We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (Vol. 3.26), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from Experts. We invite guest commenters to contact us.

‣ Whose Burden is it to Wake Sleeping Evidence? (sleeptopia .com*with commentary)

‣ How Stericycle, Inc. Proved Common Law Rights in “Stericorp”? (stericorp .com*with commentary)

‣ Panel: With “Not a Skerrick of Bad Faith”, Complainant “Resorted to its Worst Possible Argument” (vbg .com*with commentary)

‣ Panel Labels the Complaint as Highly Misleading, in a Matter Involving Confusingly Similar Marks ( and *with commentary)

—

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

Whose Burden is it to Wake Sleeping Evidence?

Sleeptopia, Inc. v. Gregory Perez, WIPO Case No. D2023-1317

<sleeptopia .com>

Panelist: Mr. Christopher S. Gibson

Brief Facts: The Complainant, since 2013, has advertised, promoted, and offered its products and services in the field of sleep apnea using its business name and trademark, SLEEPTOPIA. The Complainant’s products and services are provided and sold under the SLEEPTOPIA mark in physical office locations and through the Complainant’s website at <sleeptopiainc .com>, since February 14, 2013. The Complainant owns a word mark for SLEEPTOPIA before USPTO (registered February 11, 2020; first use in commerce: January 1, 2013). The Domain Name was initially registered on July 30, 2006, and the disputed Domain Name resolves to pay-per-click (“PPC”) links offering products and services that compete with those offered by the Complainant. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name, as the Respondent is merely engaging in cybersquatting activity that uses the Complainant’s SLEEPTOPIA mark to host sponsored PPC links associated with, and directly competing with the Complainant’s products and services.

The Complainant further points out that the disputed Domain Name was “last updated” on September 4, 2022, and hence believes that the disputed Domain Name was likely transferred to the Respondent after the Complainant acquired trademark rights in the SLEEPTOPIA mark. In support of this argument, the Complainant further relies upon the archived images between 2006 and 2021 evidencing the Domain Name previously resolved to a registrar parking page and further that shortly before or around the “last update” date of September 4, 2022, the registrant’s information was removed from publicly accessible WhoIs information, presumably as a result of a transfer in ownership or employment of a proxy service, indicating bad faith. The Complainant argues that as a result, the Policy’s registration in bad faith requirement should be assessed from this date, as the date the current Respondent likely acquired the Domain Name, and as the relevant date of bad faith registration by the Respondent, which post-dates the Complainant’s trademark rights in and ownership of the SLEEPTOPIA mark. The Respondent did not file a Response.

Held: The Respondent neither used the Domain Name for a legitimate noncommercial or fair use nor used it in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. Instead, the Domain Name links to a PPC site with links to products in the sleep therapy industry that are directly competitive with those offered by the Complainant under the SLEEPTOPIA mark, including CPAP supplies, pillows, and mattresses. Additionally, past UDRP panels have established that parking webpages for a respondent’s commercial gain do not provide a legitimate interest in the domain name under the Policy. It is also evident that the Domain Name is being used in bad faith, as it resolves to a webpage with PPC links purporting to offer goods and services competitive with those offered by the Complainant. The Respondent made no attempt to respond to the Complainant’s allegation on this point, or to otherwise justify its use of the Domain Name. That noted, the key question, in this case, is whether the Domain Name was registered in bad faith.

The Complainant argues that the WhoIs registration record was updated on September 4, 2022, after the Complainant had acquired its trademark rights and presents further evidence in support. Faced with the allegations surrounding the updated WHOIS record, the Respondent did not file a response with no attempt at all to explain or justify its registration of the Domain Name, or its subsequent use of the Domain Name. Further, the Respondent has not responded to the Complainant’s allegation that, based on the Complainant’s established, long-term use of SLEEPTOPIA in connection with the Complainant’s products and services and Complainant’s reputable business and goodwill, the Respondent likely had knowledge of the Complainant’s trademark before the relevant September 4, 2022, date, and therefore acquired the disputed Domain Name in bad faith to target the Complainant’s SLEEPTOPIA mark and use it for the PPC website with links to products that directly compete with the Complainant’s products and services. The Panel determines that, on the balance of the probabilities and for all of the above reasons, the Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Hovey Williams LLP, United States

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Special Guest Commentary by Steven M. Levy:

Steve Levy focuses on trademark domain name disputes and has personally researched, drafted, and filed over 600 domain name complaints. Steve is honored to also serve as a Panelist for a number of organizations that offer dispute resolution services under the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) and other dispute policies. He is a frequent speaker on the topic of domain name disputes and is eager to encourage greater awareness of, and participation in this field by stakeholders and practitioners. Prior to his current roles, Mr. Levy led the global intellectual property practice team at the Home Depot, was an associate at the New York office of the Proskauer law firm, and was in-house counsel to Sony Corporation based in Tokyo.

The views expressed herein are Steve’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Steve is not affiliated with the ICA.

Whose Burden Is It to Wake Sleeping Evidence?

This decision raises two very timely and critical issues. First is the sufficiency of the evidence, and how far a panelist itself expected to go to find information that has not been submitted by the parties. The second is why there’s such a low response rate in UDRP cases and how this can lead to decisions based on an incomplete factual record.

First, the Panel here found it “reasonable to infer” that a transfer of the disputed domain name had taken place based on a recent change in the Whois record to a proxy service, and a change in website resolution, at around the same time, from a parked GoDaddy page to a pay-per-click page with links competitive to the Complainant. These two signals may, in some cases, indicate a change in ownership but more definitive evidence is often available. A review of archived Whois records reveals that the named Respondent, Gregory Perez, has held the domain name since at least August of 2008, a significant number of years before the Complainant’s claimed date of first trademark use in 2013. So, should the Complainant have provided this evidence when it filed the Complaint? Its certification states that “the information contained in this Complaint is to the best of the Complainant’s knowledge complete and accurate”. Or should the Panel have exercised its authority, under the UDRP Rules, to conduct its own research and look at the archived Whois records?

This brings up the second issue, and the silent party in this case. Why did the Respondent default and fail to explain that it’s owned the domain since before the existence of the Complainant’s trademark rights? Since it owned the domain name for around 15 years, maybe it failed to update the Whois record to its current email address. Or maybe there’s another problem where the Respondent is deceased or incapacitated, or perhaps the WIPO’s email serving the Complaint got caught in the Respondent’s spam filter or the Respondent thought it was a scam and didn’t open the attachment for fear of malware. In any event, the UDRP ecosystem would likely benefit from better service processes such as a confirmation email from a source that’s known to the Respondent, such as its own Registrar.

The bottom line is that a lack of evidence here caused a decision to be made based on an inference rather than on the actual facts of the case.

How Stericycle, Inc. Proved Common Law Rights in “Stericorp”?

Stericycle, Inc. v. Nanci Nette / Name Management Group, NAF Claim Number: FA2305002045321

<stericorp .com>

Panelist: Mr. Paul M. DeCicco

Brief Facts: The Complainant is the leading provider of medical waste, document destruction, and patient engagement solutions worldwide. It asserts common law rights in the STERICORP mark. The disputed Domain Name redirects to third-party websites that feature either adult-oriented material or other material unrelated to the Complainant. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the at-issue domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use. Rather, the Respondent is deceiving consumers and impersonating the Complainant. The Complainant further alleges that the disputed Domain Name has been associated with malware and often redirects to pornography websites and that the Respondent had actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the STERICORP mark prior to registration of the at-issue domain name. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant shows evidence that the mark STERICORP has acquired secondary meaning through long-term continuous use and promotion of the mark as a source identifier related to medical waste-related business. The Respondent having failed to respond to the Complaint offers no evidence challenging Complainant’s contentions regarding its rights in the STERICORP mark. In light of the foregoing, the Panel concludes that Complainant has acquired sufficient common law rights in the STERICORP mark for the purposes of the Policy. Further, the Respondent uses the at-issue domain name address to randomly redirect internet traffic, presumable for its commercial benefit, to third-party websites that offer different types of content, e.g. sites concerned with pornography, gambling, or credit cards. The Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name in this manner constitutes neither a bona fide offering of goods or services nor a non-commercial or fair use under the Policy.

The Respondent uses the at-issue domain name to randomly redirect internet users to websites featuring adult content as well as to other websites, presumptively for commercial gain. Such use of the disputed Domain Name is disruptive to the Complainant’s business. It demonstrates the Respondent’s bad faith regarding the at-issue domain name as per Policy. Additionally, some random websites accessed via the disputed Domain Name may contain malware, thereby further indicating Respondent’s bad faith registration and use of the at-issue domain name. The Respondent had actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights in the STERICORP mark when it registered the disputed Domain Name, which is evident from the notoriety of the Complainant’s STERICORP trademark and from the Respondent’s use of the domain name to trade off such a mark.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Howard S. Michael of Crowell & Moring LLP, Illinois, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Special Guest Commentary from Igor Motsnyi:

Igor is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal in Belgrade, Serbia, www.motsnyi.com Igor is a UDRP panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy. Igor has been the Panelist and Examiner in over 60 UDRP and URS cases.

The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

How Stericycle, Inc. Proved Common Law Rights in “Stericorp”?

Here we have an interesting situation. Complainant alleged common law rights in the “STERICORP” mark and claimed Respondent deceived consumers and impersonated Complainant. There was no response and the Panel agreed and ordered transfer.

According to <UDRP.tools> Respondent in <stericorp .com>, Nanci Nette, was respondent in numerous previous UDRP cases and most of them resulted in transfer (some of these disputes involved popular marks like “Volvo”, “Intesa” and “Only Fans”).

While this may have affected the outcome (along with Respondent’s default), nevertheless there are more questions in the stericorp case than answers.

What is problematic here, as I verified in my own research, is that Complainant, “Stericycle, Inc”, US, does not seem to have any relationship to the term “Stericorp” that was previously used by a different entity (entities).

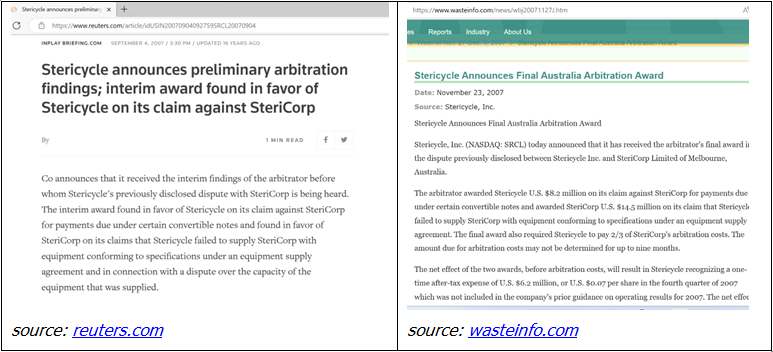

Moreover, there were disputes between “Stericycle” – Complainant and “Stericorp”, Australia and there are numerous online references to the disputes between the two businesses, see e.g.

When I searched for a term “Stericorp”, the first result in both “Google” and “Bing” engines was https://www.stericorp.net/, a website that does not seem to be somehow related to Complainant.

According to the “Whois data” the disputed domain name was registered back in 1999 and was first used by business (businesses) as evidenced by “Wayback machine” not related to Complainant, see e.g.:

Australian website www.delisted.com.au shows that “Stericorp Limited” changed its name to “SteriHealth Ltd” on 07/11/2008, see here. “SteriHealth” is now associated with another Australian business, “Daniels”, see here. It appears that the disputed domain name was abandoned by the previous registrant some years ago and picked up by Respondent.

My own Internet search did not reveal any connection between Complainant and the “Stericorp” mark and any use by Complainant of this mark that could create “common law rights”. Complainant’s own website https://www.stericycle.com/en-us does not have any references to “Stericorp”. The question is how the Panel came to this conclusion: “Complainant shows evidence that STERICORP has acquired secondary meaning through long term continuous use and promotion of the mark as a source identifier related to its medical waste related business”?

We, of course, do not have any access to the record of this case. However, based on the publicly available information, the outcome of this case seems problematic.

It is well accepted that to establish common law rights complainant “must show that its mark has become a distinctive identifier which consumers associate with the complainant’s goods and/or services” (see WIPO Overview 3.0, par. 1.3).

Unfortunately, the decision did not specify what evidence was offered to the Panel and how the Panel came to the conclusion that “Stericorp” became a distinctive identifier associated with Complainant’s goods/services.

What, in my opinion, should be required in cases involving “common law trademarks” is the following narrative:

- Panel should describe evidence offered by complainant in support of its common law rights and

- Panel should also provide a date or a year when such common law rights came into existence (to succeed complainants should prove common law rights pre-date registration date of the disputed domain name).

One of the reasons for making all UDRP decisions public is “to promote the development of a body of persuasive precedents concerning domain name disputes” and that body of precedents would “enhance the predictability of the dispute-resolution system and contribute to the development of a coherent framework for domain names” (see par. 219 of the Final Report of the WIPO Internet Domain Name Process, https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/amc/en/docs/report-final1.pdf).

The point of making UDRP decisions public is also to provide more transparency to UDRP decision making process.

Default cases are no exception and proper reasoning and explanation of issues such as common law rights in UDRP decisions should become a standard.

Panel: With “Not a Skerrick of Bad Faith”, Complainant “Resorted to its Worst Possible Argument”

<vbg .com>

Panelists: The Honorable Neil Anthony Brown KC (Chair), Mr. Petter Rindforthand, and Mr. Jeffrey J. Neuman

Brief Facts: The US Complainant is engaged in providing services designed to help veterans navigate the Veterans Affairs disability claims process. The Complainant claims strong common law rights to the VBG mark through acquired distinctiveness, goodwill, and renown among consumers, since at least 2019. The Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on June 24, 2001. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services, rather the Respondent offers to sell the disputed Domain Name for an “exorbitant six-figure sums” at a price far exceeding its out-of-pocket costs. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent continued to renew the disputed Domain Name after the Respondent had actual knowledge of the Complainant’s mark and therefore retrospectively registered and used the Domain Name in bad faith.

The Complainant initiated an offer to attempt to purchase the disputed Domain Name prior to the initiation of this proceeding. The Respondent contends that he buys, sells, and monetizes generic and common domain names. The domain name is a valuable non-distinctive three-letter acronym which may be identified as standing for many things and as potentially being of use for many purposes. The Respondent further contends that the offer for sale is part of its legitimate business of buying generic domain names to resell at a later date and the Respondent’s offer of a valuable three-letter acronym domain name for sale constitutes a bona fide offering of goods and services. Finally, the Complaint is abusive despite clear notice that the Complainant had to the effect that its claim is frivolous and constitutes Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Held: The Complainant neither submits a registered trademark nor provides evidence in support of its assertions of strong common law rights. The Panel has taken up the invitation to inspect the Complainant’s website. However, having done so, the Panel’s conclusion is that the Complainant’s website does not show that the Complainant markets itself in any real or substantial sense using the term VBG and certainly not that it has done so consistently or regularly. In fact, if it has done so at all, which is itself very doubtful, it has been done only very recently. The Complainant also relies on other material to show its common law trademark, which is sparse in number, are virtually all used merely as an abbreviation and is often used in tandem with the full name of the organization, Veteran Benefits Guide, and most importantly for present purposes, they are not being used to identify the Complainant as the provider of specific goods and services. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not shown by persuasive evidence that it has or has ever had common law or unregistered trademark rights in VBG or in any mark that is relevant to this proceeding.

The Respondent on the evidence registered the Domain Name as part of a legitimate business of buying and selling domain names that he has conducted since the year 2010. That again is consistent with the legitimacy of the Respondent’s acquiring the domain name. Indeed, the notion that running a business registering and selling domain names has been recognized by prior UDRP panels as capable of establishing rights or legitimate interests under the Policy, provided the domain name was not registered to profit from and exploit a complainant’s trademark. In fact, when the Respondent registered the Domain Name, the Complainant did not even exist and was not to come into existence for several years. It is therefore illogical to suggest that the Respondent could have had any actual or even constructive knowledge of any such trademark. There is also no evidence or logic to support that the Respondent actually acquired and renewed the domain name with the intention of selling it to the Complainant.

Moreover, the evidence does not suggest that any such intention was or could have been formed. The Respondent bought the domain name as part of its stock in trade and was thereafter available for purchase by the Respondent or anyone else at any price that could be agreed upon. There is not a skerrick of bad faith revealed by an analysis of that process. The Complainant then surprisingly resorted to its worst possible argument that the registration of the domain name, which the Complainant seems to acknowledge was in “good faith”, was renewed and transformed into a retrospective bad faith registration. To so decide would be in plain contradiction of what a complainant is obliged to prove under the Policy, namely bad faith registration and use. In any event, there is no evidence to support such a conclusion or for the baseless allegation that to try to effect a sale in such circumstances is some form of a “ransom demand”. The Panel, therefore, does not accede to any of the grounds on which the Complainant contends that the Respondent registered and used the domain name in bad faith.

RDNH: The proceeding was brought and pursued when there was no reasonable prospect of it succeeding, as it was always clear that the Complainant could not prove any of the three elements that it was required to prove and to proceed with such a complaint is harassment and in bad faith. The Respondent was entitled to know precisely the trademark that the Complainant relied on, yet it asserted a conflicting and confusing series of alleged trademarks which must have been confusing to the Respondent and was certainly confusing to the Panel. Those alleged trademarks were misspelt several times, showing an apparent indifference to their accuracy. Nor is this a de minimis issue, as the Respondent was entitled to know, in a jurisdiction where the delineation of the trademark is pivotal, exactly what was being alleged against it. Moreover, on several occasions, the Complainant accused the Respondent of bad faith, a serious allegation for which there was never any evidence.

In defending what was essentially a baseless case, the Respondent must have been put to considerable time, trouble and cost in a jurisdiction where there is no provision for legal costs to be awarded to a successful respondent, which the Panel would have ordered, had it had the power to do so. The Complainant’s advisers furnished on two occasions, in the Complaint and the Amended Complaint, certificates that the material it was submitting was “complete and accurate” when the initial proposal by the Complainant to buy the domain name was not disclosed and hence the Complaint and the Amended Complaint were neither complete nor accurate. The Panel, therefore, declares that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Timothy Getzoff of Holland & Hart LLP, Colorado, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: John Berryhill, Ph.d. esq., Pennsylvania, USA

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

This decision is particularly well-written by the Panel led by Neil Brown and assisted by Petter Rindforth and Jeffrey Neuman. Undoubtedly the Response by John Berryhill provided a witty and devastating basis for the Panel’s compelling analysis and conclusions.

Although this case provides a monumental object lesson in the pitfalls that the UDRP presents for unwary Complainants and the corresponding frustrations for unfortunate Respondents, I will focus on one minor yet notable aspect of the decision.

Amongst a litany of reasons why this Complaint was deserving of RDNH, the Panel notably stated inter alia that: “in defending what was essentially a baseless case, the Respondent must have been put to considerable time, trouble and cost in a jurisdiction where there is no provision for legal costs to be awarded to a successful respondent, which the Panel would have ordered, had it had power to do so”. [emphasis added]

The Panel was pointing out that of course, in the UDRP there is no provision for an innocent Respondent victimized by an abusive Complaint, to be awarded costs, but had there been such a provision the Panel would have ordered costs against the Complainant.

Respondents have long argued that there should be a cost sanction for RDNH. When this argument is raised, Complainants will often state that ‘if that is to be the case, then Complainants should be entitled to costs against cybersquatters’. After all, it is argued, both are engaged in misconduct and one is no worse than the other. Domain name investors who usually win most of their cases would surely be in favor of such an “even-handed” approach since they would only very rarely be on the ‘paying end’ of a costs award. This approach would however, be considered unsatisfactory by some Complainants who would say that in practice, Respondents who received an order for an award of costs would more likely be able to collect them from a Complainant than vice versa, since the chances collecting a cost award from a cybersquatter is, as one lawyer I worked for used to say, “Slim to none, and Slim has left town”. Some Complainants therefore suggest that the solution is to have Respondents post a bond with the provider or registrar. This of course is a non-starter, since not only would there be major access to justice issues if Respondents had to post a bond just to be able to defend themselves, but creating a regime for holding onto funds in escrow adds a whole layer of cost and complexity to the system that no one should want nor is anyone really willing to assume, least of all providers and registrars.

Yet the fairness and utility of imposing costs nevertheless remains a very natural reaction amongst some Respondents when it comes to RDNH. One argument previously raised by John Berryhill on this subject, is that ‘we expect cyber-squatters to act this way but we don’t expect lawyers to’, thereby justifying the disparate treatment when it comes to awarding costs for RDNH but not against cyber-squatters. Ultimately however, the political and practical concerns of such a regime seem in my view to make RDNH costs, a remote possibility despite their theoretical attractiveness and appropriateness. Moreover, I believe the most important policy objective is not to find a way of imposing greater penalties for RDNH, but rather finding a way to decrease such instances if not eliminate them altogether, via improved guidance and education for Complaint filers.

Panel Labels the Complaint as Highly Misleading, in a Matter Involving Confusingly Similar Marks

GORAN-TEE Grosshandel GmbH&Co.KG v. Dinesh Deheragoda, MAPLE LEAF GIDA LTD, WIPO Case No. D2023-1001

<mevlanaceylontea .com> and <mevlanatea .com>

Panelist: Mr. Warwick A. Rothnie

Brief Facts: The Complainant and the First Respondent (or rather his company, Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd) produce and distribute tea. The Second Respondent also distributes tea. The Complainant promotes its products from the websites to which the domain names <mevlanacay .com> (2012), <mevlanacay .com .tr> (2020), <mevlanacay .de> (2018), and <goran-tee .de> (2017) resolve. According to the Complaint, the Complainant claims to have built up a substantial reputation in what it calls its “MEVLANA TEA-Mevlana Çay” trademarks. This is disputed by the Respondents. Apart from claiming it has been using its trademarks since before 2003, the Complaint does not include evidence of sales revenues or advertising and promotional expenditures. It provides a link to its websites but does not include details about the volume of traffic to its websites. The Complainant is the owner of a figurative “EUTM” (registered on August 10, 2004), as provided below (on the left):

The second disputed domain name was registered on November 30, 2016. The first disputed domain name was registered on January 24, 2020. Both disputed domain names resolve to websites which very closely resemble each other and promote the sale of “Mevlana Pure Ceylon Tea”. The packaging of the 1000g product shown on both websites is as above (on the right). The most notable difference between the websites is that the “Contact” page for the first disputed domain name provides contact details for the First Respondent while the “Contact” page for the second disputed domain name provides contact details for Mr. Hamid Yusufov.

Both these gentlemen were the founding directors and shareholders of Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd which, from the corporate records provided by the Second Respondent, was incorporated in Sri Lanka in February 2017. Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd promotes its products with the Ceylon Tea Symbol of Quality which is a certification or endorsement scheme operated by the Sri Lanka Tea Board. In March 2022, Mr. Yusufov transferred his shares in Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd to other parties and now operates through the Second Respondent. In its Response, it is stated that the Second Respondent distributes tea throughout the Commonwealth of Independent States (“CIS states”). As noted above, however, the Second Respondent’s website does not appear so limited. The Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd is the owner of registered trademarks in Germany and Switzerland for ‘Mevlana Pure Ceylon Tea’.

Held: There is no evidence before the Panel, however, of how the First Respondent and Mr. Yusufov settled on that particular name. Bearing in mind that neither the Complainant nor the Respondents have suggested that “mevlana” is a dictionary word, a geographical name or otherwise has a commonly accepted generic meaning in relation to tea, therefore, the Panel is not prepared to accept that the First Respondent and Mr. Yusufov adopted the company name in good faith in the absence of such evidence and an understanding of how the name was derived. The disputed Domain Names are being used for commercial purposes to promote Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd’s products, not the Complainant’s products. However, the First Respondent’s company, Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd, and its related company have a number of registered trademarks featuring the word “Mevlana”. Accordingly, the First Respondent’s company appears to have a legal right to sell its tea in at least Switzerland, New Zealand and Norway under that trademark.

The Complaint relies upon the decision in GORAN-TEE Grosshandel GmbH&Co.KG v. Prasad Jayarathna, WIPO Case No. DCH2021-0025, however that decision does not assist the Complainant in this case. Further, given the First Respondent’s position as a shareholder and director of Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd, therefore, the Panel considers the First Respondent has demonstrated rights to use the first disputed Domain Name in connection with the sale of tea in at least those countries. The Panel acknowledges that the website to which the first disputed Domain Name resolves does not appear to be limited to promoting Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd’s products in those countries. However, as the Complainant has demonstrated rights in a registered trademark in the European Union and (through the unopposed decision in GORAN-TEE Grosshandel GmbH&Co.KG v. Prasad Jayarathna, supra.) in Switzerland only, the Panel would not be prepared to infer that Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd’s rights are limited only to Switzerland, New Zealand and Norway.

Accordingly, the use of the first disputed Domain Name in connection with the sale and promotion of Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd’s products in the European Union (if there is such use) or other jurisdictions is more appropriately dealt with through the laws of trademark infringement and unfair competition or passing off. Similarly, if there is a dispute between the parties over who has the right to use the various trademarks in Switzerland, which is more appropriately dealt with in the courts and tribunals having jurisdiction in Switzerland in such matters. Correspondingly, the Panel considers the Second Respondent’s role as a distributor or licensee of Mevlana Ceylon Tea (Pvt) Ltd’s products and also gives it rights to the second disputed Domain Name. In these circumstances, the Complainant is unable to establish that either the Respondent does not have rights or legitimate interests in their respective disputed domain names.

RDNH: The Panel notes that the Complainant, represented by legal counsel, knew about the trademark registrations owned by companies associated with and controlled by the First Respondent. If it did not, the Panel considers it should certainly have investigated and known before filing the Complaint. The existence of the trademark registrations by the companies owned and controlled by the First Respondent for tea in International Class 30 means that the Complainant should have realized it could not succeed. Most importantly, however, the failure to disclose the existence of the trademark registrations owned by the First Respondent’s companies at the very least was highly misleading and, if not corrected by the First Respondent, could very well have resulted in orders that the disputed Domain Names be transferred or cancelled. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: June Intellectual Property Services Inc., Türkiye

Respondents’ Counsel: Tigges Rechtsanwälte, Germany and Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Interestingly in this case, RDNH was found against the Complainant for good reason as well explained by Panelist Rothnie, yet one of the Respondents was not represented. As such, even if there were a costs regime for RDNH, a Respondent who did not elect a three-member Panel and who did not retain counsel, likely would not even be eligible for a costs award as the Respondent did not incur any “costs” per se. This is yet another consideration for those weighing the practicalities of a costs regime.