What’s Going on with the Passive Holding Doctrine?

The Fairmont. Group dispute is more complex and nuanced than it first appears. It raises four questions about how the UDRP is applied.

- Is the passive holding doctrine firmly rooted in the language of the UDRP?

- In a no-response dispute, how is the balance of probabilities determined for the allegation that there is no plausible good faith use for the disputed domain name?

- Does the location of the panelist matter?

- Why is there a recent trend of panelists mischaracterizing the WIPO Overview’s guidance as to passive holding? … continue reading the commentary here.

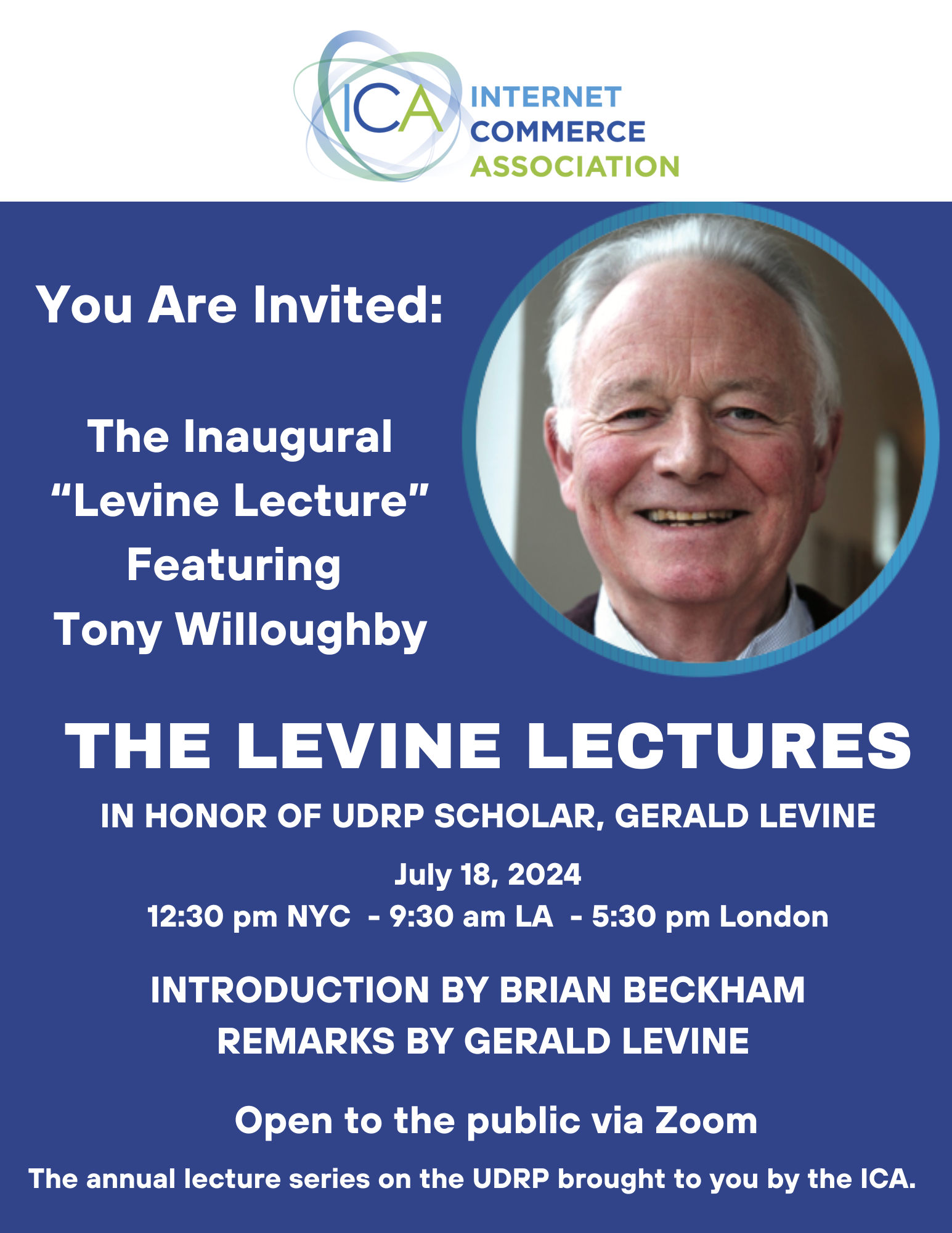

SIGN UP FOR THE INAUGURAL “LEVINE LECTURE” HERE

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 4.21), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ What’s Going on with the Passive Holding Doctrine? (fairmont .group *with commentary)

‣ Not Smart: Complainant Tries to Catch Domain Name Through UDRP Process and Gets RDNH’d (smartcatch .com *with commentary)

‣ Does the Trademark Mean Something Other than a Brand? (elmostrador .com *with commentary)

‣ Dispute Exceeds the Relatively Limited “Cybersquatting” Scope (puntoblum .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel: Respondent ‘Forged Evidence to Support His Clumsy Arguments’ (universalmusicgroup .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Failed to Prove Trademark Rights (twinbeech18 .com *with commentary)

What’s Going on with the Passive Holding Doctrine?

Fairmont Hotel Management L.P. v. Yali, WIPO Case No. D2024-1292

<fairmont .group>

Panelist: Mr. Saisunder Nedungal Vidhya Bhaskar

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a luxury hotel brand owned by Accor Group established in 1907 and it has been operating 81 hotels spread across 27 countries, offering luxurious room and dining experience commonly known by the name “Fairmont” in the hospitality industry. The Complainant is the registered proprietor of the mark FAIRMONT in the United States registered on April 16, 2002, on December 10, 2002, and on August 23, 2016, respectively. The Complainant along with its parent company operates the domain <fairmont .com> registered on August 31, 1995. The disputed Domain Name was registered on March 6, 2024, and does not currently resolve to an active website, but at the time of the Complaint, it had resolved to a landing website in which the disputed Domain name was offered for sale. The Complainant alleges that its trademark is world renowned, and the Respondent could simply not have chosen the disputed Domain Name for any reason other than to deliberately cause confusion amongst Internet users as to its source to take unfair advantage of the Complainant’s reputation. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions.

Held: In the light of the well-known status of the trademark of the Complainant and the fact that the Respondent has incorporated the trademark in entirety in the disputed Domain Name which is not active but merely a passive holding in order to unduly enrich himself, the Panel is in no doubt that the Respondent had the Complainant and its rights in the FAIRMONT mark in mind when it registered the disputed Domain Name. Accordingly, in Panel’s view the bad faith is evidently established where a disputed Domain Name is so obviously connected to the well-known trademark and hence its very use by the Respondent with no connection to the trademarks suggests opportunistic bad faith.

Having reviewed the available record, the Panel finds the non-use of the disputed Domain Name does not prevent a finding of bad faith in the circumstances of this proceeding. Although panelists will look at the totality of the circumstances in each case, factors that have been considered relevant in applying the passive holding doctrine include: (i) the degree of distinctiveness or reputation of the complainant’s mark, (ii) the failure of the respondent to submit a response or to provide any evidence of actual or contemplated good-faith use, and (iii) the respondent’s concealing its identity or use of false contact details (noted to be in breach of its registration agreement), see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.3. Having reviewed the available record, the Panel notes the reputation of the Complainant’s trademark globally, and the composition of the disputed Domain Name which incorporates the trademark in entirety, the failure of the Respondent to submit a response and finds that in the circumstances of this case the passive holding of the disputed Domain Name does not prevent a finding of bad faith under the Policy. Based on the above findings and in the absence of any response from the Respondent, the Panel finds that the Complainant has established the third element of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainant’s Counsel: Dreyfus & associés, France

Respondent’s Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA Director, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

The Fairmont. Group dispute is more complex and nuanced than it first appears. It raises four questions about how the UDRP is applied.

- Is the passive holding doctrine firmly rooted in the language of the UDRP?

- In a no-response dispute, how is the balance of probabilities determined for the allegation that there is no plausible good faith use for the disputed domain name?

- Does the location of the panelist matter?

- Why is there a recent trend of panelists mischaracterizing the WIPO Overview’s guidance as to passive holding?

The history of UDRP jurisprudence shows that some panelists have attempted, at times successfully, to effectively modify, rewrite, or ignore the actual language of the Policy to expand its scope. UDRP Digest comments on the fuck3cx.com case and the wynncruelty.com case describe how an early UDRP decision succeeded in effectively eliminating “confusing” from the Policy’s requirement that a disputed domain name must be identical or have “confusing similarity” to the Complainant’s mark to satisfy the first element of the Policy. This led to expanding the scope of the Policy to cover domain names that were merely similar rather than confusingly similar.

In another instance, 10-years into the UDRP, a group of panelists threw UDRP jurisprudence into turmoil and encouraged a surge in baseless complaints by pushing what became known as the Theory of Retroactive Bad Faith (RBF). RBF attempted to expand the scope of the Policy to cover domain names that were registered in good faith by eliminating the requirement that registration in bad faith must be demonstrated as an essential element of a decision to transfer a domain name. Fortunately, after several years of disruption, the views of more responsible panelists ultimately prevailed, and RBF was discredited. Yet that the attempt was nearly successful demonstrates again that some panelists (mis)use their discretion to expand the scope of the Policy. This story is told in an article by me and Zak Muscovitch entitled “The Rise and Fall of the UDRP Theory of ‘Retroactive Bad Faith’”.

Yet another instance of panelists attempting to expand the scope of the UDRP was entirely successful. The seminal decision is commonly referred to as Telstra. Telstra declared that under certain circumstances, the scope of the Policy can be expanded by asserting that “non-use” nevertheless can meet the definition of use. This approach is now nearly universally adopted by other panelists and Telstra is one of the most cited of all UDRP decisions.

Not Smart: Complainant Tries to Catch Domain Name Through UDRP Process and Gets RDNH’d

SMARTCATCH v. Domain, Administrator, NameFind LLC, WIPO Case No. D2024-0544

<smartcatch .com>

Panelists: Mr. Steven A. Maier (Presiding), Ms. Christiane Féral-Schuhl and Mr. Nick J. Gardner

Brief Facts: The French Complainant, founded in September 2016, is a company registered in France. It is a university spin-off enterprise with activities based on the development and production of capture devices for circulating biomarkers in the health field. The Complainant is the owner of two French trademarks for the SMARTCATCH, word mark (February 3, 2017) and figurative mark (March 12, 2021); and also an International trademark for a figurative mark SMARTCATCH (December 20, 2023). The Complainant operates a website at <smartcatch .fr>. The Complainant submits that the disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent on May 9, 2023 (“Updated Date” returned by a WhoIs search). The disputed Domain Name was acquired by the Respondent on December 21, 2015 and resolves to a webpage indicating that the disputed Domain Name is for sale, and including what appear to be PPC links to third-party advertisers.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not operate its business under the name SMARTCATCH, nor is there any evidence that it intends to use the disputed Domain Name for its business, rather the disputed Domain Name has been offered for sale by the Registrar at an excessive price of USD $8,385.82. The Respondent contends that it is a distinguished reseller of generic domain names and acquired the disputed Domain Name in the course of that business. It also contends that the terms “smartcatch” or “smart catch” are common phrases in the English language and are not exclusively referable to the Complainant. The Respondent further submits that the PPC links on its website have been consistent with the semantic understanding of the phrase “smart catch”, having included cell phone accessories and other goods or services having no relevance to the Complainant’s activities. The Respondent finally contends that the Complainant is seeking a “free upgrade” of its French domain name by making false and unsubstantiated claims and by using the Policy as a tool to attempt to wrest the disputed Domain Name from its lawful owner.

Held: The Panel finds in this case that the mark SMARTCATCH is comprised of two dictionary words, “smart” and “catch”, and that, even in combination, the terms “smartcatch” or “smart catch” have been used in commerce by a variety of different parties. Aside from the third-party trademark registrations identified by the Respondent, a simple Google search of the term “smartcatch” produces results relating to, for example, fishing technology, food preparation and insect control. The Panel also finds that the Complainant has failed to provide any substantial evidence of its business profile or activities that could give rise to an inference that the Respondent had the Complainant’s trademark in mind when it registered the disputed Domain Name. Indeed, the Panel finds such circumstances to be impossible in this case, since the Respondent has provided evidence that it acquired the disputed Domain Name in December 2015, some four months before the date of the Complainant’s first trademark application and nine months before it submits it came into existence. The Panel finds in these circumstances that the Complainant has failed to establish that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the disputed Domain Name.

Most significantly, since the Complainant has been unable to establish any existing trademark rights at the date the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name (the original 2004 creation date being irrelevant), the Complainant cannot establish that the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith and the Complainant must fail on that ground (see section 3.8.1 of WIPO Overview 3.0). The Complainant has also been unable to establish that the Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name, to redirect to PPC links and/or to offer it for sale, is indicative of bad faith on the Respondent’s part. The Respondent has made a credible case that it did not register the disputed Domain Name to take unfair advantage of the Complainant’s trademark rights. In circumstances where the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name otherwise than in bad faith, the UDRP does not prevent it from subsequently offering the disputed Domain Name for sale at such price as it may see fit.

RDNH: In this case, the Complainant incorrectly submitted that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on May 9, 2023, when it had in fact acquired the disputed Domain Name on December 21, 2015, being several months before the Complainant even claims to have acquired any relevant trademark rights. While this submission could be viewed as a mistake, the Complainant is legally represented in this case and should have been aware that its Complaint could not succeed in circumstances where the disputed Domain Name was registered before it acquired any relevant trademark rights. The Complainant should similarly have known that the “Updated Date” in a WHOIS search does not by itself establish a transfer of ownership. Further, even if the Complainant was mistaken as to the registration date of the disputed Domain Name, it provides no evidence of its business profile or trading activities that might enable the Panel even to infer that the Respondent was at any material time aware of its SMARTCATCH trademark and has sought to profit unfairly from its reputation attaching to that trademark.

Finally, the Complainant volunteers in its Complaint that it plans to expand its activities in the United States, is already working on this project, and that the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name is therefore prejudicial to its activities. In circumstances where the Complaint had no reasonable prospect of success under the terms of the Policy, the Panel accepts the Respondent’s contention that the Complainant is likely to have brought this proceeding in the hope of securing a transfer of the disputed Domain Name without having to pay the advertised asking price. The Panel, therefore, finds that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Selarl Oriamedia, France

Respondents’ Counsel: Levine Samuel, LLP, United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: According to the Complainant itself, the Domain Name had been offered for sale at a price of USD $8,385.82 “which it contends is particularly high and exceeds a normal price”. This is truly remarkable because it means that the Complainant passed up an opportunity to purchase the Domain Name for a reasonable and relatively low sum, but instead embarked upon a UDRP at costs likely approaching this sum and ended up RDNH’d to boot. The Complainant’s share of the Provider’s fees for the three-member Panel were USD $2,000 plus legal fees payable to its counsel though unknown, would not be surprising if they were in the USD $5,000 range. That’s an estimated $7,000 already. For an estimated $1,385.82 more, the Complainant could have purchased itself a very nice Domain Name and avoided the embarrassment of a RDNH finding against it. What a shame. Now the Complainant is likely facing a significantly steeper price from the Respondent who will likely want to recover its own legal fees and costs and will likely drive a harder bargain after being subjected to an abusive UDRP Complaint.

Does the Trademark Mean Something Other than a Brand?

La Plaza S.A. v. Reserved for Customers, MustNeed .com, WIPO Case No. D2024-1256

<elmostrador .com>

Panelist: Mr. Matthew Kennedy

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the publisher of an online newspaper from Chile titled “El Mostrador” launched on March 1, 2000. The Complainant owns Chilean trademarks, registered on July 28, 2000 and on November 30, 2017 respectively. The Complainant also registered the domain name <elmostrador .cl> on March 1, 2005 that it uses in connection with a website where it publishes its newspaper. The disputed Domain Name was created on October 14, 2002 by a Chinese Respondent. According to archived screenshots presented by the Complainant, as of June 8, 2022, it resolved to a landing page displaying the disputed Domain Name against a background image of moai (the famous stone statues on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in Chile). Below this, the landing page displayed Pay-Per-Click (“PPC”) links that were all in Spanish and mostly related to real estate, as well as Chile news, used cars in Chile, and houses for sale in Puerto Montt (a town in Chile). Many of the links directed to websites related to Chile, including digital newspapers in that country. As of February 21, 2024, the landing page displayed a banner in English reading “This domain name might be for sale!!! Contact to check it out!” with no image.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is perfectly aware of the Complainant, which is one of the most relevant and prestigious media outlets in Chile. The site associated with the disputed Domain Name contains news, which is the very type of service that the Complainant provides, and it displays content related to Chile, which reveals complete awareness that the disputed Domain Name corresponds to a famous and well-known expression in Chile. The Complainant further alleges that he holds prior trademark and domain name registrations of EL MOSTRADOR, which is sufficient to demonstrate prima-facie that the Respondent knew of its existence, especially considering that the Respondent uses the same name to publish news and advertising regarding Chile, where the Complainant operates. EL MOSTRADOR is a famous trademark in Chile and abroad. The Respondent objected repeatedly to the language in which the Complaint was filed and did not otherwise reply to the Complainant’s contentions.

Held: In the present case, the disputed Domain Name was registered in 2002, after the original registration of the Complainant’s EL MOSTRADOR mark in 2000. Although the disputed Domain Name is identical to the mark, the Panel notes that the mark consists of an ordinary Spanish dictionary word meaning “counter” (as in a shop counter) preceded by the definite article. It is not difficult to imagine potential commercial uses for that name. In the circumstances, the Panel does not consider that the Respondent should be deemed to have constructive notice of the contents of the Chilean trademark register. The Complainant asserts that its online newspaper was launched in 2000 but, according to its evidence, it registered the domain name associated with its online newspaper in 2005, three years after the registration of the disputed Domain Name, and it registered its other mostrador-formative domain names later still.

While the Complainant may be “one of the most relevant and prestigious media outlets in Chile” today, nothing on the record indicates that this was true at the time when the disputed Domain Name was registered and, even if it were, that alone would not give rise to the inference that the Respondent, which is based in China, was aware of the Complainant because there is a plausible alternative explanation for the registration of the disputed Domain Name (i.e., its dictionary meaning). While the Complainant shows that the landing page associated with the disputed Domain Name formerly displayed a Chilean-themed image, and that it continues to display PPC links related to Chile (including Chile news), this evidence dates from 2022 and 2024 and does not shed light on the Respondent’s aim when it registered the disputed Domain Name. Nor is there any evidence of the Respondent’s registration or use of other domain names that might establish a pattern of bad faith.

Accordingly, the evidence presented does not indicate that it is more likely than not that the Respondent’s aim in registering the disputed Domain Name was to profit from or exploit the Complainant’s trademark. Given that the Panel has not found that the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith, it is unnecessary to consider whether it is being used in bad faith.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Gonzalo Sánchez Serrano, Chile

Respondents’ Counsel: Irene Wang, China

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: The Panelist made several important and nuanced determinations in this case that are worthy of mention.

1. The Panel took the crucial preliminary step of evaluating the nature and potential meaning of the Domain Name, whether or not this is explicitly referenced by the Complainant. I suggested this approach in my recent case comment on the mutti .com case:

“A Panelist might have taken note of the nature of the Domain Name as a result of the Complainant’s own admission; it is a surname corresponding to the surname of the Complainant’s founders. As such, it is conceivable that the Domain Name was registered because it corresponds to a surname rather than a highly distinctive term necessarily and exclusively associated with the Complainant’s brand.

Even beyond that obvious fact however, a short and pronounceable term like this should generally cue Panelists to the possibility that it could also possibly have a meaning in another language.

A Panelist, particularly in an undefended case, could in such circumstances use Google translate to automatically detect if such a meaning exists in any language. When I did so, it was instantly apparent that “mutti” means mother in German. Alternatively, a Panel may issue a procedural order inquiring of the Complainant if the trademark has any meaning in a foreign language.”

In the present case, whether or not the Complainant expressly mentioned that EL MOSTRADOR means “the counter” in Spanish (and it likely did not), it was incumbent upon the Panelist to determine whether it had a meaning, as the Panel astutely did. Sometimes a domain name will appear to be a coined term or particularly distinctive, yet a search or a translation will reveal that it is a common term. At other times, it will be obvious that it is a coined term and the Panel need not undertake a preliminary appraisal of whether or not the term has a common meaning. Here, the trademark was obviously in Spanish and accordingly the Panelist referenced a Spanish dictionary to determine the meaning. The fact that the term has a common meaning inevitably colours the dispute and the Panelist then properly takes this into account, particularly in undefended cases.

2. The Panelist properly judged the reputation of the Complainant’s mark not as of the time of filing the UDRP, but rather as of the time that the Domain Name was registered: “While the Complainant may be ‘one of the most relevant and prestigious media outlets in Chile’ today, nothing on the record indicates that this was true at the time when the disputed domain name was registered”. Given that the question is ‘whether the Respondent had the Complainant in mind when registering the Domain Name’ it is a crucial distinction for a Panelist to make since a Complainant’s current reputation may be greater than it was many years ago when the Domain Name was registered.

3. The Panelist considered the plausibility of a good faith use for the Domain Name. As noted in the above comment by Nat Cohen on the Fairmont .group case, when it comes to passive or non-use of a disputed domain name, a Panelist must be faithful to the Telstra principle that for there to be imputed bad faith there must be no plausible explanation for the registration. Here, given the meaning of the term, “the counter”, and given the apparent absence of evidence establishing a substantial reputation at the time of Domain Name registration, the Panel concluded that “there is a plausible alternative explanation for the registration of the disputed domain name (i.e., its dictionary meaning)”. Had the Panelist in the Fairmont case undertaken a similar preliminary inquiry, i.e. determining whether “Fairmont” has any plausible alternative uses, the outcome would have been different in that case.

4. The Panelist noted that despite recent evidence of potential bad faith use such as PPC links related to the country of origin of the Complainant’s newspaper and given the Chilean-themed imagery on the associated website, this evidence “does not shed light on the Respondent’s aim when it registered the disputed domain name” apparently back in 2002. This too is an important and nuanced distinction embraced by the Panelist, because once again, ‘the question is what was in the mind of the Respondent at the time of registration’, not now.

Dispute Exceeds the Relatively Limited “Cybersquatting” Scope

Julius Blum GmbH v. Galimberti Ferramenta Snc, WIPO Case No. D2024-0943

<puntoblum .com>

Panelist: Ms. Marina Perraki

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded more than 70 years ago, is active in furniture fittings. It has production facilities in Austria, Poland, the United States of America, Brazil and China as well as 33 subsidiaries and representative offices globally. The Complainant owns several trademark registrations for BLUM, including the European Union trademark (registered on June 2, 1998). The disputed Domain Name was registered on January 23, 2014, and redirects to a website at “eshop .galimbertiferramenta .com/puntoblumcom” which sells different items of several brands, including furniture fittings and furniture accessories of Complainant under the Complainant’s trademark BLUM, as well as of the Complainant alleged competitors. The Complainant alleges that the disputed Domain Name has been designed to imply that there is an affiliation between the Respondent and the Complainant or that the Complainant endorses the Respondent’s activities even though per the Complainant no affiliation between the Respondent and the Complainant or endorsement by the Complainant exists.

The Respondent contends that he has been active in the distribution of hardware, small parts and technical articles for over 80 years and was endorsed with the Punto Blum Reseller status, as it had been doing business with the Complainant for more than twenty years. The Respondent submits a letter from the Complainant’s Italian distributor, dated January 28, 2014, whereby the Complainant’s Italian Distributor expressly authorized the Respondent to make use of the Complainant’s trademark for its website and its catalogues, in accordance with the terms of use of Complainant’s mark. The Respondent further submits an email of April 23, 2014, they sent to a manager of Complainant at the email address “[…]@blum .com” mentioning “I am sending you the provisional link for access to the beta version of our webshop dedicated to the marketing of Blum products puntoblum(.com): 1499” discussing also changes that were requested for the use of Complainant’s mark on the site.

Held: Under this third element of the Policy, the Panel’s only role is to assess whether, on balance, the Respondent acted in bad faith, i.e., that they possessed the relevant negative intent vis-à-vis the Complainant’s trademarks when registering and using the disputed Domain Name. It is not the role of the Panel to assess whether the Respondent has infringed the Complainant’s trademarks or violated any agreement between the two. The Respondent believes they were entitled to register and use the disputed Domain Name and demonstrated that such purported use was communicated to the Complainant (through a person under an email address “@blum .com”, identified by the Respondent as the Complainant’s “market contact for the resale segment in Italy”) and its Italian distributor who thereafter even awarded Respondent with a recognition award of their long collaboration. On the other hand, the Complainant stated that the use was unauthorised however they did not seek to rebut any of the arguments and documents submitted by the Respondent, while there was no explanation in the Complaint about the collaboration with the Respondent.

The Respondent may be right or wrong about their belief from the point of view of trademark infringement – as to which the Panel expresses no view. However, the Panel does not consider that the circumstances are sufficiently clear to enable it to make a finding that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith for the Policy. Moreover, the Panel is concerned that this situation may be one in which there is a dispute between the Complainant and the Respondent that falls outside the scope of the Policy. Panels have tended to deny complaints not on the merits but on the narrow grounds that the dispute between the parties exceeds the relatively limited “cybersquatting” scope of the Policy and would be more appropriately addressed by a court of competent jurisdiction or perhaps in mediation, see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.14.6.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Torggler & Hofmann Patentanwälte GmbH & Co KG, Austria

Respondents’ Counsel: NPA Studio Legale, Italy

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Bookmark this case because the Panelist succinctly and accurately laid out a crucial principle governing the scope of the UDRP, which I will repeat here:

“The Respondent may be right or wrong about their belief from the point of view of trademark infringement – as to which the Panel expresses no view. However, the Panel does not consider that the circumstances are sufficiently clear to enable it to make a finding that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith for the Policy. Moreover, the Panel is concerned that this situation may be one in which there is a dispute between the Complainant and the Respondent that falls outside the scope of the Policy. Panels have tended to deny complaints not on the merits but on the narrow grounds that the dispute between the parties exceeds the relatively limited “cybersquatting” scope of the Policy and would be more appropriately addressed by a court of competent jurisdiction or perhaps in mediation, see WIPO Overview 3.0, section 4.14.6.”

I love how the Panelist said that the “Respondent might be right or wrong… from the point of view of trademark infringement – as to which the Panel expresses no view”. Exactly. An astute Panelist will recognize the limitations of the procedure and not wade into matters for which they have no jurisdiction and are ill-equipped given the nature of UDRP proceedings. Such a circumspect and self-limiting attitude is what is demanded of Panelists. We know you can probably do a good job of deciding trademark infringement cases, but the UDRP does not ask you to do that.

Panel: Respondent ‘Forged Evidence to Support His Clumsy Arguments’

<universalmusicgroup .com>

Panelists: Mr. Gerald M. Levine, Ms. Sandra J. Franklin, and Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith (Chair)

Brief Facts: The Complainant Universal City Studios LLC., is a film production and distribution company, while the other Complainant Universal Music Group N.V. is a music company. The Complainant has rights in the UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP mark based on registration of the mark with the USPTO (registered: January 11, 2011; first use: 1999). The Complainant submits that the disputed Domain Name was previously owned by the Complainant but expired in 2016. The Respondent acquired the Domain Name in 2017 and offers it for sale to the Complainant for various sums including most recently USD $10.5 million. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the Domain Name for any bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use as the Respondent has previously simply redirected the disputed Domain Name to an affiliate of the Complainant. The Respondent also uses an e-mail address connected to the Domain Name to promote his app on the Google Play store and offers the Domain Name for sale for a sum well in excess of any possible out-of-pocket costs.

The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent does not have rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name and any evidence presented by the Respondent otherwise is an obvious forgery. Additionally, the Respondent has engaged in other bad faith conduct, including engaging in a pattern of conduct in registering domain names corresponding to well-known marks. The Respondent contends that the Complainant’s allegations against him are unfounded and that he has legitimate interests in the Domain Name as he participated in a music video at Universal Studios at the age of 13 and was an intern at Universal Records at the age of 17. The Respondent further adds that he acquired the Domain Name for $250,000 from Universal Studios in 2003 and held registered trademark rights in THE UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP with the USPTO. Finally, he is “the holder of a 2% equity stake in Universal Records, as granted by Doug Morris, the former CEO of Universal Records which grants Respondent unequivocal permission to use the name Universal Music Group”.

Held: The Domain Name has variously resolved to a website offering itself for sale or to a website operated by an affiliate of the Complainant. Neither of these uses is sufficient by itself to establish rights or legitimate interests. In addition, Respondent has offered the Domain Name for sale to the Complainant for a sum considerably greater than any likely out-of-pocket costs incurred in registering the Domain Name. Absent any legitimate explanation, the use of a Domain Name in this manner is neither a bona fide offering of goods or services, nor a non-commercial or fair use under the Policy. As noted, the Respondent has made five claims that he states provide a basis for him to establish rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name. The Panel does not accept the Respondent’s claim that the Respondent has presently or ever held trademark rights in the UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP. For the reasons set out in the Complaint, the Panel finds that the evidence submitted by the Respondent in support of this contention to be a series of clumsy and obvious forgeries.

The Panel does not accept the Respondent’s various explanations behind its ownership of the Domain Name and finds that the Respondent acquired the Domain Name for the clear purpose of selling (or otherwise leveraging) the Domain Name to the Complainant or a third party for a for valuable consideration in excess of any out-of-pocket costs. The Respondent has never used the Domain Name for any active purpose and commencing 2017, he engaged in a long-running series of communications with Complainant seeking to sell the disputed Domain Name for a significant price or leverage his ownership for some sort of other commercial benefit.

In the present case, given the nature of the Domain Name, the content of the communications between the Complainant and Respondent and the lack of a plausible and supported alternative explanation provided by Respondent, the Panel finds that the Respondent registered and used the Domain Name in bad faith pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(b)(i).

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Steven M. Levy of FairWinds Partners LLC, District of Columbia, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: This is undoubtedly one of the craziest cases I have seen. The brazenly false allegations and indeed, forged exhibits as found by the Panel, are nearly as comical as they are shocking.

Complainant Failed to Prove Trademark Rights

Textron Aviation Inc. v. Southwestern Aero Exchange, NAF Claim Number: FA2404002094083

<twinbeech18 .com>

Panelist: Mr. Charles A. Kuechenmeister

Brief Facts: The Complainant manufactures and sells airplanes and airplane parts. It claims rights in the BEECHCRAFT mark based upon its registration of that mark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent is not using the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services or for a legitimate non-commercial or fair use but instead uses it to attract internet users to its website where it appears to sell parts of unknown provenance for Complainant’s Beechcraft 18 airplanes. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent registered the domain name with actual knowledge of the Complainant and its rights in the BEECHCRAFT mark, it is using the Domain Name to disrupt the Complainant’s business and attempts to attract Internet users to its website by causing confusion with the Complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship affiliation or endorsement of its website. The Respondent did not submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant alleges that it is the owner of several USPTO registrations of the BEECHCRAFT mark. In support, it submitted a number of TSDR printouts showing that the BEECHCRAFT mark is indeed registered with the USPTO, but none of these printouts lists the current owner of these marks. On May 14, 2024, the Panel issued a Rule 12 Request to the Complainant to submit evidence of its ownership of these registrations, but the Complainant did not respond within the time allowed. There being no evidence of the ownership of the relevant mark, the Complainant has failed to meet the requirements of Policy ¶ 4(a)(i). Accordingly, the relief requested is denied.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Jeremiah A. Pastrick, Indiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: It shouldn’t need to be said, but “Rule No. 1” is parties should respond to Panel Orders! Good golly. Here, the Complainant apparently “submitted a number of TSDR printouts showing that the BEECHCRAFT mark is indeed registered with the USPTO, but none of these printouts lists the current owner of these marks”. The Panel, in an apparent effort to ensure justice by affording the Complainant an opportunity to furnish “evidence of its ownership of these registrations”, the Panel issued a Procedural Order, yet incredibly the Complainant failed to respond within the time allowed. Had the Complainant responded to the Procedural Order, the Complainant would likely have furnished a USPTO extract clearly showing that the Complainant, Textron Aviation Inc. was indeed the registered owner of a live trademark registration for BEECHCRAFT, as it in fact is.