How Would You Decide the Screencast .ai dispute?

In the dispute over the screencast .ai domain name, the legally represented Respondent claims that the term “screencast” has become genericized over the 15 years that have passed since it was first registered as a trademark. The Complainant asserts that it is still a valid trademark and that by offering screencast .ai for sale at a profit the Respondent is engaging in classic cybersquatting…

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 3.34), as we review these noteworthy recent decisions, with commentary from experts. (We invite guest commenters to contact us.)

‣ How Would You Decide the Screencast .ai Dispute?

(screencast .ai *with commentary)

‣ Guess Who Won This Case! A Teachable Moment About the Scope of the UDRP (takenote .ai *with commentary)

‣ Complainant Fails to Produce Proper Evidence (oziumus .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel: “Domain Name Hijacking Has Occurred” (meditechpharmaceutical .com)

‣ Meta Platforms Right in ‘META’ Trademark (metaquestfoundation .com *with commentary)

—–

This Digest was Prepared Using UDRP.Tools and Gerald Levine’s Treatise, Domain Name Arbitration.

Have Something to Say? Share your feedback with us or contact us to write a Guest Comment!

The ICA will attend the Domain Days Dubai meeting Nov 1-2, 2023. This is one-of-a-kind event in the MENA region’s domain industry. The conference brings together a diverse crowd of Domain Investors, Registrars, Registries, Monetization & Traffic, Web 3.0 Domains, Hosting & Cloud Providers, SaaS providers, and Industry Enthusiasts.

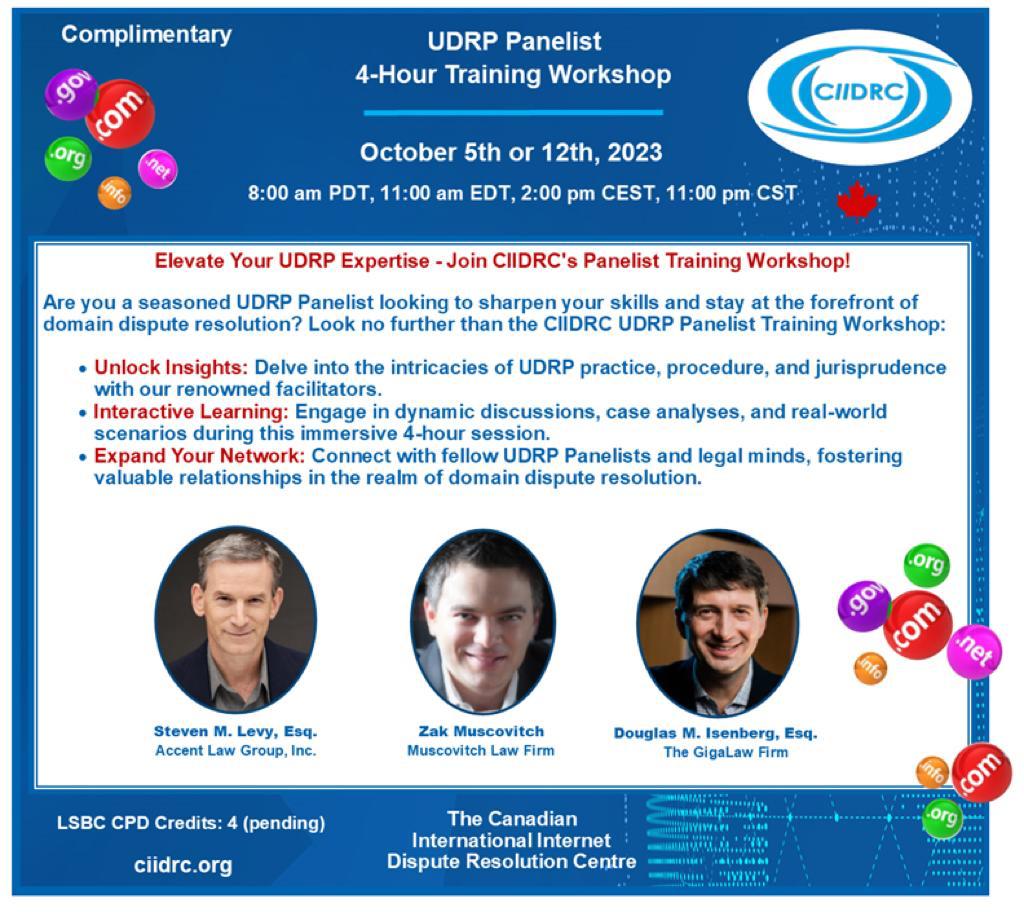

Kamila Sekiewicz, Zak Muscovitch, and Ankur Raheja will be representing the ICA. We’d love to meet with any members of our UDRP Digest community attending, so please get in touch if you have plans to be there.

How Would You Decide the Screencast .ai Dispute?

TechSmith Corporation v. Sergio Hernandez, NAF Claim Number: FA2306002050171

<screencast .ai>

Panelist: Ms. Luz Helena Villamil-Jimenez

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1987, is the owner of US trademarks Screencast .com® (registered on October 7, 2008) and Screencast® (registered on October 30, 2018). The Complainant registered the domain name <screencast .com> on June 20, 2002, and uses it for hosting online web facilities and applications for others for desktop and laptop computers and mobile devices, for video and screen capture and the creation of multimedia content. According to the Complainant, the trademarks are well-known globally with over 65 million users worldwide using Complainant’s products and services. The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 8, 2023, and is offered for sale for USD $5000. The Complainant alleges that USD $5,000 is a sum well in excess of registration costs, and this action is not a bona fide offering of goods or services or a legitimate non-commercial or fair use and given its worldwide reputation, it is likely that the Respondent was aware of Complainant’s rights at the time of the disputed Domain Name registration.

The Respondent contends that Panels have repeatedly held that “common words and descriptive terms are legitimately subject to registration as domain names on a ‘first come, first served’ basis.” Moreover, a merely descriptive or a generic trademark is allowed no protection under U.S. trademark law and a Google search for the term “screencast” results in links to numerous webpages that use the term “screencast” to generically refer to a service. In his Additional Submission, the Complainant further counters that the Respondent’s discussion on “genericness” in his Response is misplaced in this case, and that the Respondent has not provided any evidence of the Respondent’s common, descriptive, or generic use of the disputed Domain Name, unlike the authority cited by the Respondent.

Held: The Panelist does not accept at all the Respondent’s argument that the Complainant has no exclusive rights to the term “screencast” because it is a generic term. On the contrary, the Complainant’s marks are registered trademarks that are in full force and effect. The Panel accepts that in certain cases trademarks can lose their distinctive character and can become generic, but the genericness of a trademark registration does not occur automatically. In the present case, while the Complainant has demonstrated that its trademarks are widely used and have become known by consumers due to the type of services being offered, the Respondent seeks to justify its behavior by the alleged genericness of the trademarks on which the Complaint relies. As noted above, the disputed Domain Name is neither generic nor descriptive but instead consists of a registered trademark, and therefore the Respondent has no right or legitimate interest in the disputed Domain Name.

Further the fact that the disputed Domain Name, offered for sale, reproduces the registered trademark evidences a prima facie intention of the Respondent to cause confusion and attract internet users for commercial gain. The Panel cannot accept the Respondent’s defense based on that “ICANN precedent has established that neither mere registration, nor general offers to sell domain names which consist of generic, common, or descriptive terms can be considered acts of bad faith”. The premise supporting this assertion is not sustained since SCREENCAST .COM and SCREENCAST are registered, valid and duly protected marks, and therefore the registration of a domain name substantially identical to said marks for the purpose of selling it evidences that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith under Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: James R. Duby of DUBY LAW FIRM, Michigan, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Andrew Keyes of ROME LLP, California, USA

Case Comment by ICA Director, Nat Cohen:

Nat Cohen is an accomplished domain name investor, UDRP expert, proprietor of UDRP.tools and RDNH.com, and a long-time Director of the ICA.

How Would You Decide the Screencast .ai dispute?

In the dispute over the screencast .ai domain name, the legally represented Respondent claims that the term “screencast” has become genericized over the 15 years that have passed since it was first registered as a trademark. The Complainant asserts that it is still a valid trademark and that by offering screencast .ai for sale at a profit the Respondent is engaging in classic cybersquatting.

This is an interesting case that offers two very different views of how to apply the UDRP.

The Complainant provided evidence that supports a finding in favor of the Complainant on all three elements of the UDRP. Yet the Respondent claimed that it registered the domain name based on the current descriptive meaning of “screencast” and was not targeting the Complainant.

There is evidence supporting both sides. Which narrative, as Gerald Levine would say, is the more plausible?

The evidence to support that screencast has become genericized is pervasive. For instance, the Wikipedia article on “screencast” treats it as a descriptive term and makes no mention of the Complainant. Common Sense Media’s article on the best screencasting tools for the classroom reviews several tools for creating screencasts and makes no mention of the Complainant, see here.

I think the panelist here puts too much emphasis on whether the trademark is valid and whether the domain name matches the trademark. The panelist appears to give no credence to the Respondent’s evidence that “screencast” is now widely used in a descriptive sense which supports the Respondent’s claim that the registration was not made in bad faith to target the Complainant.

It seems that the Respondent’s attorney did not help their cause by trying to defeat the complaint on the first element by asserting that the trademark was no longer enforceable, which was a losing battle, and by asserting that the Respondent therefore had a legitimate interest in the mark, which was also a losing battle. Instead, it may have been a more persuasive to argue that registering a term that so many others were using descriptively did not adequately support a finding that the registration and use of the domain name was in bad faith.

The Panel made the inference that by registering and offering for sale a domain name that (aside from the .ai extension) is an exact match of the Complainant’s mark, the Respondent was targeting the Complainant in bad faith.

I would have found, instead, that there is sufficient evidence that “screencast” is now in such wide use as a descriptive term that on the balance of probabilities the more plausible inference is that the Respondent registered the domain name based on that descriptive meaning rather than to target the Complainant.

This is an example of the, at times, subjective nature of the UDRP and of how two panelists (assuming that there exists a panelist who would draw the same inference of good faith registration that I do), can look at the same evidence and draw opposing inferences.

Also of note is that paragraph 160 of WIPO’s Final Report on the UDRP from April 30, 1999, states in part:

Since the procedure would apply only to egregious examples of deliberate violation of well-established rights, the danger of innocent domain name applicants acting in good faith being exposed to the expenditure of human and financial resources through being required to participate in the procedure is removed.

The UDRP is not designed to adjudicate disputes where both parties can claim a legitimate right to the disputed domain name, as is the case here.

Guess Who Won This Case! A Teachable Moment About the Scope of the UDRP

Verbit, Inc. v. Registration Private / Domains By Proxy, LLC, NAF Claim Number: FA2307002053081

<takenote .ai>

Panelist: Mr. Jeffrey M. Samuels

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a technology company focused on AI-based transcription, speech recognition, and speech processing services, which acquired UK-based Take Note Ltd. in March 2022. Take Note is a UK Company and the owner of the UK Trademark for the mark TAKE NOTE (registered on August 15, 2008), which has been extensively promoted by Take Note, as well as by Verbit, to its target consumers through various forms of online media, including the Take Note website located at <takenote .co>. The Complainant points out that the UK Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name on March 19, 2023, shortly after the Complainant’s acquisition of Take Note and resolves to a single-page webpage purporting to offer “speech-to-text AI” transcription services and listing a London address. The Complainant alleges that it may be inferred, based on the notoriety of the TAKE NOTE mark and Respondent’s use of the disputed domain name, that Respondent had knowledge of Take Note’s and, by extension, Complainant’s rights in the TAKE NOTE mark at the time the disputed domain name was registered, and find bad faith under Policy.

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent’s use and registration of the disputed Domain Name as a means of diverting prospective customers demonstrates the Respondent’s bad faith activities. On the contrary, the Respondent contends that he is working on an AI voice transcription engine project, with a team of three people… the core AI transcription engine has been built and tested by two large companies (Sky TV and Equiniti), the main website has been built and a new beta website is in development with very high-quality graphics and animation and the project has been running for around a year and is scheduled to launch in the third quarter of 2023.

The Respondent further contends that the <takenote .co> website redirects to Verbit, which clearly states that it has been “rebranded.” The Response also indicates that the Complainant submitted no evidence that it owns the TAKE NOTE trademark, that Take Note has abandoned the mark and that the Take Note was not an AI company – they only do people-based manual translation. The Response further indicates that there are many other companies that use the Take Note name and that “take note” is an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary. The Respondent points out that he was invited by the Complainant to make an offer to sell the disputed Domain Name, that he was willing to accept USD $50,000 to sell the disputed Domain Name, and that he has not received a reply from the Complainant. Respondent also asserts that “[He] didn’t even know about Verbit buying a company called TakeNote in the UK.”

Held: The TAKE NOTE trademark is registered in the UK in the name of Take Note Ltd. and an Exhibit to the Complaint indicates that Take Note Ltd. is a subsidiary of the Complainant. Under such circumstances, the Panel concludes that the Complainant has rights in the TAKE NOTE mark. The Panel further notes, that the rebranding statement does not indicate that all use of the TAKE NOTE mark is to be discontinued, merely that the website has been rebranded. Noting that the abandonment issue results in a forfeiture of rights, the Panel determines that such issue is inappropriate for resolution under the expedited procedures of the UDRP and thus, declines to find that the TAKE NOTE mark has been abandoned.

The Panel finds that, prior to the commencement of the instant dispute, the Respondent has made demonstrable preparations to use the disputed Domain Name. However, whether such “use” may be considered the use of the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services is a more difficult issue. The Respondent indicates that he did not know of Verbit’s acquisition of Take Note but he obviously became aware of such fact at some point in time. And, while the Panel declines to find that the TAKE NOTE mark has been abandoned, Respondent’s not unreasonable belief that the mark was abandoned may be taken into consideration, as may be the fact that “take note” has a dictionary definition that relates, to some extent, to the products in issue. In view of the foregoing, the Panel is unable to conclude that the preponderance of evidence supports a finding that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name.

While it may be unclear whether the disputed Domain Name was registered in bad faith, based on the discussion above on the issue of rights or legitimate interests, the Panel concludes that the disputed Domain Name is not being used in bad faith. In reaching its decision in this matter, the Panel is mindful of the fact that the UDRP is designed for only a “small, special class of disputes. Except in cases of `abusive registrations’ made with bad-faith intent to profit commercially from others’ trademarks…, the adopted policy leaves the resolution of disputes to the courts….”

Complaint Denied

Complainants’ Counsel: Charles P. Guarino of Moser Taboada, New Jersey, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Well, I didn’t see this case ending up with a dismissal! When I began reading the facts, it initially seemed to me that the Complainant would prevail. Taking into consideration the UK trademark, the UK location of both parties, that both parties are in the transcription business, and lastly, the fact that “Take Note” though an attractive and apt for a transcription business, is still a somewhat creative name, it seemed just too much of a “mere coincidence” that the Respondent just happened to select the Disputed Domain Name.

Yet after reviewing the Panel’s thoughtful rationale for dismissal, it began making sense to me. Although not expressly noted in the decision, the nature of the Complainant and Respondent’s respective domain name adds some credibility to the contention that the Respondent was not aware and did not target the Complainant. The Complainant’s domain name is TakeNote.co and the Respondent’s is TakeNote.ai. If the Complainant had employed the .com, then the Respondent would have surely been aware of the Complainant since anyone who selects a domain name with an extension other than .com, tends to check out the .com domain name’s use. Here however, there was no reason that the Respondent would have checked out a “.co”, so it is therefore plausible that the Respondent was unaware of the Complainant when he selected his domain name. Of course, evidence of how prominent the Complainant was in Google searches at the time of the Respondent’s registration would have been interesting to see, since the Respondent would have likely conducted them prior to selecting his domain name.

Ultimately, what appears to have swayed the Panel that the instant dispute did not warrant transfer of the disputed domain name to Complainant under the UDRP, was that this was not an ‘entirely clear case’ such that transfer of the Respondent’s domain name – which it was using for what appears to be a nascent but genuine business. The Panel notes that the Complainant had rebranded to some extent and may have abandoned its trademark rights. Though not entirely clear nor unequivocal from the record as the Panel points out, this could be a factor which enables the Respondent to legitimately adopt and use the disputed Domain Name. In other words, should this matter head to court, it is possible that the Respondent would successfully demonstrate that the Complainant had fully rebranded and had fully abandoned its trademark rights. Secondly, “Take Note” is such a suggestive and apt name for a transcription service, that it is plausible (without evidence of notoriety of the Complainant at the time of registration) that the Respondent innocently registered the disputed domain name rather than targeted the Complainant. In other words, it is plausible that the Respondent has rights in the Domain Name and that it should be allowed to continue using it. Not “plausible” in the mere “shadow of a doubt” sense, but genuinely plausible in the sense that even if you prefer the strength of the facts in favour of the Complainant and have doubts about the Respondent’s bona fides, that you cannot say with sufficient certainty, that the Respondent is clearly a cybersquatter and should therefore have his domain name taken away. As the Panelist pointed out:

“The Panel is mindful of the fact that the UDRP is designed for only a “small, special class of disputes. Except in cases of `abusive registrations’ made with bad-faith intent to profit commercially from others’ trademarks…, the adopted policy leaves the resolution of disputes to the courts….” See Second Staff Report on Implementation Documents for the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy, Oct. 25, 1999, ¶4.1c. Based upon its review of the case file, the Panel is not convinced that the instant dispute warrants transfer of the disputed domain name to Complainant under the UDRP.”

This is a highly nuanced and correct approach for the Panelist to have taken. The Panelist may have shared misgivings about the Respondent’s position and may even have believed that if the matter heads to court, the Complainant would likely prevail. Yet such misgivings and even suspicions about which party is “likely in the right”, does not a clear case make. It would be an error and misapplication of the Policy to transfer a disputed Domain Name on the basis that the Complainant was 51% likely to be right, or even 85% likely to be right, when the Respondent has a plausible case that cannot be satisfactorily resolved by the UDRP, and therefore should not receive the ultimate and immediate sanction of the transfer of the Domain Name. After all, applying a mere ‘balance of probabilities’ test of the minimal 51% implicitly means that a Panelist acknowledges that there is a 49% chance that the Panelist got it wrong – which is a very troubling failure. Moreover, such ‘balances of probability’ are inconsistent with the overarching premise of the UDRP; that it is intended only for the clear cases, not the unclear cases. The UDRP orders transfers in 90%+ of cases, such that a dismissal in the small minority of unclear or edge cases which are beyond the scope of the UDRP, does not detract from its overall effectiveness. It is just these minority of cases where caution should be exercised in favuor of more just and sure resolution by the courts.

Here, the Panelist was cognizant of the limitations on his own fact-finding abilities given the limited record and the limited scope of the UDRP – and therefore was honest with himself and that this may not be a case of cybersquatting, but rather a trademark dispute – and therefore demonstrated exemplary self-restraint in deferring to the courts. Panelists should be recognized and applauded for precisely this type of self-restraint which is more admirable than feigning the ability and mandate to decide unclear cases in favour of the subjectively and uncertainly “more likely” right party.

Complainant Fails to Produce Proper Evidence

Niteo Products, LLC v. chenlong, NAF Claim Number: FA2307002054196

<oziumus .com>

Panelist: Mr. Steven M. Levy, Esq.

Brief Facts: The Complainant, founded in 1945, is a well-known manufacturer of air sanitizing and air deodorizing products sold under the coined trademark OZIUM. This mark is the subject of registrations at the USPTO (registered on June 12, 1990) as well as registrations in other countries around the world such as China, Canada, Australia, Mexico, and the European Union. The Complainant promotes its products through its website at <ozium .com> but products are only sold to end-use consumers through authorized retail channels such as Amazon, Walmart, and Target. The Complainant claims that its OZIUM trademarks have “acquired significant goodwill and public recognition” because it has “promoted them at considerable expense worldwide”.

The disputed Domain Name was registered on June 7, 2023, and the Complainant points out that it resolves to a website that diverts consumers impersonating the Complainant, uses copyrighted images of Complainant’s products, and claims to offer OZIUM products at heavily discounted prices. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent registered and uses the disputed Domain Name in bad faith where its activities infringe the OZIUM mark in violation of Policy ¶ 2, it disrupts Complainant’s business by claiming to offer competing products, and it seeks commercial gain by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant’s mark. The Respondent failed to submit a Response in this proceeding.

Held: The Complainant provides copies of two of its USPTO registration certificates, which name other entities, while the Complaint states that these registrations were “later acquired by the Complainant through a series of transactions”, however, it does not provide any supporting evidence. The Panel has, under its own discretion, reviewed these records and found that both USPTO registrations are currently owned by Niteo Products, LLC. Therefore, based on this evidence, the Panel finds that the Complainant has demonstrated rights in the mark under Policy. As for the remainder of the Complainant’s claimed trademark registrations, these are provided only in the form of a textual list mentioning such information as countries, marks, and registration numbers. Mere textual lists of trademark registrations do not constitute evidence of such registrations and so the Panel will not consider these here.

Impersonation, or passing oneself off as a complainant and diverting users to a respondent’s webpage, is neither a bona fide offering of goods or services nor is it a legitimate non-commercial or fair use under Policy. Here, the Complainant provides screenshots of the resolving website which prominently displays the OZIUM graphic logo and many photographs of the Complainant’s products. From this evidence, the Panel finds support for the claim that the Respondent is “directly infringing Complainant’s OZIUM Trademarks. Or, even worse, offers the sale of Complainant’s goods to scam consumers out of money, all while assuming the identity of Complainant.” Further, Policy ¶ 2 is a contractual obligation between the registrant and its registrar to which a complainant does not have privity and thus lacks grounds to assert a cause of action based thereon. As such, the Panel will not consider this line of argument.

The Complainant further claims that its OZIUM trademarks have “acquired significant goodwill and public recognition” because it has “promoted them at considerable expense worldwide”. The Complainant’s evidence consists of screenshots of its official website and those of some of its retail partners such as Amazon. While this evidence doesn’t directly speak to the Complainant’s claimed “considerable expense” or the reputation that the mark may have with consumers or the Complainant’s industry, the Panel is prepared to accept that the mark has gained some goodwill based on its sale through substantial and recognized retail channels. More convincing, however, is the use to which the Respondent has placed the disputed Domain Name to impersonate the Complainant and either operate a scam or sell what may be inauthentic goods.

Under the circumstances of Respondent’s use of the disputed Domain Name, the Panel finds that the Respondent has disrupted Complainant’s business and drawn users to its website for commercial gain based upon confusion with the OZIUM trademark. Thus, it has registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP, Indiana, USA

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

Case Comment by Panelist, Igor Motsnyi:

Igor is an IP consultant and partner at Motsnyi Legal, <motsnyi .com>. His practice is focused on international trademark matters and domain names, including ccTLDs disputes and UDRP. Igor is a UDRP panelist with the Czech Arbitration Court (CAC) and the ADNDRC, and is a URS examiner at MFSD, Milan, Italy.

The views expressed herein are Igor’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the ICA or its Editors. Igor is not affiliated with the ICA.

Lessons from winning a UDRP dispute or footnotes worth reading

This UDRP decision demonstrates that complainants should learn lessons not only from losing but also from winning UDRP disputes.

The Forum Panelist ordered the transfer of the domain name <oziumus. com> to Complainant but pointed out some flaws in Complainant’s submissions:

1. Complainant in <oziumus. com> failed to provide evidence of the assignment of the two US trademarks it relied on in the proceeding. The Panel noted in footnote 1 of the decision: “The submitted registration certificates name other entities… While the Complaint states that these registrations were “later acquired by Complainant through a series of transactions”, it does not provide any supporting evidence… However, the Panel has, under its own discretion, reviewed these records” and found that Complainant owned the two US trademarks.

2. For the remaining trademarks Complainant only provided textual lists of the registrations rather than certificates/extracts/screenshots of the registry. The Panel did not consider such registrations and noted in footnote 2: “Mere textual lists of trademark registrations do not constitute evidence of such registrations and so the Panel will not consider these here”.

Lack of evidence of Complainant’s trademark rights results in denial as demonstrated in <aviationtrader. com>, FA2304002042374, https://www.adrforum.com/DomainDecisions/2042374.htm (“the Complainant relies on two recent figurative trademarks, but these are both owned by “Sandhills Pacific Pty Ltd.,” not by Complainant. Presumably, this is the “Sandhills Pacific” which Complainant describes as its subsidiary, but Complainant has provided no proof of this relationship, let alone any evidence of authorization from the trademark owner to file this case. Nor has Complainant explained why the trademark owner was not named as a second complainant”).

Failure to furnish proper evidence of trademark rights may threaten an otherwise strong case for a UDRP complainant. In <oziumus. com> Complainant barely passed the first UDRP element and was close to failing it.

3. On the bad faith element Complainant claimed that its trademarks have “acquired significant goodwill and public recognition” because it has “promoted them at considerable expense worldwide” however it failed to provide evidence of “considerable expense”.

The Panelist also disagreed with Complainant’s reliance on par. 2 of the Policy (“Representations”) and noted that “The Panel finds Complainant’s reliance on Policy par. 2 inapplicable as “that line of reasoning has now been fundamentally disavowed…” In essence, Policy par. 2 is a contractual obligation between the registrant and its registrar to which a complainant does not have privity and thus lacks grounds to assert a cause of action based thereon. As such, the Panel will not consider this line of argument”.

Luckily for Complainant, this was not fatal to its case as other evidence available on the record indicated bad faith of the Respondent and targeting, in particular evidence that Respondent attempted “to impersonate Complainant by displaying a website that diverts and deceives customers” and used some images from Complainant’s own website.

Despite the above shortcomings in Complainant’s arguments and evidence <oziumus. com> appears to be an obvious case of targeting and cybersquatting.

However, in some cases, targeting is not so obvious. In such non-obvious cases complainants (their counsel) should try harder and failure to provide evidence confirming “considerable expenses” or proof that the mark is “widely-known” or “famous” results in denial, see e.g. CAC Case No. 104559 (<sampo. finance>): “The Panel first notes, that the Complainant did not provide any proof of the well-known status of its trademarks….A mere fact that the marks of the Complainant are registered in various jurisdictions does not automatically make them famous or well-known” and CAC Case No. 104070 (<SBERGAMES. COM>) “It might be the case that the Sber trademarks are in fact “well-known” or “famous” but the Complaint has the obligation to formulate such claim in a convincing manner and bring the evidence to support the allegation…”

I would encourage all complainants and their counsel to read each and every UDRP decision in cases they initiate, including the cases they win, with the purpose of understanding possible flaws in their submissions to avoid the same mistakes next time and to improve the quality of their next filings.

Panel: “Domain Name Hijacking Has Occurred”

Laura Grunwald v. Abhijeet Singh / Meditech Human Pharmaceutical, NAF Claim Number: FA2307002053262

<meditechpharmaceutical .com>

Panelist: Mr. Lars Karnøe (Chair), Mr. Alan L. Limbury and Mr. Saravanan Dhandapani

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a pharmaceutical company and claims rights in the MEDITECH mark through a common law trademark. The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has not used the disputed Domain Name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services as the Respondent uses the disputed Domain Name to sell goods that compete with those offered by the Complainant. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith and had actual knowledge of the Complainant’s rights to the MEDITECH mark prior to registering the disputed Domain Name.

The disputed Domain Name was registered by the Respondent on July 16, 2014, and he also holds trademark rights for the MEDITECH mark since May 10, 2015, in India. The Respondent contends that the Complainant has not provided substantiated proof of common law ownership of the trademark and further disputes the Complainant’s rights to the mark and its identity as well. Additionally, the Respondent alleges that the <meditechpharmaceutical .com> domain name became available because the Complainant had been suspended by the registrar for copyright claims in October 2013 brought by the Respondent and then the Complainant moved its business to <meditechpharmaceutical .net>.

Next, the Respondent contends that the revenue report which the Complainant provides to prove the volume of sales is an unsubstantiated Excel document and should not be considered evidence. Additionally, the Respondent contends that the proof Complainant provides to show keyword search volume is flawed since multiple companies are registered worldwide using the term “MEDITECH”. Lastly, the Complainant states in the Complaint, Point 24 that the Respondent was inactive until 2022, however, the Respondent argues that the Complainant acknowledged the Respondent’s existence and mark in 2015 when they posted the notice of a “counterfeit website”.

Held: The Complainant relies on its claimed use of the <meditechpharmaceutical .com> and <meditechpharmaceutical .net> domain names to establish common law rights in the MEDITECH mark yet none of the Whois information provided by the Complainant in relation to those domain names nor the material as to sales, advertising, website use etc. show the Complainant name Laura Grunwald. The Complainant’s own exhibit 15 shows Vithoon Jiravachborvornhij as “the lawful owner and user” of the <meditechpharmaceutical .net> domain name, in seeking to overturn the recent decision in ETABLISHMENTS TREMBLAY v. LAURA GRUNWALD, Claim Number: FA2303002036000. So, any trademark rights arising from the use of the MEDITECH mark on the website to which the <meditechpharmaceutical .net> domain name resolved prior to its recent cancellation cannot be attributed to the Complainant. Therefore, the Panel finds that the Complainant has not demonstrated common law rights in the MEDITECH mark.

RDNH: The Respondent contends that the Complainant is attempting to deprive the Respondent, the rightful, registered holder of the disputed Domain Name, of its rights to use the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant knew of the Respondent’s existence in 2015 when it had registered the MEDITECH mark as evidenced by its message dated November 25, 2015. The Panel finds that the Complainant knew that the evidence produced does not establish that the Complainant has any relevant trademark rights. The Panel finds there is sufficient evidence to support the averments of the Respondent and therefore finds that reverse domain name hijacking has occurred.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainants’ Counsel: Laura Grunwald, Germany

Respondents’ Counsel: Self-represented

Meta Platforms Right in ‘META’ Trademark

Meta Platforms, Inc., Meta Platforms Technologies, LLC v. Suresh Nair, WIPO Case No. D2023-2747

<metaquestfoundation .com>

Panelist: Mr. Jeffrey M. Samuels

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a United States social technology company that operates Facebook, Instagram, Meta Quest, and WhatsApp. Meta was formerly known as Facebook, Inc. and announced its change of name to Meta Platforms on October 28, 2021. The Complainant is a wholly owned subsidiary of Meta and is involved in the manufacture of virtual reality (VR) software and apparatus, which is now sold under the “Meta Quest” name. The Parent Company Meta is the owner of the US trademark for the mark META, (registered on August 28, 2018), and the mark QUEST, (registered on February 23, 2021). The disputed Domain Name was registered on February 20, 2022. The Complainant points out that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a parking page with PPC links and that “[t]here is no evidence of the Respondent having made any substantive use of the Domain Name” or “any evidence of its demonstrable preparations to use the Domain Name.”

The Complainant indicates that it has received much media attention in relation to the success of its VR products and the change of name of its products to “Meta Quest” and that this publicity regarding the name change took place prior to registration of the disputed Domain Name. The Complainant alleges that “[t]he Respondent could not credibly argue that it did not have knowledge of the META and QUEST trademarks when it registered the Domain Name.” The Complainant further maintains that the passive holding doctrine should be applied in this case because the META and QUEST marks are well known in connection with its VR software; that, despite its efforts to contact the Respondent, he has not come forth with any response or evidence of any bona fide intent in relation to the disputed Domain Name; and that Respondent, through its use of a privacy service, attempted to conceal its identity.

Held: The Panel determines that the Complainant has met its burden of proving that the Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed Domain Name. The evidence indicates that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a parking page with PPC links. As such, it cannot be found that the disputed Domain Name is being used in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services or for a legitimate noncommercial or fair use. Further, the disputed Domain Name was registered after it was publicly and widely announced that the Complainant’s VR product would be renamed to “Meta Quest”. The Panel finds that the use of the disputed Domain Name to resolve to a parking page displaying PPC links is a clear indication that the Respondent intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to its own website by creating a likelihood of confusion with Complainant’s trademarks as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation or endorsement of this website. Such circumstances are evidence of registration and use of the disputed Domain Name in bad faith within the meaning of the Policy.

Transfer

Complainants’ Counsel: Hogan Lovells (Paris) LLP, France

Respondents’ Counsel: No Response

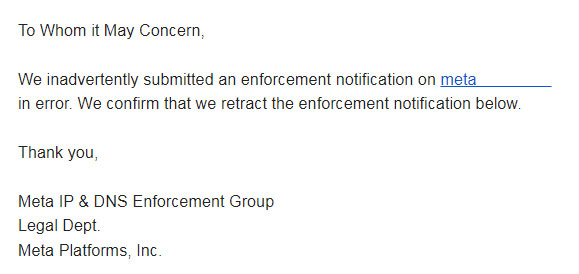

Case Comment by Newsletter Editor, Ankur Raheja: It is pertinent to note the date (October 28, 2021) on which the Complainant made public its intention to change its name to Meta Platforms (see related article). Domain Names registered prior to this date would not generally have been registered in bad faith. It is therefore commendable that this Complainant has at least in some cases, exercised caution and restraint in withdrawing “enforcement notices” where it has been advised that the chronology does not permit bad faith registration to have occurred. See below, a sample email from 2022, which was received by a domain registrant in such a case: