB

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comments by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

The Panel thoroughly examined this case before deciding for the Complainant even when it seemed like a rather sure-thing case for transfer. This is a god example of the Panel taking its duties seriously and making the effort to not just do justice but ensure that justice is also seen to be done.

Domain Name Consists of Commonly Used Dictionary Words

Red Lion Controls, Inc. v. 乔泽 (Qiao Ze), WIPO Case No. D2024-1561

<redlion .site>

Panelist: Mr. Matthew Kennedy

Brief Facts: The Complainant describes the business of the Red Lion Family of Hotels, founded in 1959, operating over 1,200 hotels and properties in eight countries under 17 brands, which was acquired in 2021 by Sonesta International Hotels Corporation. The Red Lion Family of Hotels formerly operated a website in connection with the domain name <redlion .com> which, according to evidence presented by the Complainant, received over one million visits during the three-month period from November 2023 to January 2024. The Complainant holds trademark registrations for RED LION in multiple jurisdictions, including Chinese registration (October 7, 2005); United States registration (January 15, 2008; and international registration (August 8, 2008) in class 9. The disputed Domain Name was registered by a Chinese Individual on October 25, 2023, and currently resolves to a webpage powered by Shopify e-commerce software but the website has not yet been set up. The Respondent’s contact street address in the Registrar’s WHOIS database is incomplete, as it consists only of a city, province, and postcode.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed Domain Name. The Respondent is not sponsored by, or affiliated with, the Complainant in any way. The Complainant has not given the Respondent permission to use the Complainant’s trademarks in any manner, including in domain names. The Complainant further alleges that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith. There is no plausible good faith reason or logic for the Respondent to have registered the disputed Domain Name. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions. The Complainant had earlier sent cease-and-desist letters in English to the Registrar, addressed to the Respondent.

Held: In the present case, the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2023, years after the registrations of the Complainant’s trademarks, including in China, where the Respondent is based. A simple Internet search reveals that the Complainant is an industrial data company that operates a website in connection with the domain name <redlion .net>. The Complainant provides no evidence of the business, activities, or reputation of this company. Rather, the Complainant seeks to demonstrate the fame of the Red Lion Family of Hotels that formerly operated a website in connection with the domain name <redlion .com>. The Complainant asserts that it (i.e., Red Lion Controls, Inc.) is a subsidiary of the Red Lion Family of Hotels. However, the lack of any apparent relationship between the industrial data business and trademarks of Red Lion Controls, Inc., on one hand, and the evidence regarding the hotels and properties of the Red Lion Family of Hotels, on the other hand, gives the Panel reason to doubt that assertion. While a procedural order might have enabled the Complainant to clarify its identity or substantiate its alleged relationship to the Red Lion Family of Hotels, the Panel considers that such an exercise would be a misallocation of resources due to other problems in the Complaint, due to the following reasons.

The RED LION mark consists of two dictionary words describing a common heraldic emblem. A search for these words in the WIPO Global Brand Database reveals that they are identical to the textual element of many trademarks currently registered in multiple jurisdictions by different parties. A search for the same words through search engines also reveals that there are other entities that have used “red lion” to promote their businesses. These circumstances undermine the Complainant’s assertion that the identity between the disputed Domain Name and its RED LION mark and <redlion .com> domain name demonstrates knowledge of, and familiarity with, the Complainant’s brand and business. Accordingly, even if the Complainant is related to the Red Lion Family of Hotels as it asserts, the Panel cannot infer from the evidence on record that the Respondent had the Complainant or its mark in mind when the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name. Therefore, the evidence on file does not indicate that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark. Nevertheless, the Panel notes that changed circumstances that clearly point to an intention to take unfair advantage of the Complainant’s mark could support grounds for a refiling.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: CSC Digital Brand Services Group AB, Sweden

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response