Ultra Premium Two-Letter .COM Recovered in Theft Case

Two-letter .com domain names like PV .com are extraordinarily valuable and sought after. They are the ultra-luxury real estate of the domain name space. Think, Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, the Peak in Hong Kong, and Belgravia in London. Just last week, the ultra-premium domain name, VT.com sold for USD $2.5 million.

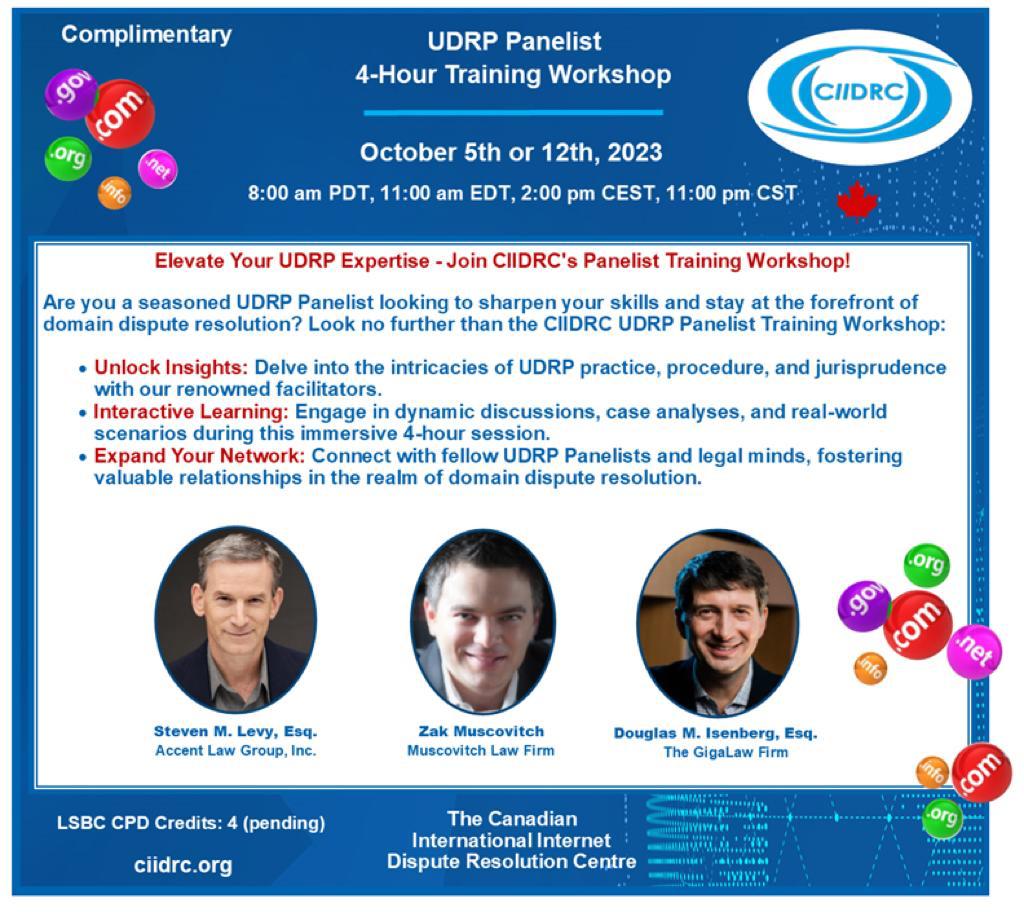

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 3.35), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from experts. (We invite guest commenters to contact us.)

‣ Ultra Premium Two-Letter .COM Recovered in Theft Case (pv .com and packetvideo .com *with commentary)

‣ Domain Investor Shows How to Win a Fanciful Domain Name Case (plasticol .com *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Failed to Establish Common Law Trademark (thewarroom .ag *with commentary)

‣ Is Scoop Soldier Descriptive of Services? (scoopsoldier .com)

‣ Nominative Fair Use (lsatbyfisch .com)

—–

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

The ICA will attend the Domain Days Dubai meeting Nov 1-2, 2023. This is one-of-a-kind event in the MENA region’s domain industry. The conference brings together a diverse crowd of Domain Investors, Registrars, Registries, Monetization & Traffic, Web 3.0 Domains, Hosting & Cloud Providers, SaaS providers, and Industry Enthusiasts.

Kamila Sekiewicz, Zak Muscovitch, and Ankur Raheja will be representing the ICA. We’d love to meet with any members of our UDRP Digest community attending, so please get in touch if you have plans to be there.

Ultra Premium Two-Letter .COM Recovered in Theft Case

PacketVideo Corporation v. PacketVideo Corporation, WIPO Case No. D2023-2702

<pv .com> and <packetvideo .com>

Panelist: Mr. Georges Nahitchevansky

Brief Facts: The Complainant maintains that it is a well-known San Diego-based company and claims rights in the names and marks PV and PACKETVIDEO by virtue of its United States trademark registrations for, and use since 1998. The Complainant appears to have owned and used the disputed Domain Names in connection with a website at some point in time, although it is not clear when the use occurred and for how long. In March 2023, the Complainant lost control of the disputed Domain Names, when a hacker gained “complete access and control over the disputed Domain Names.” The current WhoIs records for the disputed Domain Names show them as registered under the name PacketVideo Corporation with a Tokyo, Japan address. The disputed Domain Names currently do not resolve to an active website or page.

The Complainant contacted the Registrar regarding its loss of control over the domain names in March 2023 and a few days later, the Complainant received an email from an unknown individual asserting he was a hacker and requested the payment of “[USD]17,000 in Bitcoin”. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests and that the Respondent has registered and used the disputed Domain Names in bad faith given that the Respondent “hacked the disputed Domain Names primarily for the purpose of demanding payment from the complainant” or to otherwise improperly profit from them.

Held: While the Complainant may have failed to prove that its PACKETVIDEO or PV marks are famous, enjoy wide recognition, or have become distinctive, this does not mean that the Complainant does not enjoy rights in PACKETVIDEO or PV sufficient for purposes of the Policy. Complainant owns rights in PV as part of a logo trademark registration in the United States, without any disclaimer. In addition, Complainant has produced some evidence of the use of PACKETVIDEO and PV in social media on a LinkedIn page. Moreover, the fact that the Respondent, who appears to be an unknown hacker, chose to target the Complainant supports the notion that the Complainant enjoyed some rights in PACKETVIDEO and PV, otherwise, the Complainant might have not been a target.

The Respondent’s email to the Complainant in March 2023 makes clear that prior to the hacking, the Complainant had been using the disputed Domain Names for emails and other purposes and also the fact that the WhoIs records use the Complainant’s name as the registrant. In all, although there are significant questions regarding the strength of the Complainant’s claimed rights in PACKETVIDEO and PV, the Panel based on the foregoing is prepared to accept that the Complainant has some rights in those marks for purposes of the first element.

The uncontested evidence before the Panel is that the Respondent hacked into the Complainant’s system and then managed to take control of the disputed Domain Names. Since that time, the Respondent has only sought to blackmail the Complaint into making a payment of “[USD]17,000 in Bitcoin” to obtain the return of the disputed Domain Names and presumably other illicitly obtained information. Such actions are tantamount to an attempt to sell a domain name to its legitimate owner and thus cannot be considered to reflect a right or legitimate interest. Further, it is not difficult for the Panel to conclude that the Respondent has acted in bad faith. Hacking into the account of another to acquire domain names based on that party’s claimed trademarks for purposes of reselling them at an exorbitant price back to their original owner is not only malicious but a pure bad faith act of cyber piracy. As such, the Complainant prevails on the third element as well.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Internally Represented

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Two-letter .com domain names like PV .com are extraordinarily valuable and sought after. They are the ultra-luxury real estate of the domain name space. Think, Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, the Peak in Hong Kong, and Belgravia in London. Just last week, the ultra-premium domain name, VT.com sold for USD $2.5 million. So when such a valuable domain name as PV .com is stolen, it is remarkable that the UDRP – a USD $1,500.00 procedure – is used to recover it.

The UDRP however, was not intended to be used to recover stolen domain names, but it nevertheless occasionally can and has been used successfully for this purpose. As Gerald Levine notes in his treatise, Domain Name Arbitration (at Page 476), “Although a fraudulent transfer raises potential contract or tort issues that are [technically] outside the scope of the Policy, the Panel may still decide to [order] the disputed domain name [transferred] if it finds that Complainant has established that all requirements of the Policy, aside from the fraudulent transfer issue, are met.”

In the present case, Panelist Georges Nahitchevansky meticulously evaluated all elements of the Complainant’s case against the three-part test of the UDRP and in particular, focused on the question of whether the Complainant had trademark rights. The “no legitimate interest” and “bad faith registration and use” parts of the test were easier for the Complainant to meet given that there was no response and there was an overt extortion attempt alleged. But when it came to trademark rights, the Complainant had difficulty in meeting the test given the nature of its trademark registrations and its limited evidence of common law rights. This often the case with stolen domain names as often stolen domain names have not yet been used as a trademark at the time that they were stolen, and in such circumstances the victims will have no recourse under the UDRP and must avail themselves of the courts. Moreover, absent bad faith use of a stolen domain name, such as extortion or infringement by the thief, the UDRP may not afford a remedy. As noted by attorney David Weslow (2017 ICA Lonnie Borck Memorial Award Recipient), in such instances courts may be the appropriate venue (Bloomberg BNA, 2015).

Ultimately in this case however, the Complainant was able to show some use of both PACKETVIDEO and PV including for emails and other purposes, and that its combined design and word registration at least conferred “some” trademark rights in PV, which was sufficient for the UDRP:

The absence of registered trademark rights in PACKETVIDEO, the limited extent of the evidence of common law trademark rights, combined with the questionable rights in “PV” that arose from a registration that included substantial design elements, led the Panelist to understandably struggle with this issue, noting that “there were significant questions regarding the strength of the Complainant’s claimed rights”. The weakness of the Complainant’s case for trademark rights corresponding to the Domain Name likely may have led to a different result if this case had not been an undefended stolen domain name case, but in the circumstances the Complainant provided just enough to get over the hurdle.

That being said, the UDRP is a blunt tool for dealing with stolen domain name cases. As explained above, the UDRP is not responsive to all domain name theft situations and nearly wasn’t in this case too. That is why a UDRP-style procedure to specifically address domain name cases as part of or ancillary to the ICANN Transfer Policy should be considered and I have suggested this as a member of the ICANN Transfer Policy Working Group. But even such a policy would still face difficulties particularly in cases where the Respondent responds and claims to have been a bona fide purchaser without notice of the theft, for value. An ICANN UDRP-style policy would be unable to handle such complex legal and factual questions. Nevertheless, thieves tend not to respond to cases of theft, and therefore there is likely a discrete type of such cases where a new policy specifically addressing theft could be helpful, especially considering that the alternative – going to court – is expensive and time consuming.

Domain Investor Shows How to Win a Fanciful Domain Name Case

AKAPOL S.A. v. Ehren Schaiberger, WIPO Case No. D2023-2284

<plasticol .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nick J. Gardner, Mr. Georges Nahitchevansky and Ms. Diane Cabell

Brief Facts: The Argentine Complainant, has since 1962, manufactured and sold a range of adhesives and associated products under a number of brand names. In 2022 and 2023, it acquired a portfolio of trademarks for the term “PLASTICOLA” and registered the domain name <plasticola .com> around May 2023. The Complainant’s predecessor had registered and used the domain name <plasticola .com .ar> since 2014. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 7, 2017, and resolves to a page hosted at DAN – a secondary marketplace – which indicates it is for sale for USD $6,995. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s acquisition of the disputed Domain Name was primarily for the purpose of selling it for valuable consideration in excess of the Respondent’s documented out-of-pocket costs directly related to the disputed Domain Name, which can be fairly assumed that it has been registered without any bona fide reason.

The Respondent contends he is in the business of buying and selling domain names and that over the course of more than eleven years, he has built a domain name portfolio of tens of thousands of domain names. The disputed Domain Name expired and “dropped” on February 7, 2017, and while scanning the daily expiry and drop lists, he identified it as a good descriptive keyword and brandable domain name to add to his stock-in-trade to offer to a new entrant. The Respondent goes into considerable detail as to what he describes as the “meticulous process” by which he selects domain names of interest to him, including a check at the USPTO database and the Respondent had no reason to search for “plasticola” because “plasticol” was the string that he would have been evaluating.

In the case of the Disputed Domain Name, he says that it had various positive attributes making it attractive to the Respondent as follows: It is just 9 characters long. It had an age of 13 years old. Older domain names tend to be more desirable because they have not been available for the public to buy. And they are more likely to have SEO metrics. It fitted an established naming convention as a type of “portmanteau” of keyword + the morpheme –ol: a suffix used in the names of chemical derivatives, representing “alcohol” (glycerol; naphthol; phenol), or sometimes “phenol” or less definitely assignable phenol derivatives (resorcinol). It is an “open vessel brandable” domain name that could be used for a variety of products or businesses. The Respondent says that there are many businesses around the world (unrelated to the Complainant) that have independently conceived of the term “plasticol” itself and are using it and provides a list of examples.

The Respondent also previously registered more similar domain names, including <citol .com>, <colol .com>, <electricol .com>, <focusol .com>, <foxol .com>, <friendsol .com>, <foodplastics .com>, <farmplastics .com>, <interplastics .com>, <nugol .com>, <plasticstrip .com>, <plastickingdom .com>, <prettyplastic .com>, and more. The Respondent also contends that the available evidence shows that the Complainant was only recently assigned limited trademark rights (class and geography) in the term “plasticola”. The original “Plasticola” was a relatively small and recent start-up that had no presence in either the U.S. or in the Republic of South Korea, where the Respondent has ties, at any time prior to the disputed Domain Name registration. Overall, the Respondent denies prior knowledge of the Complainant and adds that for the first time, he became aware of the Complainant was not until after the Complaint was filed.

Held: The Respondent has credibly denied that he had any knowledge of the Complainant or the PLASTICOLA trademark when the Respondent acquired the Disputed Domain Name. In accepting the Respondent’s denial of knowledge the Panel takes note that there is no evidence of any reputation in the term PLASTICOLA except possibly in Argentina, while the Complainant did not register <plasticola .com> until 2023. The Panel accordingly accepts that the Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name because of its value as a “portmanteau” term combining the dictionary word “plastic” with the common suffix “ol” and has never targeted the Complainant or its PLASTICOLA Mark. The Respondent’s motivation in registering or selling the disputed Domain Name was not to profit from or exploit the Complainant or its trademark. Accordingly, the Panel finds that the Complainant has failed to establish the second element of Paragraph 4(a) of the Policy.

The Respondent did not register or use the disputed Domain Name in bad faith either since the Respondent legitimately registered the disputed Domain Name for the above-stated reasons. Additionally, the fact that the Respondent offered the disputed Domain Name for sale or making use of Privacy service cannot in itself be deemed to indicate that the disputed Domain Name was registered, or is being used, in bad faith.

The term “plasticol” is used by a number of third parties and if the Respondent had been targeting the Respondent it would seem likely that he would have registered <plasticola .com> which would appear to have been available at the relevant time. He did not do so.

The Respondent is making a general offer of sale of a domain name consisting of a term which might be of interest to a variety of entities. This is not an activity that is condemned by the Policy unless it is accompanied by some indicia of bad faith and in the Panel’s view there is no such indicia to be found on the present record”. The fact that the Respondent offered the Disputed Domain Name for sale cannot in itself be deemed to indicate that the Disputed Domain Name was registered, or is being used, in bad faith.

Any searches the Respondent might have carried out at the time he registered the disputed Domain Name would likely have been in respect of the term “plasticol”. Absent actual knowledge of a third party using a variation of that term it cannot be the case that the Respondent ought to have searched for variations of the term formed by adding an additional letter to the term. Failure to carry out such a search is not “wilful blindness”.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Moeller IP, Argentina

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch:

In my view, this is one of the most important and interesting cases in recent memory. We all know that when it comes to “generic” domain names, a Complainant will have great difficulty in proving that it was the target of the registration. We have also seen that Complainants will run into the same difficulty when it comes to short domain names such as three-letter acronyms. But when it comes to more fanciful terms, Complainants tend to be more successful in demonstrating that they were the target of the registration. The reason of course, is that when it comes to more fanciful trademarks, it is easier to assume that it was not a coincidence that the Respondent selected the corresponding domain name and that the Complainant’s trademark was the target of the registration.

There is however a difficulty with this approach; “coincidences” are not always so farfetched. After all, if an African company thinks that a fanciful mark that is suggestive of its business would be attractive to its customers in Kenya, why would it be so farfetched for an American company to similarly think that the same fanciful mark would be attractive to its customers in Idaho? Moreover, it is even conceivable in some cases that the identical mark could be used by two respective companies in two respective jurisdictions for completely different goods and services.

These considerations bring to mind fundamental principles of trademark law. Trademark rights are of course jurisdictional and having rights in one jurisdiction will not generally preclude another party have equal rights in another jurisdiction. Also, absent sufficient fame or notoriety, trademark law allows two respective parties to both use the identical trademark even in the same jurisdiction, provided that their respective goods and services are sufficiently disparate. Given these basic precepts of trademark law, it is perfectly conceivable that a domain name investor can, in good faith, select a fanciful domain name that happens to be similar or identical to a pre-existing trademark. Indeed, the fact that someone else also thought that the mark was a particularly attractive and apt brand can lend credence to the claim that the domain name investor reached a similar conclusion and as a result, selected the corresponding domain name. In the trademark world, there is nothing wrong with two parties co-existing under an identical mark in different jurisdictions or for different services, so why shouldn’t the domain name investor invest in a domain name that may be of interest to a party wishing to enter the market on this basis? We mustn’t impose restrictions on domain name investors that are stronger than those imposed by trademark law itself.

Nevertheless, we also cannot let domain name investors surreptitiously target a fanciful brand owner and then claim that it’s a merely a coincidence. So, what’s the answer? We need to protect the fanciful brand owners and also to permit domain name investors, in good faith, to invest in fanciful domain names as permitted by trademark law.

The way to accomplish this is highlighted in this case. It is perfect example of the evidence that a domain name investor in a fanciful domain name corresponding to a pre-existing trademark can provide to substantiate that the investor registered the disputed domain name due to its inherent appeal and not to target the Complainant’s mark. Here, the Respondent dutifully laid out his criterion for selecting this particular domain name. This is key, as if credibly done it will show the Panel that there were genuine considerations and reasons that made this particular domain name attractive for registration apart from the Complainant’s mark. Registration of similar domain names, as the Respondent showed, also lends credibility to the Respondent’s claim. And the fact that there were third parties who also used the term lends credence to the notion that the Complainant is not singularly associated with the mark and as such is less likely to have been the target. The Panel here deserves substantial credit for hearing and assessing these considerations and reaching the right conclusion in this case.

Future Respondents should follow the model set out by the Respondent in this case and future Panelists should take not of the Panel’s fair-minded appreciation of the circumstances laid out by the Respondent.

Lastly, I must comment on one piece of killer evidence presented by the Respondent which probably played a prominent role in this case. The Respondent pointed out that if he really had been a cybersquatter, then he would have registered the exact match of the Complainant’s brand, i.e. Plasticola .COM – which was available for registration at the time that the Respondent registered Plasticol .com.

Complainant Failed to Establish Common Law Trademark

<thewarroom .ag>

Panelist: Mr. Calvin A. Hamilton

Brief Facts: The Complainant claims common law rights to THE WAR ROOM trademark and the design mark, in connection with the collaborative trading platform and its related products. The Complainant asserts that it has used each of the marks since at least as early as March of 2019. The Complainant provides information as Exhibits to its Complaint to demonstrate the use of THE WAR ROOM Marks and to support its claims to common law rights in the trademarks. In its Supplemental Reply Brief, the Complainant provides the Declaration of Ryan Fitzwater, Associate Publisher of the Complainant, as evidence of sales, promotional expenses, subscription, user metrics and earnings.

The Respondent contends that the Complainant has failed to submit any degree of persuasive evidence necessary to establish common law and reputational rights in the domain at issue and that the Complainant makes unsupported and unevidenced conclusory statements and provides third-party review blogs to base its secondary meaning assertion. The Respondent further contends that it registered the domain name in good faith and continues to use it in good faith and that the Complainant has failed to satisfy any of the requirements under the Policy which constitute evidence of the Respondent’s bad faith.

Held: The Complainant asserts that it holds common law rights in THE WAR ROOM Marks and does not currently hold a trademark registration. In reviewing and weighing the evidence submitted by the Complainant, the Panel is of the view that although at least some of the Complainant’s customers may associate THE WAR ROOM mark with the Complainant’s goods. However, the evidence is not altogether persuasive or conclusive on the issue of how the average customer for the Complainant’s product perceives the words of the subject mark in conjunction with the Complainant’s products.

Further, the WAR ROOM mark includes words of a generic and descriptive nature. Generic and descriptive marks require very strong evidence to establish secondary meaning. Additionally, a review of the internet space reveals that the War Room exists in a crowded field of similar marks. In this regard, the Panel is persuaded by the discussion between the Complainant and the USPTO introduced into evidence by the Respondent in its Reply, where the Complainant itself recognizes that “The War Room” exists “…in a crowded field of similar marks and is therefore entitled to a narrower scope of protection”.

Additionally, a search on the internet using the moniker the War Room provides links to several different sites, indicating that the Complainant does not exercise exclusive use of the mark in commerce. Further, it also demonstrates that the mark has not acquired the distinctiveness necessary to establish secondary meaning. The Panel, therefore, finds that the Complainant has not provided the evidence necessary to establish secondary meaning in The War Room and has failed to prove the association of those words with the Complainant. Therefore, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not established rights in the WAR ROOM mark under Policy ¶ 4(a)(i).

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Benjamin W. Janke, Louisiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Kyle Scudiere of SOLACE LAW, California, USA

Case Comment by Igor Motsnyi:

Igor is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal, motsnyi .com . His practice is focused on international trademark matters and domain names, including ccTLDs disputes and the UDRP.

Igor is a UDRP panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy.

The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

Complainant failed to establish common law trademark

While the UDRP applies to both registered and unregistered marks, proving unregistered mark rights for UDRP complainants is often mission impossible, in particular, when the alleged common law trademark consists of descriptive, generic or common terms used by different businesses and persons.

As Gerald Levine noted in his treatise: “unregistered marks stand on a different footing from those registered” (see “Domain Name Arbitration. Trademarks, Domain Names and Cybersquatting”, Second Edition, page 167).

In the <thewarroom. ag> case it seemed that Complainant tried and actually provided some relevant evidence and the Forum Panelist noted that “at least some of Complainant’s customers may associate THE WAR ROOM mark with Complainant’s goods”.

However, such proof, in the Panelist’s view, was insufficient as the Panelist pointed out that he is “reluctant to generalize from such a small sample to conclusions regarding the consuming public at-large” and found that “the evidence is not altogether persuasive or conclusive…”

What is also noteworthy in this case is that the Panel considered Complainant’s own submissions before the USPTO related to Complainant’s trademark application for “The War Room” that was later abandoned.

The USPTO submissions were introduced by Respondent as evidence in the UDRP proceeding. Complainant actually admitted in its USPTO submissions that “The War Room” exists “…in a crowded field of similar marks and is therefore entitled to a narrower scope of protection…”

Establishing unregistered trademark rights in respect of the terms that exist in “a crowded field” is always a challenge and even if complainant succeeds, it may still fail under the bad faith element if there is no evidence of targeting.

To establish common law trademark rights, complainants need to demonstrate the connection between their goods/services and the mark used in relation to such goods/ services as well as consumers’ association of the unregistered mark with the complainant’s goods/services.

In my opinion, the <thewarroom. ag> decision illustrates two points:

1) The importance of filing a response in UDRP disputes. I already wrote about the importance of response in UDRP proceedings in UDRP digest, vol 3.8.

In <thewarroom. ag> the Panel most likely would have reached the same conclusion even without a response. However, the response certainly helped Respondent, in particular since Respondent seemed to have provided convincing and plausible arguments (e.g. operation in a different business field) and evidence (e.g. Complainant’s submissions before the USPTO).

2) To establish common law TM rights in the marks “comprised solely of descriptive terms which are not inherently distinctive, there is a greater onus on the complainant to present evidence of acquired distinctiveness/secondary meaning”, WIPO Overview 3.0, section 1.3. The weaker the claimed mark is, the stronger evidence complainants must present to UDRP panels. While “The War Room” is not exactly a descriptive mark it consists of common terms and the phrase “the war room” is indeed widely used by various unrelated parties for different purposes. It is a crowded field and hence a greater onus for the Complainant.

One of the older cases that comes to mind is <tauber. com>, see here, where Complainant failed under the first element (and the two other elements) and the Panel noted that the word “Tauber” “appears to be a name used by a number of businesses unrelated to the Complainant”. As was successfully argued by Respondent in <tauber. com.: “Tauber” is a surname common in German-speaking countries, and that surname is widely used for various businesses and projects in the world. Numerous “Tauber” trademarks belong to and owned by different owners and applicants in different states, including the United States, Germany, Brazil and the Russian Federation, and are used throughout the world by different entities and individuals. Therefore, the word “Tauber” does not have a particularly strong connection with the Complainant”.

The Forum Panelist in the <thewarroom. ag> reached a similar conclusion in relation to the use of the terms “The War Room” by different persons: “a search on the internet using the moniker the War Room provides links to several different sites, including Stephen K. Bannon’s War Room; Bannon’s War Room; War Room Mobile on the Apple Store; War Room Infowars, etc. This indicates that the Complainant does not exercise exclusive use of the mark in commerce…”

The <thewarroom. ag> decision once again demonstrates how challenging it is to establish unregistered trademark rights for common / popular terms.

Complainants (their counsel) should either have strong evidence of unregistered TM rights and targeting or think twice before filing UDRP complainants in such cases.

Is Scoop Soldier Descriptive of Services?

Scoop Soldiers Service Company, LLC v. Carl Gregory, NAF Claim Number: FA2307002053790

<scoopsoldier .com>

Panelist: Mr. Alan L. Limbury (Chair), Mr. David S. Safran and Mr. Charles A. Kuechenmeister

Brief Facts: In 2019, the Complainant registered the service mark SCOOP SOLDIERS with USPTO, for pet waste removal services and the Complainant began using the domain name <scoopsoldiers .com>. The Complainant has conducted business under the SCOOP SOLDIERS mark in Arizona since 2020. Beginning in 2022, the Respondent began using the disputed Domain Name, which is the singular form of the Complainant’s mark and its Domain Name. The disputed Domain Name resolves to the website <poopydoo .com>.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not conduct business under the name Scoop Soldier and the disputed Domain Name is being used to confuse the public into believing that <poopydoo .com> is the same as the website for the Complainant at <scoopsoldiers .com>. The Respondent contends that PoopyDoo .com is a local small family business established in 2005, while the <scoopsoldier .com> domain name was a GoDaddy recommendation. The Respondent further contends that he didn’t even know it was going to the Complainant’s homepage as it was nothing more than an oversight.

Held: It is true that the Respondent is operating in the same industry as the Complainant but there is no evidence before the Panel to support the Complainant’s assertion that it has been doing business since 2020 under the SCOOP SOLDIERS mark in Arizona, which is separated by an entire state (New Mexico) and much of Texas itself from Complainant’s home base near Dallas, Texas. More importantly, both the Complainant’s mark and the domain name are descriptive in nature, describing the business in which both parties operate. This constitutes a plausible basis for the Respondent to have selected the domain name on its own merits, despite the domain name being registered 3 years after the Complainant’s trademark and domain name were registered and resolved to the Respondent’s “poopydoo .com” website. There is no impersonation, no pattern of bad faith conduct, and no evidence that the Complainant is famous, or even well-known in Arizona.

The Response strongly suggests that the Respondent was genuinely surprised by the Complaint and had no idea there was another Scoop Soldier out there. The Respondent’s assertion that the domain name was a GoDaddy recommendation does not amount to a denial of knowledge of the Complainant or its mark or domain name at the time of registration. However, the descriptive nature of the domain name and the difference between “soldiers” and “soldier” is consistent with an innocent intention even if the Respondent had been aware of the Complainant at the time of registration and when the domain name resolved to the Respondent’s website. Accordingly, the Panel considers there is no evidence upon which to find that the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name in bad faith to target the Complainant. Further, the descriptive nature of the Domain Name is such that the Respondent’s use of it to resolve to his <poopydoo .com> website has not been shown to be bad faith use.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Christopher R. Castro, Texas, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Nominative Fair Use

Law School Admission Council, Inc. v. Fischel Bensinger, NAF Claim Number: FA2307002054973

<lsatbyfisch .com>

Panelist: Mr. Nicholas J.T. Smith (Chair), Mr. Jeffrey J. Neuman and Mr. Michael A. Albert

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a not-for-profit organization that provides products and services that support candidates and schools through the law school admissions process, which includes the Law School Admission Test (LSAT). The Complainant asserts rights in the LSAT mark based upon use since 1948 and registration with the USPTO dated January 10, 1978. The disputed Domain Name reflects the name under which he promoted his business (LSAT BY FISCH) and has continuously used the Domain Name since 2008 for a website promoting his LSAT test preparation services. The Respondent’s services are recognized by local law schools in the New York area and the Respondent is known to the Complainant, having encouraged his students to purchase test materials from the Complainant and having engaged with the Complainant directly since 2008.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent does not use the Domain Names for any bona fide offering of goods or services or legitimate non-commercial or fair use as its sole apparent use is to pass off as affiliated with the Complainant for the promotion of unauthorized or counterfeit products. The Respondent contends that he has rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name as he is commonly known by the Domain Name and it makes a nominative fair use, as it describes the services he offers (LSAT test preparation services by Fisch[el Bensinger]). The Respondent further contends that the disputed Domain Name does not confuse consumers and the Complainant’s actions are a deliberate attempt to prevent the Respondent from teaching LSAT courses without paying it a licensing fee, a misuse of its market power.

Held: The Panel accepts the evidence that the Respondent, since 2008, has offered services preparing students for the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) under the name LSAT by Fisch, “Fisch” being an abbreviation of his first name and a nickname. The content of the Respondent’s Website supports the statements made in the Response that the Respondent operates a service independent of the Complainant, preparing students to study for the Complainant’s LSAT. While the Respondent’s Website does not contain an express disclaimer, however, there is nothing in the Respondent’s Website that would imply to a visitor otherwise. The doctrine of nominative fair use has been applied by UDRP panels, wherein the panels have concluded that applying the nominative fair use doctrine could also be appropriate in cases other than those involving a reseller of branded parts, provided that the respondent operated a business genuinely revolving around the trademark owner’s goods or services. Such services do not have to be authorized by a Complainant. The Oki Data standard has repeatedly been applied in the context of unauthorized resellers/repair companies.

The Panel is satisfied that the Respondent is making a bona fide offering of goods and services at the Domain Name. The Respondent is not seeking to pass off as the Complainant or as associated with the Complainant as there is nothing on the Respondent’s Website that suggests an affiliation with the Complainant beyond the fact that the Respondent offers services connected with the Complainant’s LSAT; indeed it would be difficult to identify how the Respondent could describe or advertise his LSAT test preparation services absent any use of the term “LSAT”. There is no evidence that the Respondent is seeking to take advantage of any similarity between the Domain Name and LSAT Mark beyond that which arises from a truthful use of the LSAT Mark to describe the services that the Respondent’s business provides. Therefore, the Complainant has failed to demonstrate that the Respondent lacks rights or a legitimate interest in the Domain Name.

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Wendy K. Marsh of Nyemaster Goode, P.C., Iowa, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Anderson J. Duff of DUFF LAW PLLC, New York, USA