Panel: Complainant Cited “Nonexistent Cases” Resulting in “Suite of Massive and Misleading Errors”

It is well-established that a Respondent need not expressly make a request for RDNH in order for a Panel to consider the issue sui sponte. Indeed, as noted in UDRP Perspectives at 4.1, a Panel will not have satisfactorily discharged its duty under the UDRP without an express consideration of RDNH where the facts and circumstances warrant – regardless of whether it is requested by a Respondent. Rule 15(e) in fact provides that a Panel “shall declare” that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding, if after considering the submissions the Panel finds it warranted to do so. Implicitly, this means that not only is a request for RDNH not a precondition for a Panel considering RDNH, but the Rules actually command consideration of RDNH by a Panel, where appropriate. In the present case, the Panel noted that the Respondent did not make any express request for RDNH, but nonetheless considered RDNH and declared it, thereby fully discharging its obligation under Rule 15(e). Well done, Panel. Continue reading commentary here.

We hope you will enjoy this edition of the Digest (vol. 5.48) as we review these noteworthy recent decisions with expert commentary. (We invite guest commenters to contact us):

‣ Panel: Complainant Cited “Nonexistent Cases” Resulting in “Suite of Massive and Misleading Errors” (upscaleavenues .com *with commentary)

‣ Panel Uncovers Unbroken Chain of Title (highlevel .com *with commentary)

‣ SodaPdf .com v. PdfSoda .com – Confusing Similarity with Complainant’s Trademark (pdfsoda .com)

‣ Claimed Date of First Use in Trademark Registration Must be Proven Like Common Law Trademark Rights (eastmanmusic .com *with commentary)

‣ Use of Privacy or Proxy Service Not Itself an Indicator of Bad Faith (epiprotect .com *with commentary)

Panel: Complainant Cited “Nonexistent Cases” Resulting in “Suite of Massive and Misleading Errors”

Victor Adam Bosak III v. Robert Rogers, R D Rogers LLC, WIPO Case No. D2025-4174

<upscaleavenues .com>

Panelist: Mr. Robert A. Badgley

Brief Facts: Both parties are active in the real estate business in the Norfolk, Virginia area and have a history of prior dealings; following a falling‑out, part of their dispute now concerns the Domain Nam

The Complainant claims rights in the UPSCALE AVENUES trademark, which was previously registered with the USPTO and governed by a notarized May 2019 Trademark Co‑Ownership Agreement and Assignment with the Respondent. Under that agreement, the Complainant is recorded as having originated the “Upscale Avenues” brand in 2015, and the parties are described as equal undivided co‑owners of the trademark and related assets, including domain names and social media accounts. The agreement also provides that neither party may transfer or sell such assets without the other’s written consent, and notes that the Respondent had been using UPSCALE AVENUES in his real estate business since 2018. The Complainant alleges that, despite these terms, the Respondent took control of the trademark‑related assets and allowed the USPTO registration to lapse, which was ultimately cancelled on October 3, 2025. The Complainant then filed a new USPTO application on October 4, 2025, in an effort to continue and preserve use and ownership of the mark.

The Respondent registered the Domain Name on April 8, 2018, the same date he obtained a Virginia Certificate of Organization for Upscale Avenues, LLC, naming himself as registered agent. He later rebranded his business under the names Crescas Real Estate and Distinctly Real Estate and, at various times, redirected the Domain Name to his commercial websites. The Domain Name was later parked with real‑estate‑related links and more recently has resolved to a registrar landing page offering the Domain Name for sale at USD $7,500. The Respondent argues that this case centers on the Complainant’s assertion that his 50% interest in a now‑cancelled, jointly owned trademark registration entitles him to the Domain Name, even though the Respondent registered it in his own name as the founder, owner, and principal officer of Upscale Avenues LLC, the Complainant’s former employer. The Respondent maintains he has always been the sole registrant and owner of the Domain Name and has never transferred or assigned any interest in it to the Complainant.

Held: When the myriad and repetitive arguments raised in the Complaint and in several unsolicited filings thereafter are all considered, a few inescapable and essential facts remain. One, the Complainant registered the Domain Name on April 8, 2018, on the same day it had registered a Virginia limited liability corporation with the same name as the Domain Name. Two, the May 2019 Trademark Co-Ownership Agreement confirmed that the Respondent had registered the trademark UPSCALE AVENUES and had been using that mark in connection with his real estate business since 2018. Though the Complainant claims to have created that mark in 2015, the Complainant also acknowledges that the registration of Domain Name occurred during joint discussions about the UPSCALE AVENUES trademark. The Complainant’s May 2019 Trademark Co-Ownership Agreement suggests it waived objections to the Respondent’s use of the mark from 2018 and its March 19, 2019 registration.

Put another way, on the available record, the Panel cannot see how Respondent’s registration of the Domain Name during parties’ joint operation discussions involving the UPSCALE AVENUES trademark could have been done in bad faith. Because bad faith registration is not found here, the Complaint must fail. Whether the Parties may have other claims against each other under various legal theories that have been raised in this record is beyond the Panel’s remit and beyond the scope of the UDRP.

RDNH: The Respondent did not expressly request a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking. Nonetheless, the Panel here finds that the Complainant has abused the UDRP process and has committed RDNH. First, the Complainant should have known that its case was exceedingly shaky, given the Parties’ history and the May 2019 Trademark Co-Ownership Agreement, which expressly recognized that the Respondent had rights in the trademark that corresponds exactly to this Domain Name. Second, the Complainant’s serial submission of unsolicited filings to the Center, including at least five submitted before the Response was even filed, is improper and borders on abusive. The Complainant controls the timing of when a UDRP case is initiated, and hence has ample time to work up the facts and marshal the arguments that the Complainant believes will carry the day and secure the transfer of the domain name at issue.

Third, and remarkably, the Complainant cited several non-existent cases to the Panel in support of its case. The Complainant also cited several actual cases that do not stand for the proposition for which they were cited. If there was one errant citation or something that could be chalked up to momentary carelessness, the Panel might be disposed to overlook the error. But the sheer quantity of fake case citations compels something more than a shrug. In sum, in the circumstances of this case, the Panel finds that the Complainant’s failure to appreciate how weak its case was, the Complainant’s failure to abide by the rules of a UDRP proceeding by making new filings seemingly every time something new popped into Complainant’s head, and Complainant’s presentation of numerous false and misleading citations to non-existent UDRP cases, add up to an abuse of process worthy of a determination that the Complainant abused this process and committed Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied (RDNH)

Complainant’s Counsel: Self-represented

Respondent’s Counsel: John Berryhill, Ph.D., Esq., United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: It is well-established that a Respondent need not expressly make a request for RDNH in order for a Panel to consider the issue sui sponte. Indeed, as noted in UDRP Perspectives at 4.1, a Panel will not have satisfactorily discharged its duty under the UDRP without an express consideration of RDNH where the facts and circumstances warrant – regardless of whether it is requested by a Respondent. Rule 15(e) in fact provides that a Panel “shall declare” that the Complaint was brought in bad faith and constitutes an abuse of the administrative proceeding, if after considering the submissions the Panel finds it warranted to do so. Implicitly, this means that not only is a request for RDNH not a precondition for a Panel considering RDNH, but the Rules actually command consideration of RDNH by a Panel, where appropriate. In the present case, the Panel noted that the Respondent did not make any express request for RDNH, but nonetheless considered RDNH and declared it, thereby fully discharging its obligation under Rule 15(e). Well done, Panel.

The Panel also made an interesting and important general observation about the UDRP that sometimes escapes our specific attention. In refusing supplemental submissions by the Complainant, the Panel noted that “the Complainant controls the timing of when a UDRP case is initiated”. The fact that a Complainant “controls” the timing is an important consideration, not just on the issue of supplemental filings as it was here, but more generally as well. There is no statute of limitation applicable to UDRP Complainants and a Respondent will often find itself having to respond to a Complaint sometimes many years after the disputed Domain Name was registered – and within 20 days of the Commencement, subject to the extension of 4 days permitted under Rule 5(b). During this short window, a Respondent will often have to review the Complaint, consider its next step, consult with counsel, retain counsel, and pay for counsel. And counsel, once retained, will have to review the Complaint, investigate the Complaint which often includes looking for historical documents, conduct trademark searches, conduct factual research, interview the client, conduct case law research, and then draft a Response which is often 5,000 words long and attaches dozens of exhibits. It’s a very demanding process with some Responses taking up to 40 hours of work to prepare.

Under such circumstances, imagine the aggravation for a Respondent’s counsel when having undergone all of the foregoing steps in order to file a Response within the very short deadline permitted, is faced with supplemental complaints – each of which has to be reviewed and possibly responded to or not responded to. Responding to supplemental complaints takes time and money – often long after the Respondent has already been billed for the Response in the first place.

There is no absolute prohibition on filing any number of supplemental filings, per se. It is well established that additional submissions are not generally permitted whether designated “replies” or “rebuttals” and Paragraph 12 of the Rules provides for additional statements only at the Panel’s request in its sole discretion. Nevertheless, as a practical matter, there is nothing to prevent a Complainant from filing a supplemental pleading along with a request for consideration, thereby imposing on the Respondent – and the Panel for that matter – the obligation to review, consider, and respond to the additional pleading. It’s an unfortunate situation, as very often responding to such a supplemental will ultimately have been pointless if it is rejected by the Panel – but that’s a decision that the Respondent only learns of when the decision ultimately comes out.

Accordingly, some Respondent counsel have, as a result, taken the approach of not responding to most supplemental complaints unless the Panel confirms that it will accept the Complainant’s supplemental and then provides the Respondent an opportunity to respond. It’s not the best solution for a purportedly expedited procedure, as this additional back and forth can drag out the process and delay the decision by several weeks. Yet if the Respondent’s representative waits for a confirmation from the Panel that it will accept the Complainant’s supplemental submission before submitting its own supplemental filing, the Respondent’s representative risks a Panel proceeding to a decision without a response to the Complainant’s supplemental filing.

Fortunately most Panel decisions can be made without necessitating any response to a Complainant supplemental since the supplementals tend to be redundant or do not change the disposition of the case. This may enable a Panel to proceed even in the absence of a response to a Complainant’s supplemental.

The procedures for supplemental filings can easily be improved and standardized by requiring Complainants to request permission to file a supplemental before doing so and by briefly presenting the Panel with the reasons why, in their view, a supplemental filing is needed. The Panel can then decide to admit the supplemental or not. If the supplemental is admitted, the Respondent is then provided an opportunity to respond. This is procedural proposal #3 of the UDRP Exploratory Group that I participated in, found here – https://udrp.group/udrp-proposals/#procedural and the WIPO-ICA UDRP Review Report also recommends that a consistent approach be identified for procedures and parameters concerning supplemental filings.

By eliminating unsolicited supplemental filings, and only permitting, in effect, solicited supplemental filings, the procedures of the UDRP will be improved and an unfair burden that has been placed on respondents removed.

Lastly, this case stands out as a result of a most incredible circumstance. According to the decision, the Complaint included “fake” case citations. I will excerpt this part in whole because it is worth reading in whole:

“Third, and remarkably, Complainant cited several nonexistent cases to the Panel in support of its case. Complainant also cited several actual cases that do not stand for the proposition for which they were cited. If there was one errant citation or something that could be chalked up to momentary carelessness, the Panel might be disposed to overlook the error. But the sheer quantity of fake case citations compels something more than a shrug. The Panel is mindful of some recent instances where lawyers have been caught citing fake cases to courts of law in the United States, and in these instances it has been claimed that Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) programs were used by the lawyers, and the work product thereby obtained was rife with so-called AI hallucinations. Perhaps that is what happened here. Assuming so would be the most charitable interpretation the Panel could place on Complainant’s submissions to the Panel. Even if this were the explanation, the Panel would still condemn the decision to submit what Complainant submitted without doing some measure of verification that the cases cited were actually genuine and stood for the propositions advanced by Complainant in aid if its case. The failure to perform such due diligence (which, again, is the most innocuous construction the Panel can assign to these circumstances), and the resulting suite of massive and misleading errors in the materials submitted here for consideration, cannot be countenanced.”

Absolutely incredible. It was bound to happen eventually, and likely already has. Panels must be ever vigilant for spotting fake cases and misrepresenting case propositions, especially where a Respondent doesn’t respond because the Panel will be at the disadvantage for not having the benefit of the adversarial process to expose such malfeasance.

Panel Uncovers Unbroken Chain of Title

<highlevel .com>

Panelist: Mr. Phillip V. Marano (Presiding), Mr. Christopher K. Larus and Ms. Kimberley Chen Nobles

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a CRM software developer based in Dallas, Texas and has online presence at <gohighlevel .com> website. The Complainant owns a valid and subsisting registration for the HIGHLEVEL trademark before the USPTO (registered: April 8, 2025; first use: July 3, 2018). The California-based Respondents include Weedmaps, a technology company that provides cannabis-related product information and delivery services, and Ghost Management Group, LLC, a cannabis-focused venture capital firm. Both are based in Irvine, California. At the time of filing the Complaint, the disputed Domain Name was resolved to a GoDaddy parking page. The Parties dispute the specific date on which the Respondent came to own the disputed Domain Name. According to the Respondent, the “Complainant incorrectly asserts that Respondent did not acquire the domain name until 2024”, whereas the “Respondent acquired the disputed Domain Name on July 18, 2012.”

The Complainant alleges that the Respondent has registered and used the disputed Domain Name in bad faith as the Respondent is passively holding the disputed Domain Name and that the Respondent has no “credible explanation for the choice of the domain name or lack of interest in selling it for [USD] 200,000.” The Respondent contends that “’high level’ is a commonly used and dictionary-defined phrase” and it “believed that the domain name would be a good fit for its business” in a manner consistent with its dictionary or descriptive meaning. Furthermore, the “Respondent’s lack of interest in selling the domain name clearly evidenced that the Respondent did not purchase the domain name for the purpose of selling it, even for a large amount of money.” In response to the procedural order, the Respondent provides evidence that by at least July 18, 2012, over five years before the Complainant was formed Mr. Hartfield (co-founder of Weedmaps, LLC) owned the Domain Name.

Held: It is undisputed that the earliest date on which the Complainant acquired rights in its HIGHLEVEL trademark was July 3, 2018. It is also undisputed that an individual named Mr. Hartfield acquired the disputed Domain Name on July 18, 2012. The Panel concludes that the evidence on record is sufficient to consider the original July 18, 2012, transfer date of the disputed Domain Name to Mr. Hartfield as the date on which the Respondent came to own the disputed Domain Name. And, moreover, the Panel concludes that the Respondent has established an unbroken chain of possession of the disputed Domain Name, and that the transfer date from Mr. Hartfield to Ghost Management Group, LLC “sometime between 2012 and 2023” is not a ruse to hide a material change.

Therefore, the Panel finds that the Respondent did not register the disputed Domain Name in bad faith. In the opinion of the Panel, and contrary to the Complainant’s arguments, it is immaterial in the particular circumstances of this case to the assessment of bad faith that Mr. Hartfield used a personal registrar account to acquire the disputed Domain Name on July 18, 2012. There is no evidence that the change from a personal to a corporate holding was done to either in an attempt to distance the Respondent from the bad faith acts of Mr. Hartfield, to mask a true change in the underlying control, or to obfuscate any attempt by the Respondent to take advantage of the Complainant’s rights.

RDNH: Based on the evidence on record, the Panel finds that the Complaint has not been brought in bad faith and does not constitute an attempt at Reverse Domain Name Hijacking. Rather, the Panel acknowledges many of the evidentiary inconsistencies observed by the Complainant and recognizes that the Complainant would have no way to know about the Respondent’s initial registration date or the steps the Respondent made towards bona fide legitimate commercial use, without an affirmative reply from the Respondent to a cease-and-desist letter or the Complainant’s purchase offer.

That is why the Panel issued its Procedural Order. And even upon review of all evidence submitted by both parties in reply to that Procedural Order, the Panel further acknowledges that some evidentiary inconsistencies remain unresolved.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: Represented Internally

Respondent’s Counsel: Friedland Cianfrani LLP, United States

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: It should be noted that even the most rudimentary or wrong-headed and futile Complaints often require a considerable amount of work to respond to. All that a Complaint is required to contain are essentially a recital of the three UDRP elements and otherwise be administratively compliant with the Rules. Once commenced, a Respondent will have to respond to the Complaint irrespective of its merits and this usually requires a comprehensive Response that covers every single allegation made by a Complainant. Years of experience show that it is also wise to anticipate and to address allegations that are not in the Complaint but that the Panel may nevertheless conceive of on its own initiative despite not being raised in the Complaint.

An allegation that a domain name was registered and used in bad faith takes just but a line of text. Yet the refutation of the allegation may very well entail extensive historical investigation, production of corporate records, registration receipts, transfer documentation, historical screenshots, affidavit evidence, and much more. Ultimately however, that is how it has to be as there is no practical means of disposing of a case, however meritless, without responding, often vigorously and comprehensively.

Of course, Panels as well must often contend with having to dissect, navigate, and comprehend, often complex, convoluted, unclear, and incomplete facts in order to finally resolve a case, and moreover must do so in a manner which satisfactorily relays the material factual and legal aspects of each case in a written decision. Here, the Panel did an especially admirable job of wading through a factually complex history of domain name registration in order to arrive at the correct conclusion, namely that the Respondent had established an unbroken chain of possession of the disputed Domain Name. Indeed, I recommend bookmarking this case for its excellent discussion and analysis of the issue of ‘chain of title’.

As noted in UDRP Perspectives at 0.16, determining the date of a disputed Domain Name’s registration is often crucial where there is a question of whether the domain name registration or trademark rights came first. Nevertheless, the date of registration is often unknowable by a Complainant prior to bringing a Complaint because Whois privacy has caused the deterioration of historical Whois records, which could often previously be used to determine when a domain name changed hands.

In the present case, the Panel based in part its decision to decline to find RDNH based upon its conclusion that “the Complainant would have no way to know about the Respondent’s initial registration date or the steps the Respondent made towards bona fide legitimate commercial use, without an affirmative reply from the Respondent to a cease and-desist letter or the Complainant’s purchase offer”. Although a Respondent has no obligation to respond to a cease-and-desist letter or to a purchase offer, the failure to clear up a Complainant’s misapprehensions with regard to a registration date and entitlement to a Domain Name can come into play when considering RDNH, as it did here.

Nevertheless, as also noted in UDRP Perspectives at 0.16 although registration dates may not be easily or conclusively determined by Complainants, Complainants must still make the effort to investigate registration dates. Complainants can do this by compiling circumstantial evidence of when a domain name was registered by the Respondent. Such circumstantial evidence can include for example, evidence of the change of use of a domain name based upon historical web archives or a change of registrar. There are also Whois databases available on a subscription basis that provide historical Whois histories, which are particularly helpful for older Whois records before use of privacy services and GDPR became prevalent. Some commentators have suggested that any professional representative filing complaints has an obligation to subscribe to such services to do the necessary research and have access to the necessary evidence before initiating a Complaint. In any case, such evidence, if sufficient, can sometimes be used to draw a reasonable and supported inference of the registration date or at least try to narrow down the date range. Where Complainants do not make this effort however, they should not be permitted to avoid RDNH based upon their own failure to take reasonable steps to investigate their own claims prior to launching willy nilly, a UDRP proceeding and thereby put a Respondent and a Panel to substantial effort and expense.

In the present case, it is not entirely clear whether the Complainant made such effort. But even assuming that it made a reasonable effort and was stymied by lack of access to the historical series of events which resulted in an unbroken chain of title residing with the current Respondent, I still find the Complainant’s own allegations troubling. According to the decision, “the Respondent’s inactive or passive holding of the disputed Domain Name “originally displaying a message from the years 2000 through 2001 that state a corporate website would be live with ‘a couple weeks’, then [as of May 30, 2025] eventually resolving to a landing page having only a banner advertising that the domain name is for sale” was inter alia, evidence of the Respondent’s lack of rights. Yet by the Complainant’s own admission, the earliest use of its trademark was 2018. So the Complainant expressly relied on “non-use” for a website during a period that was 18 years prior to its trademark rights. This implicitly seems to suggest that the Complainant was fundamentally misguided in its approach to the UDRP if it was relying on the Respondent’s conduct from before it acquired trademark rights, and also points to it seemingly being aware that the Domain Name registration preceded its own trademark rights.

Furthermore, when it came to the issue of bad faith, the Complainant argued that “the Respondent’s unresponsiveness to the Complainant’s offer to buy the disputed Domain Name even for the high price of [USD] 200,000 demonstrates that the Respondent is holding out for an even larger offer from Complainant”. The fact that the Complainant made a $200,000 offer strongly suggests that the Complainant itself didn’t believe that it had an entitlement to the Domain Name. If the Complainant genuinely believed that the Respondent had no legal entitlement to the Disputed Domain Name, then $200,000 is an extraordinarily high price to offer for a domain name that is essentially worthless to all but the Complainant. This strongly suggests that the Complaint was nothing other than an abusive filing in which the Complainant used the UDRP as a “Plan B” i.e. using the Policy as an alternative means of acquiring a desirable domain name after failing to acquire the domain name in the marketplace (See for example, TOBAM v. M. Thestrup / Best Identity, WIPO Case No. D2016-1990 (Adam Taylor, Panelist)).

Yes, as the Panel ultimately uncovered inter alia through its Procedural Order, there were a series of transactions which together demonstrated a pre-existing right and unbroken chain of title which could not have been known by the Complainant when it filed its Complaint, but it remains unclear on what reasonable basis the Complainant alleged that its rights pre-existed the Respondent’s and further appears at least, that the Complaint only brought the UDRP after failing to buy it, thereby implicitly acknowledging its lack of entitlement.

SodaPdf .com v. PdfSoda .com – Confusing Similarity with Complainant’s Trademark

7104189 Canada Inc. (D.B.A. Gestion Avanquest Canada) v. Ngo Minh Tuan, WIPO Case No. D2025-4112

<pdfsoda .com>

Panelist: Mr. Flip Jan Claude Petillion

Brief Facts: The Complainant is a software publisher creating and developing software products. The Complainant offers an all-in-one PDF solution under the brand SODA PDF. The Complainant is the owner of various wordsmarks for SODA, including the EU trademark (November 30, 2010); and Canadian mark (May 14, 2013). The Complainant operates via the domain name <sodapdf .com>, registered in October 2009. The disputed Domain Name was registered on October 11, 2019, and resolves to a website which appears to offer free PDF and other converting tools under the name “PDFSoda”. The Complainant alleges that the similarity between the Complainant’s SODA mark and the Respondent’s offerings on the disputed Domain Name suggests a lack of independence in the Respondent’s business activities.

The Complainant further adds that instead of engaging in a distinct and original business venture, the Respondent’s actions appear as an ill-concealed passing-off attempt to leverage the reputation and recognition built by the Complainant over years of extensive operation. The Respondent contends that the disputed Domain Name consists of two common, descriptive English terms and that, while the Complainant holds trademark registrations for the word “soda” in relation to software and SaaS services, this does not confer an exclusive monopoly over the ordinary English word “soda” in all contexts or combinations. The Respondent further contends that the word order is reversed, the branding and logo design are entirely different, and the Respondent’s website includes a visible disclaimer on every page.

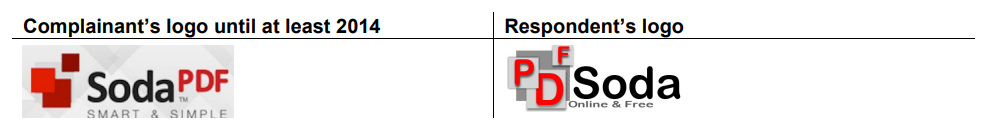

Held: In the Panel’s view, the combination of incorporating the Complainant’s distinctive SODA mark with the term “pdf” increases the risk for confusion with the Complainant and its business. Indeed, the Complainant’s evidence shows it offers PDF software tools under its SODA mark, and often uses the combination “SODA PDF”, e.g., through the domain name linked to its official website. Therefore, the Panel finds that the disputed Domain Name in itself carries a risk of implied affiliation with the Complainant and its SODA mark. The Panel further observes that the disputed Domain Name resolves to a website offering free PDF tools similar to those of the Complainant, and that the presence of a disclaimer on the Respondent’s website cannot play in its favour, as it appears the disclaimer was added after the filing of the complaint. Finally, the Panel observes that the Respondent’s logo presents remarkable similarities with the logo used by the Complainant until at least 2014:

In the circumstances of this case and on the balance of probabilities, the Panel does not consider the use of the disputed Domain Name to be bona fide, legitimate or fair.

The Panel further finds it very unlikely that the Respondent was unaware of the Complainant and its trademark rights when it registered the disputed Domain Name a the disputed Domain Name incorporates the Complainant’s distinctive trademark in its entirety, and combines it with a term which can easily be linked to the Complainant’s business. Also the Respondent’s logo presents remarkable similarities with the logo used by the Complainant until at least 2014. The Respondent uses the disputed Domain Name to offer tools at least similar to the Complainant’s software tools, albeit for free. In the Panel’s view, the above circumstances indicate that the Respondent has intentionally attempted to attract Internet users to its website for commercial gain or other such purposes inheriting to the Respondent’s benefit, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the Complainant and its trademark.

Transfer

Complainant’s Counsel: Benoît & Côté Inc., Canada

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Claimed Date of First Use in Trademark Registration Must be Proven Like Common Law Trademark Rights

Eastman Music Company v. bradley Schmidt, WIPO Case No. D2025-3808

<eastmanmusic .com>

Panelist: Mr. W. Scott Blackmer

Brief Facts: The Complainant, headquartered in California (US), designs, manufactures, and sells musical instruments. The Complaint does not describe its sales channels other than the Complainant’s website at <eastmanmusiccompany .com>, which is linked to social media sites. The Complainant holds US trademark registrations for EASTMAN dated March 9, 2010 and September 13, 2016, both claiming first use in commerce on January 1, 1992. The Panel notes that the first trademark was originally registered to Eastman Strings, Inc., a Maryland, United States corporation, and later assigned to the Complainant. The disputed Domain Name was created on May 5, 2004, and is registered to the Respondent Bradley Schmidt, who identifies himself as a music teacher in Minnesota. The Respondent states that he purchased the disputed Domain Name on May 5, 2004, under an agreement with the Eastman Music Store in Faribault, Minnesota. The Respondent says he had been teaching private music lessons at the store since 1987. It appears that the Respondent never developed such a website.

The Complainant argues that if the Respondent had any legitimate connection with Eastman Music, Inc. of Minnesota, that interest was extinguished when that company went out of business and the Respondent offered the disputed Domain Name for sale. The 2021 email in which the Respondent identified the Complainant as “the best fit” buyer for the disputed Domain Name suggests that the Respondent’s ‘primary intent was to profit from or otherwise exploit the Complainant’s EASTMAN marks in excess of out-of-pocket costs.” The Respondent contends that the Complainant’s registered EASTMAN trademark post-dates the long-established Eastman Music business in Faribault, Minnesota with which the Respondent was affiliated, and he denies any intent to attack the Complainant’s mark. The Respondent further argues that he acquired the disputed Domain Name in 2004 with reference solely to the existing business in Minnesota, while the Complainant at that time had only recently started operating and cannot credibly claim to have established a reputation as “Eastman Music” dating back to the 1990s.

Held: Contrary to the implications in the Complaint of longstanding use of the EASTMAN mark associated with the Complainant, the evidence indicates that in May 2004 the Complainant was relatively newly formed and just beginning to establish an online presence. It would not quickly acquire distinctiveness for trademark purposes with the name “Eastman”. “Eastman” is an English family name and produces numerous leading Internet search results unrelated to the Complainant. The Respondent, on the other hand, was a music teacher connected with the much longer established Eastman Music, Inc., which operated a local music store in Faribault, Minnesota and to all appearances did not compete online with the Complainant in California or Eastman Strings in Maryland.

The Respondent plausibly denies awareness of the Complainant until the Complainant’s webmaster contacted the Respondent in 2005 about bartering for a transfer of the disputed Domain Name. Given those facts, the Panel considers it more likely that the Complainant did not have common law trademark rights yet by May 2004 (WIPO Overview 3.0, section 3.8.1) and even if it did, the Respondent was unaware of them and selected the disputed Domain Name with reference to Eastman Music of Minnesota, not the Complainant The Respondent’s subsequent conduct, such as negotiating for a higher sales price for the disputed Domain Name two decades later, does not change the facts around the registration of the disputed Domain Name.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: Renner, Otto, Boisselle, & Sklar, LLP, United States

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: Among other notable aspects, this case reminds us that the claimed date of first use in a trademark registration means nothing without evidentiary support. As noted by the Panel to its credit, “the Complainant cites its trademark applications claiming first use in commerce in 1992, but the Complaint does not establish a record to support acquired distinctiveness of EASTMAN as a common law mark before trademark registration in 2010”. Any trademark right prior to a trademark registration date is essentially a claim of common law or unregistered trademark rights for the purpose of the UDRP, and accordingly as the Panel noted in reference to the WIPO Overview at section 1.3, “would typically require, for example, historical evidence of sales and marketing, as well as industry, consumer, and media recognition associating the mark with the Complainant”. The Panel also provides us with an important distinction that those less familiar with the UDRP may not readily appreciate. The Panel stated that “given the trademark registrations, it is not necessary [for the Complainant] to rely on a common law mark to support the first element of the Complaint, but the lack of evidence on this point is significant for the third element”. Exactly, and well noted.

And when it came to the third element, the Panel found the Complaint lacking because notwithstanding that it had registered trademark rights as of 2010, it still needed to show that “it had trademark rights in May 2004 when the Respondent registered the disputed Domain Name”, i.e. prove common law trademark rights from prior to May of 2004, and also of course, that “the Respondent more likely than not was aware of the Complainant’s mark in May 2004 and meant to exploit it”. Note the distinction here between three separate elements here; firstly the Complainant must prove trademark rights which existed prior to the Domain Name registration, and then must prove awareness of the trademark, which generally involves evidence of reputation, and then finally it must prove not just awareness, but also intent to exploit it, i.e. to target the trademark.

In the present case, the Panel found not only that prior to the Domain Name registration the Complainant “was relatively newly formed and just beginning to establish an online presence”, but that the Respondent had a credible explanation that he registered the Domain Name for a reason that had nothing to do with the Complainant, i.e. a local Eastman Music store. Well done, Panel. A particularly well-written decision which employed excellent analysis in reaching the right conclusion.

Lastly, the decision is noteworthy for a footnote included in the decision which states:

“The Panel notes as well that the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name using a domain privacy service, which the Complainant emphasizes, is not convincing evidence of bad faith. There are many legitimate reasons for doing so, such as avoiding spam and identity theft, and it is notable that the Respondent has not taken steps to evade communications with the Complainant or the Center.”

Well said. All too often a Complainant will throw in the argument that the Respondent’s “use” of a privacy registration is evidence of bad faith. Not only are there many legitimate uses for a privacy service as the Panel points out, but at most registrars private registrations are implemented on all domain names by default without any affirmative steps or decision taken by a Respondent, and as such are completely meaningless in and of themselves for the purpose of determining bad faith under the Policy. This has been so since at least 2018 when GDPR came into force and by now Complainants should know better than to make such spurious arguments and Panels should have little patience for them.

Use of Privacy or Proxy Service Not Itself an Indicator of Bad Faith

Abena Holding A/S v. shaun miglore, ION Management, WIPO Case No. D2025-3985

<epiprotect .com>

Panelist: Mr. Steven A. Maier

Brief Facts: The Complainant, registered in Denmark, is the owner of various trademark registrations for the mark EPIPROTECT, including Sweden trademark (November 1, 2013); Denmark trademark (March 29, 2025); and International trademark (May 25, 2025). The disputed Domain Name was registered on September 22, 2016 and is passively held. The Complainant argues that, under WIPO Overview 3.0 ¶3.3, four factors apply to passive holding and that all factors are satisfied in this case, including use of proxy by the Respondent to conceal his identity. The Complainant further alleges that the Respondent can have had no legitimate reason for registering the disputed Domain Name, and can have done so only for the purpose of selling it to the corresponding trademark owner.

The Respondent contends that he is a doctor practicing in the United States, and that he has been involved in over 30 business ventures. He registered the disputed Domain Name in 2016 for use in connection with a proposed epinephrine delivery and safety product, and that he also registered the domain names <epiright .info> and <epi911 .com> at the same time. The Respondent further contends that the term “epi” is a common shorthand for epinephrine, which appears in hundreds of domain names and trademarks in the medical field, and that the word “protect” is a descriptive term. The Respondent further adds that he heard nothing from the Complainant for nine years after registering the disputed Domain Name, and seeks a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking against the Complainant.

Held: The Panel finds there to be no basis to find, or to infer, that the Respondent was aware of the Complainant’s trademark when he registered the disputed Domain Name. At that time, in 2016, the Complainant owned only its Sweden trademark registration and, as the Panel has observed above, it has provided no information whatsoever concerning its use in commerce of that trademark. It is well-established in prior cases under the UDRP that a respondent is not deemed to have “constructive notice” of a trademark registration alone (see paragraph 3.2.1 of WIPO Overview 3.0). In these circumstances, it is incumbent on a complainant to come forward with evidence of the history, use and public profile of its trademark, in order to demonstrate that the respondent was likely to have been aware of its trademark.

Further, based on the Panel’s limited review of the Complainant’s <epiprotect .se> website, the Complainant says EPIPROTECT launched in 2024. While the website also refers to scientific studies that pre-date that launch, the earliest of these that refers to the mark EPIPROTECT appears to be dated 2018. With regard to the Respondent’s submissions, the Panel finds it credible that the Respondent could have registered the disputed Domain Name, in conjunction with two other “epi”-related domain names, in connection with a proposed epinephrine delivery product. While the Complainant claims the EPIPROTECT mark to be distinctive, owing to it being an invented term, the Panel observes nevertheless that the term “epi” is in common use in the medical field and that its combination with the dictionary term “protect” does not result in a mark capable of referring only to the Complainant’s product.

Finally, the four factors the Complainant correctly identified as relevant to bad faith in a passive domain registration: (1) The Panel does not find the Complainant’s EPIPROTECT mark to be notably distinctive. Nor has the Complainant tendered any evidence of the reputation of that mark; (2) The Respondent submitted a Response within the time specified by the Rules; (3) Use of a privacy/proxy service alone is not evidence of bad faith. Further, there is no evidence that the Respondent provided false contact details to the Registrar, and the Registrar promptly disclosed those details in connection with the proceeding; (4) The Panel does not consider it to be implausible that the disputed Domain Name could be put to good faith use. In the circumstances, the Complainant has failed to meet its burden of establishing that the disputed Domain Name was registered and is being used in bad faith.

RDNH: The Respondent requests a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking based, at least in part, on the premise that the disputed Domain Name was registered some nine years prior to the Complainant’s earliest trademark registration. However, this disregards the Complainant’s Sweden trademark registration dated 2013, which therefore preceded by three years the Respondent’s registration of the disputed Domain Name. In view of this, and of the fact that the disputed Domain Name is identical to that 2013 trademark, the Panel declines to make a finding of Reverse Domain Name Hijacking.

Complaint Denied

Complainant’s Counsel: Patrade Legal ApS, Denmark

Respondent’s Counsel: Self-represented

Case Comment by ICA General Counsel, Zak Muscovitch: As I noted in my above comment on the EastmanMusic case, there are really three separate elements that are required to prove bad faith registration; firstly the Complainant must prove trademark rights which existed prior to the Domain Name registration; Then the Complainant must prove the Respondent’s awareness of its trademark at the time that the Domain Name was registered and this generally involves evidence of reputation; Finally, the Complainant must prove not just the Respondent’s awareness of the Complainant’s trademark, but also its intent to exploit the Complainant’s trademark, i.e. to target it.

Here, the Panel duly noted in connection with the first two aforementioned elements, that:

“It is incumbent on a complainant to come forward with evidence of the history, use and public profile of its trademark, including such matters as, e.g., geographical presence, revenues, promotional spend, industry recognition, and social media, in order to demonstrate that the respondent was likely to have been aware of its trademark.”

As the Panel noted however, the Complainant did not provide such evidence and the Panel’s own review of the Complainant’s website revealed that the earliest apparent use of the mark was in 2018.

The Panel in this case also made a helpful observation about privacy services which is similar to the observation made by the Panel in the EastmanMusic case, above:

“As registrars commonly provide a privacy or proxy service in connection with a domain name registration, the Panel does not consider the use of such a service to be in itself an indicator of bad faith. In this case, there is no evidence that the Respondent provided false contact details to the Registrar, and the Registrar promptly disclosed those details in connection with the proceeding.”

Right. When will Complainants cease making these spurious allegations and when will Panels finally lose all patience with them? I see little hope in the former and we are fortunately beginning to see the possible beginning of the latter.

Ankur Raheja is the Editor-in-Chief of the ICA’s new weekly UDRP Case Summary service. Ankur has practiced law in India since 2005 and has been practicing domain name law for over ten years, representing clients from all over the world in UDRP proceedings. He is the founder of Cylaw Solutions.

Ankur Raheja is the Editor-in-Chief of the ICA’s new weekly UDRP Case Summary service. Ankur has practiced law in India since 2005 and has been practicing domain name law for over ten years, representing clients from all over the world in UDRP proceedings. He is the founder of Cylaw Solutions.

He is an accredited panelist with ADNDRC (Hong Kong) and MFSD (Italy). Previously, Ankur worked as an Arbitrator/Panelist with .IN Registry for six years. In a advisory capacity, he has worked with NIXI/.IN Registry and Net4 India’s resolution professional.